The Council of Europe's Reaction to Russia's Aggression against Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine clearly demonstrates that the policy of the Council of Europe (CoE) up to now, based on leniency and appeasement towards the Russian government, was wrong. Suspension of Russia’s participation in the work of the main bodies, followed by its expulsion on 16 March, is a signal that gross violations of international law and human rights will no longer be tolerated. It is in the organisation’s interest to specify what it expects from Russia and to consistently refuse to normalise relations until its demands are met.

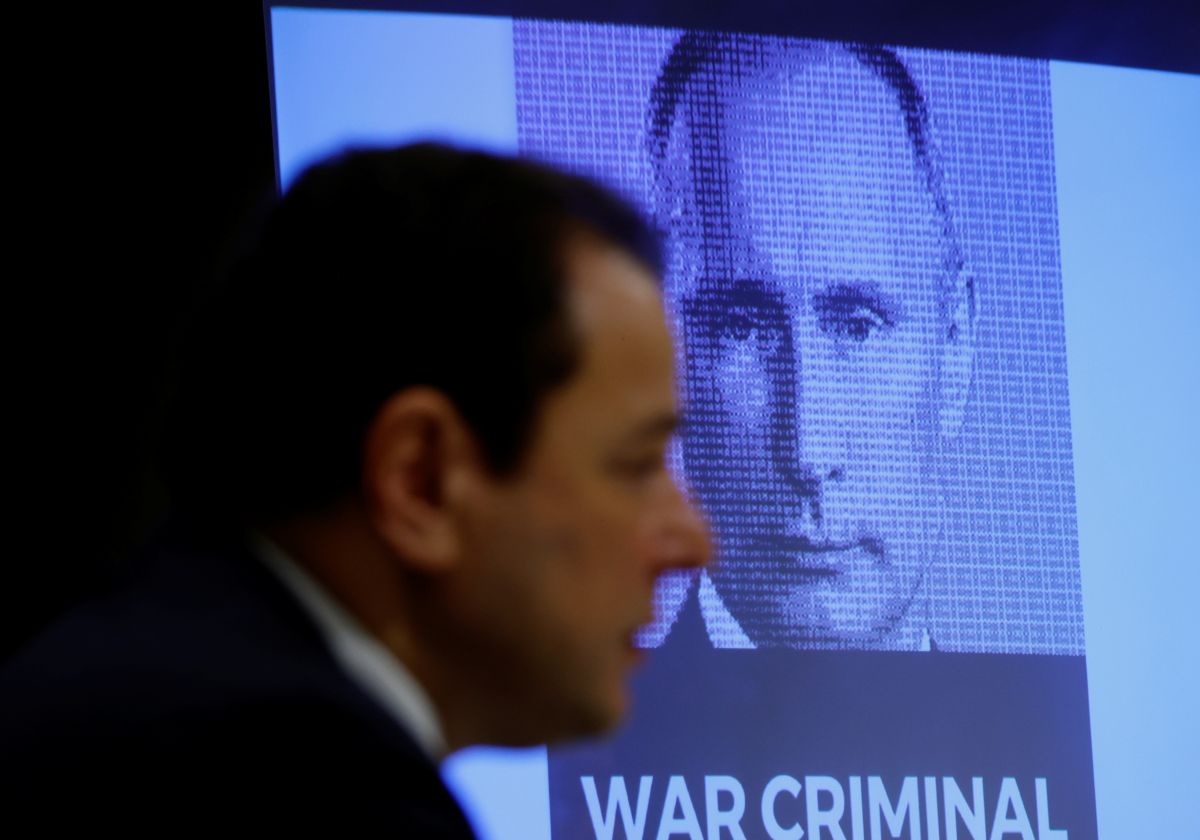

ARND WIEGMANN/ Reuters/ FORUM

ARND WIEGMANN/ Reuters/ FORUM

State of Play before the Invasion

Relations between the CoE and its member Russia seemingly improved in recent years. In July 2019, the organisation decided not to reapply the sanctions imposed on Russia after the annexation of Crimea and repealed provisions allowing their imposition. This occurred under the influence of Russia withholding payments to the CoE and threat that it would leave the organisation if it continued to restrict its rights. This was all the more surprising given that Russia failed to meet most of the demands addressed to it, such as annulling its annexation of Crimea and cessation of harassment against its population, the withdrawal of troops from Ukrainian territory, and an end to support for the self-proclaimed authorities in the occupied Donbas.

According to supporters of de-escalation, Russia’s continued membership was intended to allow the organisation to influence Russia more effectively and enable the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) to continue protecting victims of human rights violations in the country, including Russians themselves (without membership, this would have been impossible). Events since 2019 have shown that these expectations were illusory. Respect for democratic principles and human rights in Russia continued to deteriorate. The authorities impeded the exercise of freedom of association and expression by suppressing protests, restricting access to independent content on the internet, and interfering in the functioning of NGOs. Constitutional amendments in 2020 deepened the lack of independence of the judiciary and finally sanctioned the possibility of non-compliance with ECHR judgments, among other things. Persecution of the opposition continued, with the most publicised case being the attempted poisoning and later imprisonment of Alexei Navalny. Repression, electoral manipulation, and restrictions on media freedom also accompanied the September 2021 parliamentary elections. Russia also did not intend to implement the CoE’s expectations of improving the situation in the parts of Ukrainian territory under its control, and not only with regard to the withdrawal of troops but also to the treatment of the population. In the occupied part of Donbas, the death penalty was reinstated and torture and repression were used against political opponents and some religious communities. Violations of the rights of Crimean residents, especially Tatars, also intensified.

Aggression and Consequences

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February entailed further violations of basic norms of international law and human rights and created a humanitarian crisis. The authorities have also undertaken repression of Russians opposing the invasion, including mass arrests, suppression of protests, tightened censorship, and blocking access to the last independent media.

On the day of the invasion, the CoE’s Committee of Ministers condemned Russia’s armed assault on Ukraine as a serious violation of international law and its obligations under the Statute of the CoE, calling on it to halt the fighting. On 25 February, in consultation with the Parliamentary Assembly and at the request of Poland and Ukraine, it suspended Russia’s right to participate in the work of the Committee and the Assembly. In turn, the ECHR on 1 March, at the request of Ukraine, obliged Russia to cease its attacks on civilian populations and facilities under provisional measures (i.e., an order taken to safeguard the interests of victims of violations). On 8 March, Russia’s aggression and repression of Russians protesting against the war were condemned by the Secretary-General of the CoE and the presidents of the Committee of Ministers and the Parliamentary Assembly.

Russia nevertheless continued its military actions, and on 10 March its foreign ministry announced it would leave the organisation, accusing the “collective West” of imposing its own “rules” on Russia and destroying the “legal space in Europe”. Member states responded by entering into talks to strip Russia of its membership. Although the organisation’s statute provides for such a possibility, it would be a precedent in the more than 70-year history of the CoE and a major image blow (in the 1960s, Greece was threatened with such a move, but it left the organisation earlier on its own). Therefore, due to signals that there was a real chance of expulsion, on 15 March the Russian Federation notified its intention to withdraw from the Council of Europe. According to the statute of the organisation, however, it would remain a member until the end of 2022, and allowing it to leave voluntarily would be disproportionate to the scale of its transgressions. Therefore, on the same day, the Parliamentary Assembly issued a unanimous opinion that the gravity of Russia’s violations justified its removal from the organisation, and on 16 March the Committee of Ministers decided to do so immediately. As of that date, Russia ceased to be a member of the Council of Europe.

Consequences of Russia’s Loss of Membership in the CoE

Russia’s expulsion from the organisation means that about 7-8% of the CoE budget will have to be covered by its remaining members and that the CoE will have to dismiss staff who have only Russian nationality (the organisation requires staff have citizenship of one of its member states). There are still proceedings before the ECHR against Russia initiated by Georgia, Ukraine, and the Netherlands, as well as by nationals of CoE member states, including thousands of Russians—as of the end of February 2022, 25% of all cases before the ECHR were pending against Russia. According to Article 58 of the European Convention on Human Rights, despite its removal from the organisation, Russia will remain responsible for human rights violations it committed up to the time of the termination of its membership, so these cases will be able to continue. However, it is almost certain that Russia will refuse to enforce any judgments that may be unfavourable to it, such as payment for damages or ordered legislative changes (it also affects 2,000 judgments already considered by the ECHR as pending execution). In accordance with the ECHR's resolution of 22 March, it will still be possible to file new complaints regarding human rights violations committed before 16 September, but not after this date. New victims of the war in Ukraine or internal repressions in Russia will no longer be able to file complaints with this body.

Russia’s expulsion from the Council of Europe may result in increased persecution of Russian society and the last independent media. One element of this may be the reinstatement of the death penalty, (which is inadmissible in the Council and has not been applied in Russia since 1996) as already suggested by the deputy head of the Russian Security Council and former president, Dmitry Medvedev. By leaving the CoE, Russia will cease to be a party to the European Convention on Human Rights, but it is possible that it will also denounce some other treaties concluded within the CoE and available to non-members, such as the 1987 European Convention for the Prevention of Torture.

Conclusions

The restoration of Russia’s full rights in the ECHR in 2019, despite the failure to meet the vast majority of the demands addressed to it, was a mistake and created the perception among the Russian government that the organisation was willing to give way further in the name of maintaining unity and continuing the ECHR’s nominal protection of the rights of Russians. The actions taken since the 2022 invasion send a clear signal that flagrant violations will no longer be tolerated, restoring the organisation’s credibility. A further goal of the CoE should be to develop a list of demands for respect of fundamental legal principles expected from Russia and to make its readmission to the CoE or even future cooperation categorically conditional on their fulfilment. The minimum should be respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all CoE members and a clear improvement in the human rights situation in Russia itself.

Once Russia is removed from the CoE, the possibilities for the organisation to influence it will be slim, and the victims of violations by the Russian state apparatus will lose the ability to assert their rights before the ECHR. However, the same would also be the consequence of a voluntary departure. The lack of legal protection could be a factor in increasing the Russian public’s dissatisfaction with the authorities since it deprives victims even of the possibility of obtaining compensation. Ultimately, it will be the attitude of the Russians, affected also by sanctions, including those initiated by the EU and the U.S., that will determine any political changes and the possibility of their country ever returning to the CoE.

Poland may support CoE assistance for Ukraine, for example, in terms of documenting human rights violations by the office of the European Commissioner for Human Rights, and financing actions for the benefit of refugees and reconstruction of social infrastructure with the resources of the CoE Development Bank.