Vaccine Diplomacy: A Tool in the Rivalry for Influence in Latin America

The uneven access to COVID-19 vaccines in Latin American countries has resulted in a widely varied pace of immunisation. The region has relied mainly on direct purchases from China and Russia, among others, the global COVAX initiative, and donations from the U.S. and other countries. Russia, China, and the U.S. in particular are using this “vaccine diplomacy” to boost their own political and economic influence in Latin America. The EU has been trying to position itself against that rivalry, for example, through significant funding for vaccine access and distribution initiatives. These efforts require, however, more efficient promotion of the Union’s engagement.

_sm.jpg) Fot. Esteban Biba/EFE

Fot. Esteban Biba/EFE

Latin America’s 20 countries comprise nearly 650 million inhabitants, or more than 8% of the world's population. To date, the region has registered almost 44 million infections and 1.46 million deaths linked to COVID-19—almost 20% and 32% of cases worldwide, respectively. The enduring restrictions in most of the region have not helped to prevent further waves of infection. These attempts have been challenged by societal specificities, for example, a large informal labour market, inefficient healthcare, and new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Vaccination campaigns are key to tackling the pandemic in the region, but certain difficulties hinder them.

COVID-19 Vaccinations

More than 54% of the residents of Latin America have had at least one jab, and 35% have received all of the required doses. The countries’ individual progress ranges widely, though (see Table 1). With 73% of their populations fully vaccinated, Uruguay and Chile are at the top of the statistics. Brazil and Mexico—the most populous in the region—are just 38% and 32%, respectively, but have inoculated the highest number of people. The poorest countries have the worst record, especially Haiti (0.2%), Nicaragua (4.2%), and Guatemala (11.4%). Venezuela, which has been in crisis for years and is internationally isolated, is at 14.9%.

In obtaining vaccines, most countries in the region have relied on individual purchases (see Table 2) and supplies from COVAX, the global mechanism for broader access to COVID-19 vaccines (Bolivia, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador are eligible for free doses). In recent months, foreign donations have become an important source (see Table 3). Several countries have signed manufacturing agreements. Vaxzevria, the official name of AstraZeneca vaccine, and CoronaVac, by Sinovac, a Chinese company, are both produced in Brazil. Pfizer’s vaccine (Comirnaty) will be made there from 2022. There are attempts to produce a Brazilian vaccine as well. Chile produces CoronaVac, and Argentina and Mexico manufacture Vaxzevria and the Russian Sputnik V (which Peru also plans to make starting next year).

Cuba is a distinct case. It does not participate in COVAX and has developed its own vaccines. In July, the national regulator, CECMED, certified the use of the Abdala vaccine, and in August, two others, Soberana 2 and Soberana Plus. It stated that their effectiveness exceeds 91%, but the data have not been reviewed independently. Nevertheless, mass vaccination began in Cuba in May despite the lack of CECMED approval. Venezuela and Iran have participated in the tests and are using the Cuban immunisation agents. A sharp increase in infections in August, however, forced Cuba to use Sinopharm doses donated by China.

Lengthy negotiations with vaccine manufacturers were one of the factors behind the low pace of obtaining doses. For example, the Argentine and Peruvian governments criticized Pfizer’s demands for extensive liability protection. The lack of cold storage infrastructure was also a barrier for some countries. Delays in deliveries were a common difficulty; for example, Bolivia cancelled its contract with the Indian Serum Institute. COVAX deliveries also have been sluggish. While it aims to provide doses for 20% of the eligible countries’ population by the end of 2021, or about 127 million people in Latin America, proportionally, the region has received only about 45 million doses since March.

Involvement of Major Suppliers

Comirnaty and Vaxzevria comprise the highest portions of the doses supplied or ordered. CoronaVac and Sputnik V are next, and China and Russia have been most active in vaccine diplomacy in Latin America where they use their respective vaccines to improve their international image and increase their political influence. The speed of the vaccines’ development, competitive contract terms, and intensive promotion of the vaccines and aid activities support these countries’ efforts.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, China has supported Latin America with sanitary supplies and equipment. In July 2020, it offered Latin American and Caribbean countries a $1 billion credit line for the purchase of Chinese vaccines. Some of the jabs were donated to selected governments. In June, for example, Sinovac gave 50,000 doses for the Copa America football tournament. At the same time, China has been pursuing its political goals. It tried to pressure Honduras and Paraguay to rescind their diplomatic recognition of Taiwan in exchange for Chinese vaccines. The Paraguayan government reacted by calling on the Taiwanese authorities for support, and they in turn helped Paraguay with vaccine purchase contracts. Brazil and the Dominican Republic reportedly secured a large supply of Chinese jabs after unblocking the participation of Huawei in 5G infrastructure development. Colombia recognised human rights progress in China at the UN Human Rights Council shortly after receiving 500,000 vaccines from Sinovac. However, data about the low effectiveness of some of the Chinese vaccines has turned out to be troublesome for China. Chile and Uruguay, whose rapid vaccination rates are due to the use of Chinese vaccines, decided to administer a third dose by other manufacturers.

For Russia, preliminary data on the high effectiveness of its Sputnik V vaccine spurred interest, but, from the beginning, there have been issues with timely deliveries, also in supplying components for its production. For example, the delay in receiving a key ingredient to produce the second dose forced Argentina to use other vaccines. There also have been reservations about the transparency of the manufacturing process, with the Brazilian regulator withholding authorisation of Sputnik V for this reason. Sale of the vaccine to Bolivia gave Russia the opportunity to unfreeze some projects, including the construction of a nuclear power plant which involves Rosatom, and to initiate cooperation in the exploitation of Bolivian lithium deposits.

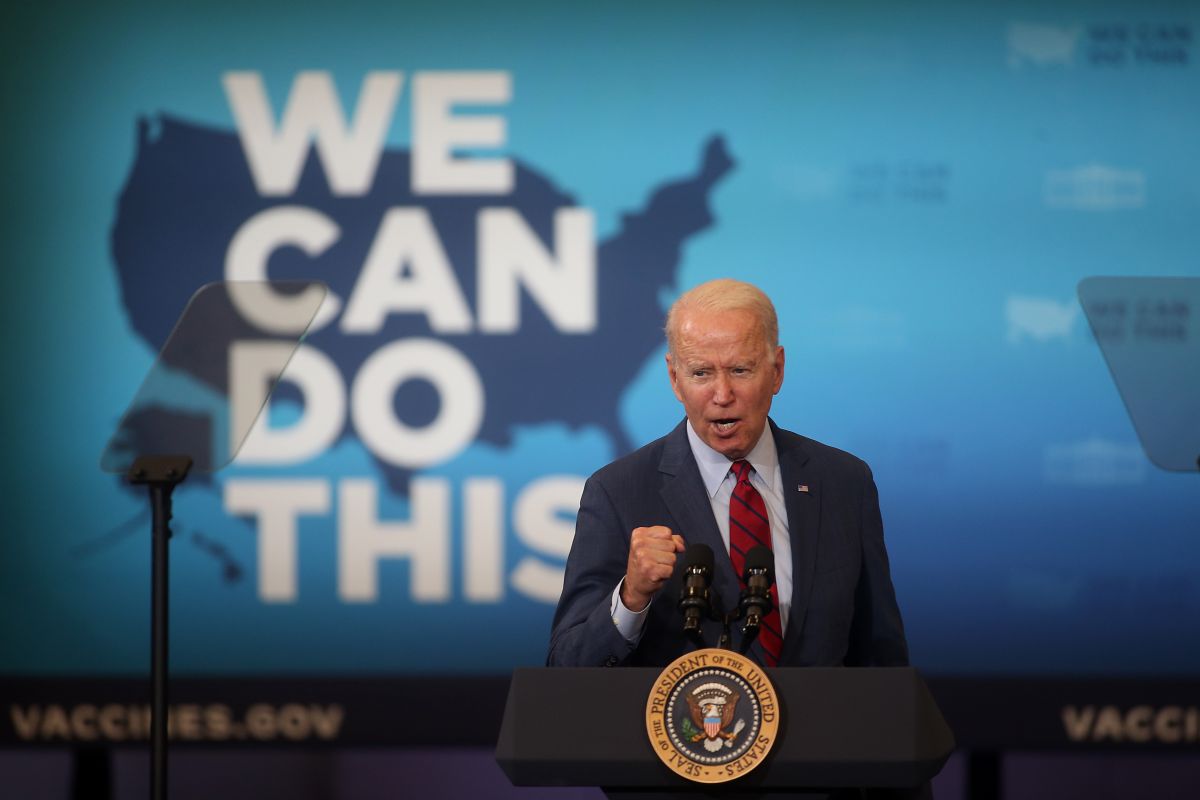

Since the start of the pandemic, the U.S. has provided support to the region as part of development aid, but was very late in joining the foreign donations of vaccines. The Biden administration pledged $4 billion for COVAX and some aid to Mexico, but in March only. In the following months, the U.S. announced the transfer of 80 million doses to various partners: 60 million via COVAX—one third for Latin America and the Caribbean—and the remaining 20 million directly, including countries in that region. In June, it pledged 500 million doses through COVAX for the 92 poorest countries by June 2022. Currently, the U.S. accounts for the largest share of vaccine donations to Latin America.

The EU has offered help to Latin America since the beginning of the pandemic, but the scale of this support has been rather less visible than the other actors. The Union declared one of the largest contributions to COVAX, and Spain stands out when it comes to EU members’ individual aid to Latin America. In September, the European Commission pledged an additional 500 million doses to the neediest countries and announced a joint initiative with the U.S. to boost the global immunisation campaign by improving the production and supply of vaccines.

Conclusions

Vaccine diplomacy has become an important tool for states to build a positive image and strengthen their position in Latin America, particularly for China and Russia. It has enabled them to strengthen political contacts with selected Latin American countries, which will allow them to foster deeper economic cooperation and may help in gaining allies in the region for their international initiatives and in increasing the acceptance of their model of authoritarian rule.

Although the U.S. entered the competition after a delay, its advantage is that it has offered the most aid. However, its commitment will serve more to rebuild its reputation, underlined by the focus on the fight at home with the pandemic, rather than to deter China’s expansion in Latin America.

Vaccine diplomacy clearly benefits individual countries, which is a challenge for the EU and its aspirations of reinvigorating relations with Latin America. The September pledges on vaccine donations and cooperation with the U.S. reinforce the importance of the EU in the global fight against the pandemic. Its support for access to vaccines for such regions as Latin America is in the interest of the Member States as it may help to reduce the risk of the spread of new, potentially more vaccine-resistant variants of SARS-CoV-2. Along with offering this support, the EU should also strengthen its public diplomacy to effectively promote its international aid engagement and reap the benefits of it.

(See tables in Annex below)

%2027%20September%202021_1.png)

%2027%20September%202021_2.png)

%2027%20September%202021_3.png)