Circumstances

The Russian delegation was deprived of the right to vote in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) and to participate in the work of its subsidiary organs and in election monitoring missions in April 2014. This arose from Russia’s serious violation of the principles of the Council of Europe (CoE) in connection with the annexation of Crimea. Russia opposed the decision. In June 2017, it suspended payment of contributions to the organisation until the decision was repealed, and signalled its readiness to leave the CoE. In April 2019, it announced that it would depart if its delegates were not allowed to participate in the election of the new Secretary General (SG) and the judges of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), scheduled for 26 June. Under the CoE statute, July 2019 would mark the date from which Russia’s right to participate in the work of PACE and the second main CoE body, the Council of Ministers (CM), could be suspended due to a two-year delay in paying contributions. This would deprive it of influence on the organisation’s activities.

The incumbent SG, Thorbjørn Jagland, and some members of the organisation, particularly France and Germany, urged PACE to abolish sanctions. The CM also exerted pressure, calling on PACE on 17 May to ensure that delegations of all CoE members (including Russia) could take part in the PACE summer session between 24 and 28 June. However, the final decision on the status of the Russian delegation rested exclusively with PACE.

Restoration of Russia’s Rights

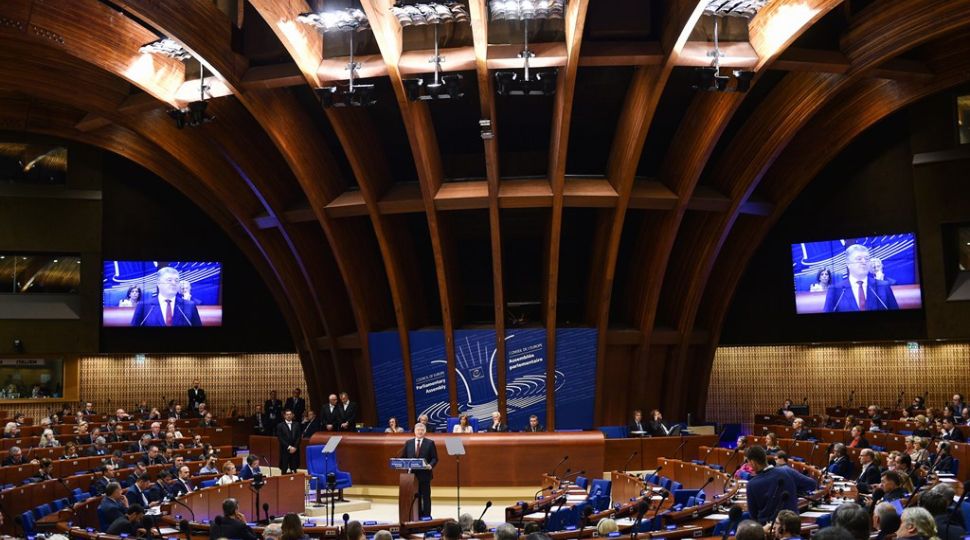

On 24 June, a vote took place on the resolution to remove from PACE rules of procedure the possibility of applying certain sanctions, including those imposed on Russia. The motion was supported by an overwhelming majority of delegates from France, Spain, Germany, Turkey, Italy and others. It was opposed mainly by representatives from Georgia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Sweden, Ukraine and the UK. In addition, PACE declared its intention to implement a joint response procedure (not yet fully developed) to replace the existing sanctions.

Russia tried to force further concessions. It nominated four people subject to EU and U.S. sanctions to its PACE delegation. One of them, Leonid Slutsky, was put forward for the post of one of the vice-presidents of PACE, a position customarily held by Russia. Slutsky’s candidature did not obtain the required number of votes. The position for which he was running will be vacant at least until the October session. PACE accepted the composition of the delegation, which means that people subject to sanctions will be able to travel in Europe enjoying PACE immunity. However, it demanded, inter alia, immediate payment of Russia’s overdue CoE contributions, and the release the Ukrainian seamen captured during the Kerch incident in November 2018.

Russia’s return to PACE allowed it to participate in the vote on the new SG. The outgoing one, Jagland, has been criticised by some human rights defenders and PACE members for his passiveness towards corruption in the organisation, his lenient approach to the purge in the Turkish state apparatus after the 2016 coup d’état attempt, and the pressure he exerted on lifting sanctions against Russia. Other The new candidates were the foreign ministers of Belgium (Didier Reynders) and Croatia (Marija Pejčinović Burić). Tensions caused by Russia’s return to PACE resulted in the Belgian candidate, considered to be pro-Russian, receiving much less support, and Ms Burić was elected as the new SG. She will assume her duties on 18 September.

Division in the Council of Europe

Russia’s return to PACE provoked different reactions of some CoE members. France and Germany were positive, claiming that the ongoing pan-European character of the organisation and the continued protection of Russian citizens in the ECtHR marked success. Russia also expressed approval, yet did not meet PACE demands about payment of its overdue contributions or the release of the Ukrainian seamen (also mandatory by order of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, dated 25 May).

Ukraine, which insisted on maintaining sanctions because of ongoing Russian aggression and occupation of part of its territory, recalled its representative at the CoE for consultations and withdrew the invitation for the CoE observers to observe elections on 21 July. Its delegation withdrew from further participation in PACE’s summer session and called on the Ukrainian president to consider whether the country should stay in the CoE. In a gesture of solidarity, the session was also left by delegates from Georgia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland and Slovakia. Together with the representatives of Ukraine, they issued a joint declaration stating that Russia’s return to PACE, despite its serious violations of CoE resolutions, was in conflict with the basic principles of the organisation and its statute. They announced that they would consider joint actions in PACE in the next sessions.

So far, only the Latvian parliament has commented on this matter. On 8 July, it declared that it would coordinate actions with the delegations of other states which voted against the restoration of Russia’s rights, but did not give further details. In mid-July, the foreign affairs committees of the Lithuanian and Estonian parliaments also dealt with the matter. There is no information on the outcome of the meetings, but the presidents of both committees were sceptical about boycotting PACE (called for by Georgian delegates), indicating that this would only strengthen Russia’s supporters. Some arrangements may be made on 6 September, at the meeting of the delegation of parliaments of the three Baltic States to PACE. The Polish lower house has not yet taken a position. There is little chance of Slovakian cooperation, as one delegate signed the declaration over the opinions of the others, who were against it but absent at the time.

Conclusions and Recommendations

PACE’s summer session was a success for Russia, which fully rejoined the CoE despite failing to act on demands set out in PACE’s resolutions. It was also able to block the re-imposition of sanctions. This would have required restoration of the previous wording of PACE rules of procedure, for which the required majority support vote is currently impossible, all the more so because PACE has just supported the creation of a new sanctioning procedure. As this procedure has not yet been developed, real sanctions have been replaced with potential ones. Russia also managed to sow discord between states opposing its return to PACE and those supporting it. Further actions aimed at destabilising the CoE can be expected, including attempts to force the CoE to recognise the annexation of Crimea by accepting PACE delegates nominated from this area.

Because Russia will remain in the CoE, its citizens will enjoy the protection of the ECtHR. However, representatives of some non-governmental organisations, including Memorial, argue that the CoE’s unilateral concessions towards Russia will in the long term damage human rights in that country.

Russia’s return to PACE, despite ongoing violations of the CoE statute, raises legitimate doubts as to the credibility of the organisation. It also threatens the future of other sanctions against Russia, such as those imposed by the EU. Therefore, it is advisable that the Polish delegation to PACE coordinate closely with those of other countries that opposed it. Withdrawal from the work of PACE, although important as a symbolic gesture, would indirectly benefit Russia. Therefore, it would be better to turn PACE’s attention to Russia’s failure to implement the resolution that allowed the return of its delegation, and then request that PACE limit the rights of Russian delegation in line with the revised PACE rules of procedure. The Russians may, for example, be prevented from tabling motions for resolution, submitting amendments, or sitting on most committees. A joint attempt to prevent the election of the Russian vice-president of PACE would also be desirable, particularly if someone subject to EU sanctions is nominated again. To deprive Russia of this function permanently would be much more difficult.