American-British Trade and Technology Partnership: Implications for Poland and the European Union

The Economic Prosperity Deal (EPD) and Technology Prosperity Deal (TPD), signed between the United States and the United Kingdom in 2025, mark a new stage in their “special relationship.” The documents define the United Kingdom as the United States’ closest partner in the field of innovation and recognise the joint goal of shaping global standards in artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, nuclear energy and strengthening the American-British technological bloc. Although this may limit the EU’s influence on global technological processes, it also creates an opportunity for integration with new supply chains and closer cooperation in the fields of security and energy. It is in Poland’s interest to strengthen EU-UK-US cooperation, which could bring benefits in defence, energy and cyber innovation.

TNS/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

TNS/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

The political and economic changes following Brexit provide key context for the current partnership between the US and the UK. Between 2019 and 2024, attempts to conclude a free trade agreement between the two countries were unsuccessful. Joe Biden’s administration was sceptical about Brexit, prioritising relations with the EU. In turn, Donald Trump’s first administration (2017–2021) saw an agreement with the UK as a potential model for future bilateral agreements outside the EU structures, but lacked internal political support to conclude it before the end of his term in 2020.

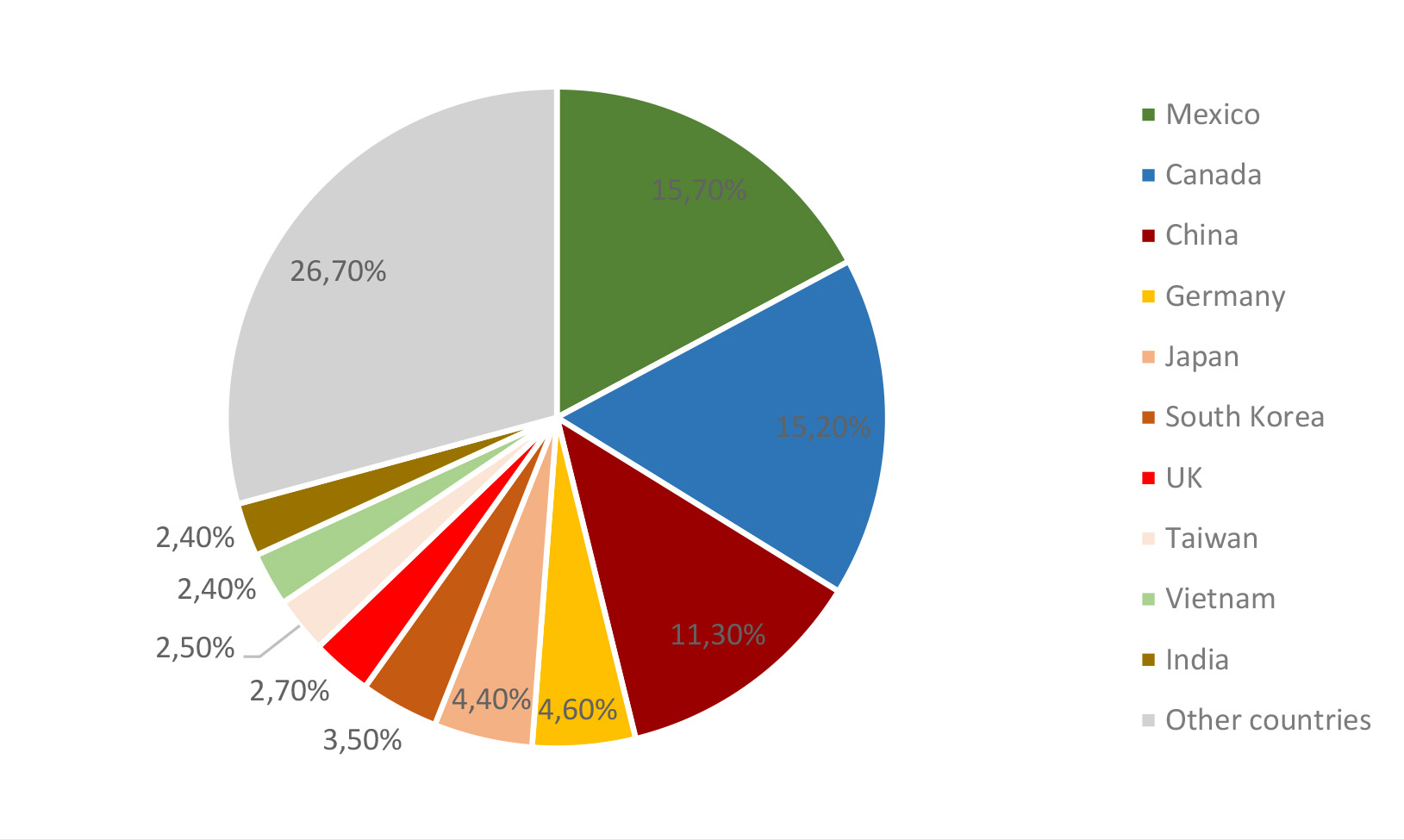

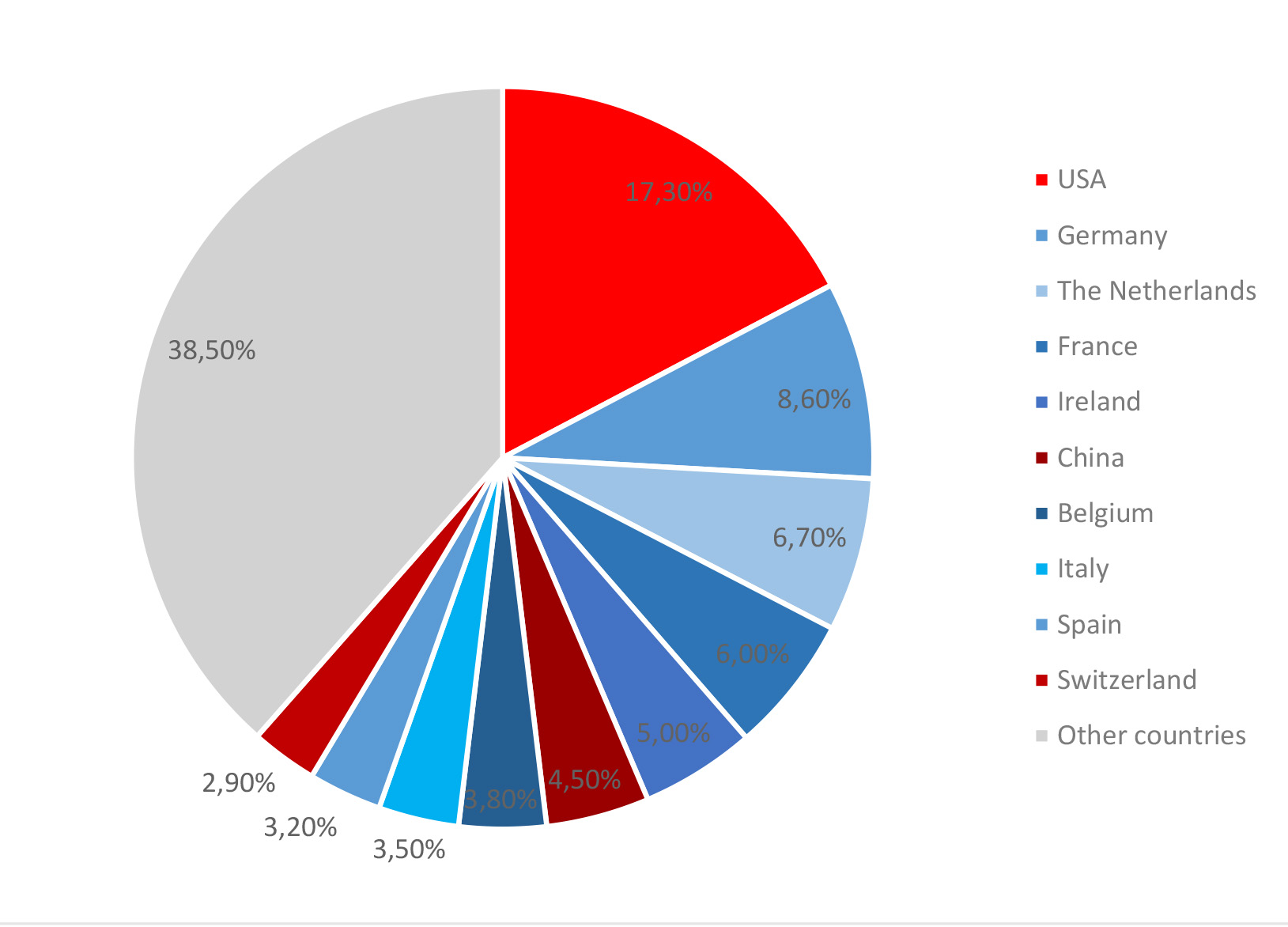

The basis for the current renewed partnership is intensive trade, the scale of which makes it strategically important for both sides. According to data from the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR), in 2024, the total value of trade between the US and UK amounted to $340.1 billion, including $147.7 billion in trade in goods. US exports to the UK reached $178.9 billion, while imports from the UK amounted to $161.2 billion, making the UK one of the leading trading partners with which the US has a positive balance of trade in goods (see Table 1). In 2024, the US was the UK’s largest trading partner (17.3% of total foreign trade), ahead of Germany (8.6%) but behind the European Union as a whole (41%). At the same time, the United Kingdom ranked 9th among US trading partners in goods trade, 1st in services trade and 7th in terms of total trade value (see Charts 1-2).

New Framework for Economic and Technological Cooperation

Signed on 8 May 2025, the Economic Prosperity Deal (EPD) creates a political framework, requiring further refinement into a legally binding form. It introduces asymmetric tariff adjustments: US tariffs on British exports average around 10%, while the UK has reduced tariffs on US goods to around 4%. The agreement introduces preferences in the automotive and aviation sectors and strengthens the mutual recognition of technical standards and approvals. It also restricts the re-export of goods of Chinese origin, strengthening the process of decoupling from China. The agreement remains balanced nonetheless. For instance, it was crucial for the UK to reduce customs duties from 25% to 10% on a quota of 100,000 cars, which allowed it to save 150,000 jobs in the British automotive industry. The UK also maintained its sanitary and technical standards, which, among other things, limit the imports of American foodstuffs. Trump, on the other hand, politically used the EPD as the first trade agreement of his second term to demonstrate the effectiveness of his trade policy.

The aim of the Technology Prosperity Agreement (TPD) of 18 September 2025 is to strengthen cooperation in strategic technology sectors, including artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, nuclear energy (including nuclear fusion and advanced modular reactors—AMR), as well as supply chain security and the creation of well-paid industry jobs. The agreement is again a politi cal framework (not a treaty) and is based on a balanced exchange of benefits. The TPD commits both governments to coordinating investment controls, supporting innovation clusters and developing common standards for security and nuclear non-proliferation. It also introduces a permanent institutional dialogue on technology development between US and UK agencies and aims to facilitate cooperation between universities, companies and start-ups, particularly in the defence sector, making innovation a central element of bilateral relations. Under the TPD, the UK is to receive £31 billion in US investment in data centres and regional AI growth zones (see Table 2). On the day the TPD was signed, the Starmer government also signed a £1.5 billion agreement with the US company Palantir to implement in the British Army’s command systems AI-based software tools tested during the war in Ukraine.

The US and its Partnership with the UK

he EPD and TPD serve to redefine bilateral relations with the UK. The second Trump administration is limiting multilateral cooperation in favour of transactional and sectoral agreements designed to attract innovation, secure supply chains and counter Chinese influence by incorporating allies into US regulatory and investment networks. This strategy is linked to an artificial intelligence development plan that involves exporting integrated technology packages to key partners in order to maintain US global leadership in this field.

Thanks to its traditionally close relations with the US, the UK has gained priority access to the US market as a “trusted partner” of the Trump administration, supporting the American industrial and technological base. The asymmetric reduction of tariffs under the EPD, agreed to by the British side, while maintaining higher US rates, is intended to confirm the effectiveness of Trump’s trade policy, in which customs instruments have become a tool of political pressure. Under the EPD, the administration has announced the removal of 25% tariffs on British steel in order to diversify supplies of this raw material to the US market on even more favourable terms than for other partners (subject to 50% tariffs), while maintaining protection for domestic industry.

The strengthening of relations with the United Kingdom also includes continued cooperation in the field of security. Both countries share a similar view of the main threats, although the Trump administration is adjusting Biden’s expectations of the United Kingdom, which are in line with the concept of “Global Britain.” Contrary to the previous approach, Trump has pointed to the need to concentrate British military resources in the Euro-Atlantic area at the expense of their presence in the Indo-Pacific. The US Department of War clearly separates these two theatres of operation, pressing for increased defence spending by NATO allies and greater responsibility for their own security. In this context, the UK’s capabilities would primarily strengthen the European pillar of the Alliance, especially in terms of deterring Russia and supporting Ukraine.

For the Trump administration, technology and innovation also set a new framework for cooperation in the field of intelligence. An example is Google’s £542 million investment in cloud technology in the UK, which is intended to strengthen cooperation between the intelligence services of both countries. At the same time, Trump’s distrust of the intelligence community, already evident during his first term, is leading to changes in the functioning of US agencies within the American s ystem and in relations with allies, among which the Five Eyes alliance (US, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) plays a key role. Given that in April 2025 the US suspended the exchange of information with its partners on Ukraine’s peace negotiations with Russia, and Trump even considered excluding Canada from this format, the TPD should re-establish the basis for particularly close US-British cooperation.

The UK and its Partnership with the US

From the UK’s perspective, the new agreements are not only intended to compensate for the losses in trade with the European Union after Brexit, but also to link the British economy to one of the two global centres of key technology development, alongside China. As a result, the EPD and, in particular, the TPD would significantly improve the UK’s economic competitiveness compared to the EU and symbolically confirm the “special relationship” between the UK and the US, which is based on trade, technology, defence and security interdependence.

The new partnership is linked to US investments in the UK in the fields of AI, quantum computing and clean energy. It is accompanied by a US investment plan worth approximately $350 billion, under which companies such as Microsoft, Lockheed Martin and Westinghouse will expa nd their research and development activities in the UK. This influx of investment could enable the UK to realise its ambition of becoming a scientific and technological superpower by 2030. At the same time, the TPD is increasing pressure on the Starmer government to ensure stable and cheap energy supplies and to align British climate policy with the industrial priorities of the Trump administration, including the launch of domestic shale gas and oil production and the withdrawal from some climate regulations. Long-term energy security and an increase in the export potential of the British technology sector are to be guaranteed by the development of nuclear energy, especially based on nuclear fusion and AMR technologies.

The TPD also supports the objectives of the Strategic Defence Review (SDR) of June 2025, which assumes that innovation will become the foundation of national security. Research in the fields of defence, cyber defence and artificial intelligence forms the basis for new operational doctrines and procurement plans. An example of this is the aforementioned Ministry of Defence contract with Palantir for a digital command system. Another pillar of this approach is combining defence innovation with civilian innovation and maintaining the UK's position as a leading European hub for military technology start-ups, while ensuring interoperability with US systems.

Prospects for the Implementation of the New Partnership and its Impact on the EU

The EPD and TPD have the potential to become a renewed foundation for the “special relationship” between the US and UK, but their durability will depend on the implementation capabilities and stable cooperation of both countries despite the high dynamics of their domestic policies (in particular, high political polarisation in the US and rapid growth in support for the populist right-wing Reform Party in the UK at the expense of both Labour and the Tories). Full implementation of both agreements could fundamentally transform the basic assumptions of UK regulatory policy, shifting it from the EU’s cautious model towards the American model based on calc ulated risk. Such a change would consequently also redefine economic relations between the UK and the EU due to competitive pressure on the Union.

The implementation of the EPD and TPD could significantly affect the relations set out in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). Although the British-EU agreements of May 2025 declared maintaining a stable and constructive partnership, in practice, the British government is shifting the focus of its economic diplomacy towards the US. During the UK-EU summit in May 2025, both sides announced regulatory cooperation on artificial intelligence, data and energy, but the conclusion of the EPD and TPD may reduce the UK’s motivation to deepen ties with the EU. This is because the US-UK framework provides faster regulatory processes, access to venture capital and a more flexible approach to export controls, i.e., benefits that the EU cannot easily offer.

This creates a strategic dilemma for the EU: how to maintain the cohesion of the pan-European innovation market while engaging the UK in cooperation with the US. Growing differences in standards, particularly in the areas of security and artificial intelligence, quantum technologies and nuclear licensing, may hamper data flows and scientific cooperation. However, the review of the TCA

and the development of the EU-UK strategic partnership, scheduled for 2026, may allow for the development of a parallel alignment mechanism: the functioning of two separate but interoperable regulatory systems enabling deeper cooperation after Brexit.

The UK’s relations with key European partners will also be increasingly determined by the technological agenda and the way in which France, Germany (as the other members of the informal E3 group, alongside Britain), as well as Poland and Ukraine, cooperate with the United States.

When it comes to the E3, British-French relations are characterised by both competition and cooperation. Both countries recognise the strategic value of their nuclear and defence sectors, and the Lancaster House treaties remain the basis for joint projects. At the same time, France maintains strong military-technological cooperation with the US, although it consistently defends the concept of European strategic autonomy. The strengthening of British-American cooperation in nuclear energy and artificial intelligence research is likely to weaken British-French ties. The UK and the US have a similar, more flexible approach to AI standards and nuclear sector regulation than that prevailing in the EU, which may raise concerns in France, although common challenges from China favour coordination between these three countries within NATO or the European Political Community. The American-British regulatory philosophy focuses on standards developed by public authorities in cooperation with economic operators, a more flexible approach to risk assessment (especially regarding AI), and the rapid adaptation of the legal framework to the current state of innovation, including testing the legal framework for technologies in so-called “regulatory sandboxes,” i.e., legal structures that allow economic operators to operate in a safe testing environment in order to experiment with a given project or service under relaxed rules.

British-German relations are dominated by their economic dimension. German industry can indirectly benefit from the dynamism of the British technology sector through investment links. The Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, signed in October 2025, signals the interest of both countries in easing technological competition through joint projects in the field of dual-use technologies and supply chain resilience. From the US perspective, both countries are important manufacturing and research centres in Europe, but the Trump administration prioritises cooperation with the UK, while expecting Germany to increase its defence spending, a situation which may create tensions in the US-UK-Germany triangle.

The US and the UK remain Ukraine’s key security partners, providing advanced drone systems, cyber solutions and military training. At the same time, they benefit from Ukraine’s war experience. Both the US and the UK see Ukraine as a key area for testing and implementing military innovations, particularly in the field of AI and unmanned systems. In the logic of the TPD, the inclusion of selected Ukrainian entities in US-British arms supply chains would be a natural development of existing cooperation. In such a scenario, Poland could act as a logistical and industrial partner. This would enable the creation of a trilateral Polish-British-Ukrainian agreement in line with US interests and strengthening NATO’s eastern flank.

If the US-UK technological axis continues to strengthen, it will have a positive impact on NATO’s innovation ecosystem, while limiting Europe's autonomy in shaping technological standards that are key to the future economy. Closer cooperation between the UK and the US within regulatory coalitions will reduce the EU's influence in international forums such as the OECD (AI group) and the International Atomic Energy Agency. However, selective convergence is possible, as the EU-UK agreements of May 2025 include elements of mutual recognition in the areas of cybersecurity and AI risk assessment.

Recommendations for the EU and Poland

The European Union could use the 2026 TCA review to deepen its dialogue with the UK on innovation and create a permanent forum for cooperation on standards in artificial intelligence, nuclear energy and cybersecurity. It is also necessary to accelerate the implementation of AI and quantum technologies in industry and to support public-private demonstration projects competing with US-UK initiatives. The EU should expand its cooperation with the UK in the field of nuclear fusion and AMR, including the development of joint pilot programmes under Euratom and ITER, in order to reduce the risk of technological dependence on the Anglo-American model.

It is important to integrate defence innovation policy with NATO initiatives and to coordinate the European Defence Fund with the NATO Innovation Fund and the DIANA accelerator. The EU should leverage the UK’s cooperation with Germany and Poland to create industrial anchors linking EU supply chains to the UK market. The integrity of the single market should be protected while remaining open to strategic partnerships, including through flexible regulatory clauses allowing UK entities to participate in selected EU research projects.

Poland can use the US-UK partnership to strengthen its own technological base, including by engaging in trilateral projects based on existing defence programmes such as Narew and Miecznik naval modernisation plans. It is worth initiating a US-UK-Poland dialogue on defence innovation, focusing on the use of AI in command systems, cybersecurity and energy, and ensuring technology transfer through appropriate offset clauses.

Poland should increase its participation in consortia involved in nuclear fusion and AMR, including Polish research institutes and energy companies in European and British pilot programmes. It is important to create synergies between EU and NATO innovation instruments, including by directing part of national funds to projects eligible for both EDF and DIANA. Production cooperation with the UK and Ukraine in the fields of drones, cybersecurity and AI-based logistics should also be a priority, as this would enable the development of a resilient regional ecosystem.

On the European stage, Poland can engage in active dialogue with France and Germany, acting as a mediator between the EU and Anglo-American approaches to technology regulation, promoting interoperability rather than competitive fragmentation.

Chart 1. The United States’ largest partners in goods and services trade (data for 2024, % of trade turnover)

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the US Census Bureau—Foreign Trade Division.

Chart 2. The United Kingdom's largest partners in goods and services trade (data for 2024, % of trade turnover)

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the Office for National Statistics.

Table 1. Bilateral trade between the United Kingdom and the United States in 2024

|

Trade category |

Values reported by the United Kingdom (converted to US dollars) |

Values reported by the US (US dollars) |

Difference between UK and US data (US dollars) |

|

Exports of goods from the United Kingdom to the US |

75.3 billion |

68.2 billion |

+7.1 billion |

|

Exports of goods from the US to the UK |

72.5 billion |

79.5 billion USD |

–7.0 billion |

|

Total trade in goods |

147.8 billion |

147.7 billion |

≈0 |

|

Exports of services from the UK to the US |

174.0 billion |

93.0 billion |

+81.0 billion |

|

Exports of services from the US to the UK |

77.7 billion |

99.4 billion |

–21.7 billion |

|

Total trade in services |

251.7 billion |

192.4 billion |

+59.3 billion |

|

Total trade |

399.5 billion |

340.1 billion |

+59.3 billion |

Sources:

Department for Business and Trade (DBT), United States – Trade and Investment Factsheet (31 October 2025), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/69135e9a5dec0071ce4963e5/united-states-trade-and-investment-factsheet-2025-10-31.pdf

United States Trade Representative (USTR), United Kingdom – Country Page, data for 2024, https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/europe/united-kingdom

Conversion rate: £1 = $1.27

Notes: The difference in data reporting for trade in services (approx. 15%) is due to differences in: accounting methods; the registration of digital, financial, and intellectual property services; and valuation and exchange rate timing.

Table 2. Portfolio of announced investments by US technology companies in the UK under TPD

|

Company |

Investment value (billion pounds) |

Project objective |

|

Microsoft |

22 |

AI infrastructure, data centres and construction of the most powerful supercomputer in the UK (in collaboration with Nscale) |

|

|

5 billion |

Construction of a new data centre in Waltham Cross and expansion of research, development and engineering activities over two years |

|

CoreWeave |

1.5 billion |

Investments in AI data centres and their operation (in collaboration with DataVita in Scotland) |

|

Salesforce |

1.4 billion |

Establishment of an AI hub in the UK and development of R&D activities |

|

AI Pathfinder |

> £1 billion |

Commitment to launch an AI computing centre in Northamptonshire |

|

BlackRock |

0.5 billion |

Investments in data centres for businesses |

|

Scale AI |

£40 million |

Expansion of European headquarters in London and increase in employment at British companies |