China Makes Subtle Adjustments to Its Ukraine Policy

Although China has maintained a pro-Russian position since Russia’s invasion in February 2022, subtle adjustments to its policy towards Ukraine have emerged in recent months. These include intensified bilateral cooperation at lower levels, and the new Chinese ambassador in Kyiv has increased his engagement with Ukrainian businesses, academia, and the administration. These changes may suggest that China is preparing for potential involvement in Ukraine’s reconstruction after a ceasefire or peace declaration. However, they do not signify a change in China’s position on the war or Russia itself.

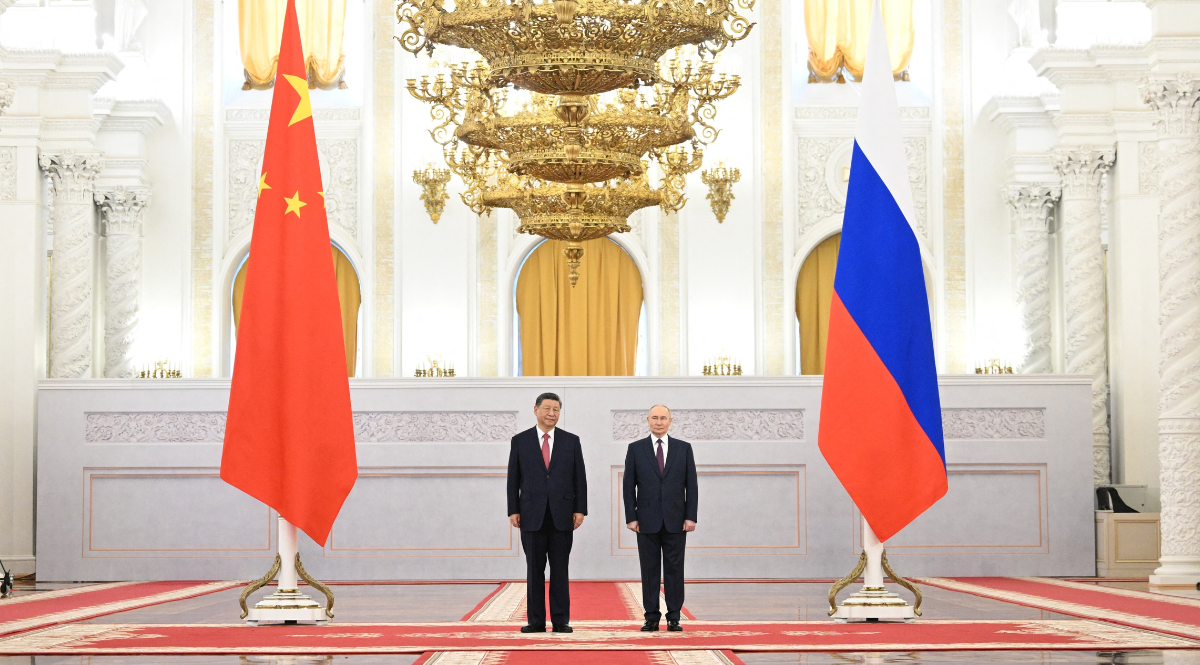

AA/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

AA/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

China’s Stance on Ukraine

From the annexation of Crimea in 2014 to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, China did not support Ukraine. While officially declaring its neutrality in 2014, China emphasised its respect for Ukraine’s territorial integrity (as stated by then Prime Minister Li Keqiang). This signalled to Russia that China did not fully accept its actions. Nevertheless, China’s neutrality bore the hallmarks of pro-Russian sentiment, as evidenced by statements from Chinese authorities. These included calls for the rights of all national minorities in Ukraine to be respected, which could be interpreted as a reference to Russians living in Crimea. There were also frequent references to the idea that “the current situation had specific causes”, which could be seen as an allusion to the alleged involvement of Western countries that provoked Russia.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, China’s approach to the country has changed significantly. It is now clearly pro-Russian, with China avoiding high-level contact with Ukrainian representatives. Since February 2022, Chinese President Xi Jinping has only spoken with President Volodymyr Zelensky once, in a telephone conversation in April 2023. This was most likely the result of international pressure on China, which, despite calling for a diplomatic resolution to the conflict, did not engage in any direct dialogue with Zelensky. During this time, Xi has spoken with and met Putin on numerous occasions, including during official visits. In 2025 alone, the two leaders have spoken several times, with Xi visiting Moscow in May and Putin expected to visit China in September to attend the celebrations marking the end of World War II in Asia.

The Chinese authorities consistently refer to the situation as the “Ukrainian crisis”, rather than a “war”, suggesting that NATO and the U.S. are responsible for ignoring Russia’s security concerns. This points to the need to change the security architecture in Europe and is consistent with Russia’s narrative and strategic objectives. They do not declare respect for Ukraine’s territorial integrity in their statements, which is a change compared to 2014, and they also avoid using the country’s name (references to Ukraine are adjectival in nature). This signals that they do not treat Ukraine as a fully sovereign state, but as part of Russia’s sphere of influence. Similarly, in the two proposals for a political solution to the “Ukrainian crisis” signed by China—the first in February 2023 and the second in April 2024, presented together with Brazil—Ukraine was not explicitly identified as a victim of Russia’s armed aggression.

Subtle Signs of Change

Although China’s position on the war and its support for Russia has not changed, subtle adjustments to China’s approach to Ukraine have been noticeable in recent months, especially since Donald Trump took office as U.S. president in January this year. This has consisted of intensifying cooperation at lower levels without publicising information about such activities.

For example, two agreements concerning the export of Ukrainian agricultural products (peas, fish and seafood from natural fisheries) to China were signed in early March this year. The agreements will remain in force for five years. Although these may seem insignificant, they are in fact very important because China is Ukraine’s largest trading partner and one of the world’s largest importers of agricultural and food products. According to the Ukrainian Minister of Agriculture Vitaliy Koval, the deals will increase export revenues and contribute to their diversification, strengthening Ukraine’s position as a reliable supplier of high-quality food products. Given the importance of food security in China—a de facto political issue—the agreements could increase Ukraine’s position in Chinese politics.

In November 2024, China appointed Ma Shengkun as its new ambassador to Ukraine. He is the former deputy director-general of the Arms Control Department at the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Ma has also previously worked in the International Department of the Central Committee (a party institution considered more important than the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and at the Chinese Mission to the United Nations in Geneva. In contrast to his predecessor Fan Xianrong, Ma is an active ambassador with more diplomatic experience. Before he was based in Kyiv, Fan mainly served in Chinese missions in Russia, including as counsellor at the embassy in Moscow and consul at the consulate in Khabarovsk. Since taking office, Ma has been actively developing contacts with the Ukrainian administration, businesses, and experts. Information about meetings with Ukrainian representatives posted on the website of the Chinese embassy in Kyiv demonstrates his significantly greater activity compared to his predecessor. At the same time, neither side is particularly highlighting this activity. This is most likely a deliberate move, calculated not to provoke Russia. In June, Ma was among more than 60 diplomats who visited the site of the Russian missile strike the Solomianskyi District of Kyiv.

China has suggested the possibility of participating in a peacekeeping mission in Ukraine. Evidence of this includes statements from officials indicating that it is still too early to discuss the matter, as well as the first visit to Europe (France and Germany) by Chinese Defence Minister Dong Jun in four years, which took place in May this year. During this visit, he participated in a UN conference on peacekeeping missions. Chinese experts (and officials as well) are also discussing China’s potential involvement in such a mission, emphasising that it would require a mandate from the UN Security Council.

Conclusions

Since Trump returned to power in the U.S. and took his first steps to end the war, changes in China’s policy towards Ukraine have become more apparent. These adjustments suggest that the closer the conflict is to being frozen, the greater China’s interest is in becoming involved in Ukraine. However, this does not indicate a shift in China’s stance on the war in Ukraine or its pro-Russian position.

From China’s perspective, the most effective way to stop military action would be to freeze the conflict—essentially, a “hybrid peace”, where Russia is neither victorious nor defeated. If Russia were to emerge victorious, it would gain significant political strength on a global level, not just in Europe, which could threaten China’s interests. Conversely, a decisive Russian defeat could lead to instability in the immediate vicinity of China. Furthermore, a Russian defeat would likely result in a change of leadership. Even if the new leader were authoritarian, this would introduce uncertainty into Sino-Russian relations, as establishing relations with them would take time.

These adjustments suggest that China is preparing for a more significant role in Ukraine following a ceasefire and the freezing of the conflict. China’s interest in participating in Ukraine’s reconstruction is evident in the twelfth and final point of the peace plan announced by China in February 2023, a year after Russia’s invasion. According to the plan, “the international community should take action to support post-war reconstruction in conflict-affected areas. China is ready to provide assistance and play a constructive role in this regard”.

China will treat any involvement in Ukraine strictly utilitarianly, with the aim of expanding its political and economic influence in Europe to its own advantage. China’s involvement could take two forms: it could send a small number of police officers or engineering troops as a symbolic peacekeeping force, or it could participate in the reconstruction of Ukraine. Participation in a peacekeeping operation could be a preparatory phase for reconstruction involvement. Under the banner of reconstruction, China would likely be interested in acquiring raw material deposits and investing in infrastructure and energy. It is also possible that China would seek to cooperate in acquiring Ukrainian military technology.

Given the enormous scale of Ukraine’s reconstruction needs, the sooner China gets involved, the greater its chances of securing lucrative contracts and strengthening its political position in Europe. This would present a significant challenge to the EU. In order to curb China’s growing presence in the EU’s immediate neighbourhood, the EU must support Ukraine in winning the war, develop a European plan for Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction, and accelerate Ukraine’s accession process to the European Union.

(1).png)