Likely Consequences of Council of Europe Concessions to Russia

Change of Approach and Premises

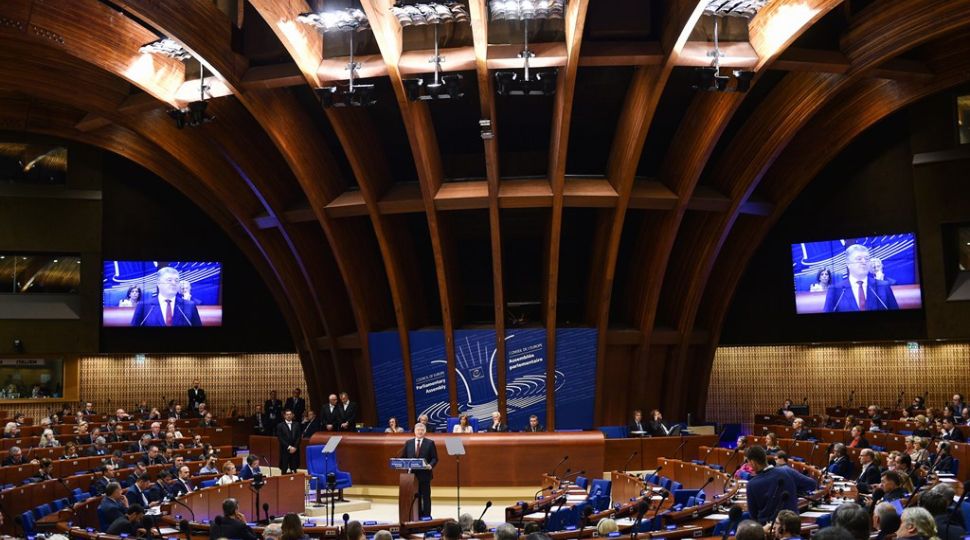

In October 2017, the Parliamentary Assembly (PA) of the CoE, an organisation that promotes the protection of human rights and democracy and which set in motion the process that led to the creation of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), adopted Resolution 2186 (2017). The solution initiated a process that could lead to the lifting of sanctions imposed on Russia after its annexation of Crimea in 2014. These include the suspension of the right of the Russian delegation to participate in the work of the PA (one of the Council’s two main bodies), its auxiliary bodies, and election-observation missions. A report on repeal of the sanctions is expected in mid-March. The decision whether to lift them may then come before the PA.

The resolution hinted at two reasons for such a step. These included Russia’s suspension of payments to the CoE since June 2017 until its delegation is fully and unconditionally allowed to participate in the works of the PA, and the PA’s aim to restore and strengthen CoE members’ sense of community before its jubilee summit in 2019. An additional argument was raised in statements by CoE Secretary General Thorbjørn Jagland at the end of 2017. He claimed that the pressure from the CoE may compel Russia to feel “forced to leave.” In his opinion, that would be a great loss both for Europe and the more than 140 million Russians who would be deprived of protection by the ECtHR.

Russia’s CoE Membership

Russia’s membership of the Council of Europe does not look good when it comes both to events within Russia as well as Russia’s international activities that have a wider impact on the protection of human rights in Europe.

Russia’s internal matters affected its admission to the CoE, which was suspended for more than half a year over serious human-rights violations in Chechnya. When admitted in 1996, Russia entered with a political deficit of trust. In 2000–2001, the actions of its organs during the Second Chechen War led to the suspension of the Russian delegation’s rights in the PA, based on the same rules as those pertaining to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Although over time the scale of the violations in Chechnya has decreased, respect for human rights in Russia still differs significantly from the European standard. It has become a rule that when the ECtHR finds a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Russia usually does not change the legislation or practices that violate the convention but only pays out compensation based on the award. Consequently, in 2017, it was estimated that it did not properly execute nearly 1,600 of more than 2,100 unfavourable ECtHR judgments. Moreover, in recent years, Russia has legally sanctioned the possibility of refusing to fulfil certain ECtHR judgments, declaring them incompatible with the Russian constitution. In July 2015, the Russian Constitutional Court supported such a practice, and in December 2015 this was implemented by legislation adopted by the Russian parliament. Based on this, Russia has refused to execute the judgment in Anchugov and Gladkov v. Russia of 2013, regarding Russia’s ban on the voting rights of all convicted prisoners serving prison sentences, and in Yukos v. Russia of 2014, ordering a payment of €1.9 billion in compensation to the shareholders of the Yukos group, which was essentially expropriated by the government. Although sometimes CoE members choose to postpone the implementation of ECtHR judgments, Russia is the first, and so far the only, country in Europe to systemically neglect such judgments, in violation of Art. 46 ECHR and the basic principles of the law of treaties. In a knock-on effect, Azerbaijan is currently considering whether to follow the Russian steps.

Externally, Russia’s military and political activities in the area of the former USSR have led to a gradual decline of the area of effective protection of human rights in Europe, or at least to a qualitative deterioration of such protection, starting from the early 1990s. Russian support has propped up the separatist regimes in Moldovan Transnistria and Georgian Abkhazia and South Ossetia. With the judgment in Ilaşcu and Others vs. Moldova and Russia in 2004, the ECtHR has started to hold Russia responsible for violations of the ECHR occurring in Transnistria and oblige Russia to pay compensation to the victims. A similar approach by the ECtHR may be expected in a coming judgment in proceedings initiated in 2008 in Georgia’s interstate complaint against Russia. Georgia argues that Russia bears responsibility for violations of the convention by the separatists in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Notable, Russia is the only member of the council to have taken actions supporting the separatist movements since submitting to ECtHR jurisdiction in 1998, specifically in Georgia in 2008and the annexation of Crimea and taking effective control over part of eastern Ukraine in 2014. Even if the tribunal finally allows inhabitants of these areas to pursue their claims directly against Russia—as in the case of Transnistria—such a solution will be far from perfect. In the legal doctrine it is considered desirable that individuals can effectively claim their rights before local courts, taking advantage of shorter, simpler, and less expensive procedures. This is not possible in the case of courts in these separatist areas because of doubts as to their compliance with basic procedural guarantees.

Conclusions

Russia has not reversed its annexation of Crimea and has failed to implement most of the calls in the resolutions relating to its activities in Ukraine. Consequently, the lifting of the sanctions imposed on it by the CoE could only seriously undermine the image of the organisation and the effectiveness of the sanctions system. What is more, abandoning sanctions in a situation in which the Russian government is trying to force changes beneficial to it by refusing payments to CoE, would mean giving in to coercion. It would undermine trust in the CoE in many European countries, especially in Ukraine, but also in Georgia and Moldova. The Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the CoE, Dmytro Kuleba, has stated several times that his country would review its relations with the council if that happened.

Calls to allow the Russian delegation to participate in the meetings of the PA demonstrate a misunderstanding of the real essence of international sanctions, particularly those without economic character. The inconvenience the latter cause—if observed—increases, rather than diminishes over time and make it impossible to normalise a seemingly stable situation. The growing criticism of European states of Ukraine’s authorities is conducive to Russia in this respect and is a reason why Russia is trying to lift the sanctions now. It is also why the council cannot give them up.

Russia’s internal and external activity in the area of human-rights protection deviates more and more clearly from the CoE standards. Therefore, the unconditional restoration of the right of the Russian delegation to participate in the work of the PA can only lead to confusion as to the real goals and values of the organisation and raise doubts about its determination to defend them. The view that allowing the Russian delegation to return will lead to the restoration of a sense of a community of values among CoE members is wishful thinking.

If Russia really decides to leave the CoE, so far ruled out by some high-ranking Russian politicians, including Valentina Matviyenko, chairman of the Federation Council, that would only confirm how far it has moved away in terms of democratic standards and human rights from the rest of Europe. The benefits of Russia “staying in Europe” and continued protection of its citizens by the ECtHR, as indicated by Jagland, are real as long as Russia at least tries to comply with the principles respected by the other CoE members.

The PA may decide to lift the sanctions by a simple majority. The voting on Resolution 2186 (2017) revealed that apart from Ukraine’s PA members, such a move would likely be opposed almost exclusively by the delegates from Poland, Georgia, and the Baltic and Scandinavian states. That is why Polish PA parliamentarians should consider cooperation with delegations of states that support maintaining the sanctions, articulating the threats posed by a change of position in the Council of Europe.