Legal Aspects of the Attack on Ukraine

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, carried out with the support of Belarus, is a violation of the norms of international law that form the basis of the international order shaped after the Second World War. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s justifications of the attack are legally questionable and contradictory to facts. There are also violations of humanitarian law being committed in the course of the hostilities, especially concerning the protection of civilians. The aim of the international community should be to stop the aggression and hold accountable states and individuals responsible for these violations.

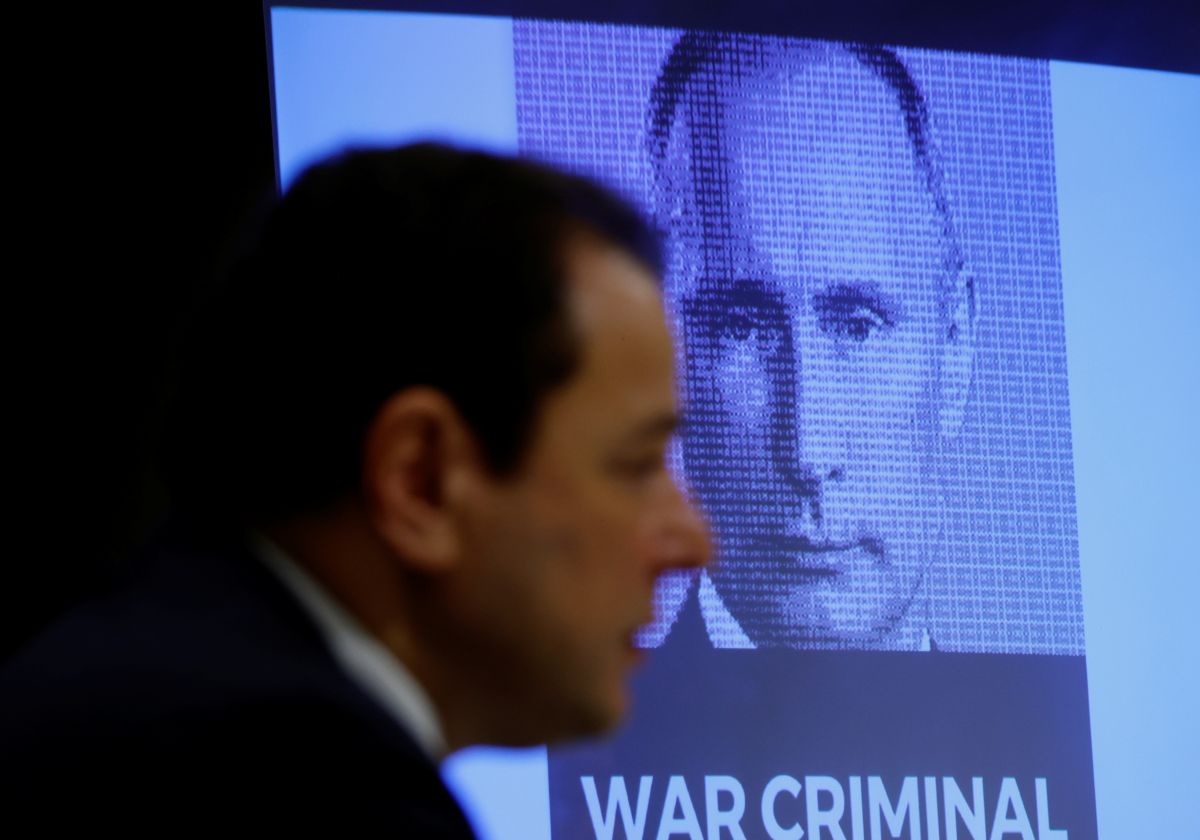

Foto: KIM KYUNG-HOON / Reuters / Forum

Foto: KIM KYUNG-HOON / Reuters / Forum

How should Russia’s attack and Belarus’s support be assessed from the perspective of international law?

Russia’s armed attack is a use of force against the territorial integrity and political independence of another state, contrary to Article 2(4) of the Charter of the United Nations and entitling Ukraine to self-defence under Article 51 of the Charter. It is an act that contradicts the principles of the Statute of the Council of Europe and the obligations expressed in the CSCE Final Act, the Charter of Paris for a New Europe, and the Budapest Memorandum. In light of the judgments of international tribunals and UN General Assembly Resolution 3314 of 1974, which reflects customary law, actions including bombing, attacks on armed forces, invasion, military occupation, and support for separatist attacks must also be described as aggression. Any territorial acquisitions obtained as a result would be contrary to customary international law, such as the case of Iraq’s attack on Kuwait in 1990, and recognition of these acquisitions by other states would violate international law.

Although the troops of Belarus, according to a statement by Alexander Lukashenka, are not involved in the armed attack on Ukraine, it is an aggressor state as well. Resolution 3314 clearly indicates that aggression includes making one’s territory available to another country to commit an act of aggression against a third country.

Why does the Russian justification for the attack not provide a legal basis for the attack?

In his speech on 24 February, Putin tried to justify the attack primarily on the basis of the need for preventive collective self-defence of the so-called “People’s Republics” (DNR/LNR) against an alleged attack by Ukraine and NATO. The legality of such self-defence is controversial in international law. Ukraine has for years sought to regain Crimea and parts of Donbas by peaceful means, including through negotiations and proceedings before international tribunals. NATO is a defensive alliance and has been strengthening its capabilities in Eastern Europe over fears of Russia’s increasing aggressiveness, which the attack on Ukraine has just confirmed. Moreover, the “people’s republics”, entities not recognised by any state other than Russia, were not entitled under international law to ask for assistance in self-defence. Putin also invoked the need to stop what he termed “genocide” committed by Ukraine in Donbas, which is a claim not supported by any credible source, such as reports from international human rights organisations.

Can Russia and Belarus be held accountable and how?

According to judgments of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), including the February 2022 verdict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda, aggression gives rise to international responsibility towards the victim state and results in the obligation to pay reparations. However, holding Russia and Belarus responsible for it will be impossible as they have not consented to ICJ jurisdiction. On the other hand, Ukraine will be able to bring Russia before the ICJ based on conventions containing an automatic consent clause, such as those on combating the financing of terrorism (for supporting separatists) and eliminating all forms of racial discrimination (for violations based on national origin). It will also be able (as will its citizens) to claim compensation from Russia, for example, for damage to private property or civilian casualties, before the European Court of Human Rights. However, enforcement of a ruling will likely be fraught with difficulties due to Russia’s probable resistance.

What is the assessment of the ongoing armed actions from the point of view of humanitarian law?

The armed conflict caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine is an international conflict to which the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1977 First Additional Protocol apply. Media reports indicate, among others, cases of bombing or rocket attacks on civilian settlements and hospitals, resulting in deaths or serious injuries of defenceless civilians, and large-scale destruction of property. Such actions are contrary to the Fourth Geneva Convention and the First Protocol. As such, they may be defined as war crimes and, depending on their scale, the intent of the perpetrators, and other factors, they may take the form of crimes against humanity or even be legally qualified as genocide. Verification of information on violations could be carried out by, for example, a specially appointed UN rapporteur or an EU fact-finding mission, although with the continuation of the Russian attacks, probable occupation, and a lack of Russia’s consent to monitor their activities, the room for action will be limited.

How can the perpetrators of violations of humanitarian law be held accountable?

Although perpetrators of crimes of aggression can be tried by the International Criminal Court (ICC), this will not be possible for Putin, Lukashenka, or their subordinates in the current situation. The Rome Statute establishing the ICC excludes this possibility for states that are not parties to it, and Belarus, Russia and Ukraine have not ratified it. These people could, however, be held accountable before the ICC for war crimes, and potentially for crimes against humanity or even genocide on the basis of Ukraine’s 2015 declaration to recognise the ICC’s jurisdiction. It is also possible in countries allowing a legal feature called “universal jurisdiction”, with is the trial of criminals by national courts. Such steps were taken, for example, by the UK and Spain against former Chilean President Augusto Pinochet in the 1990s, and more recently by Germany and Sweden against suspected criminals in Syria. Both in the case of the ICC and national courts, however, the challenge is to apprehend the perpetrators, which requires their arrest while on the territory of a state party to the statute.