The Biden Administration's Vaccine Diplomacy

The United States has begun redistributing procured SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to countries affected by a shortage of doses. The U.S. joined the international COVAX initiative and declared it would provide 500 million doses to it by the end of 2022. The goal of U.S. diplomacy is to improve the country’s image on the international stage and compete with China, which uses vaccines to strengthen its relations with African and Latin American countries.

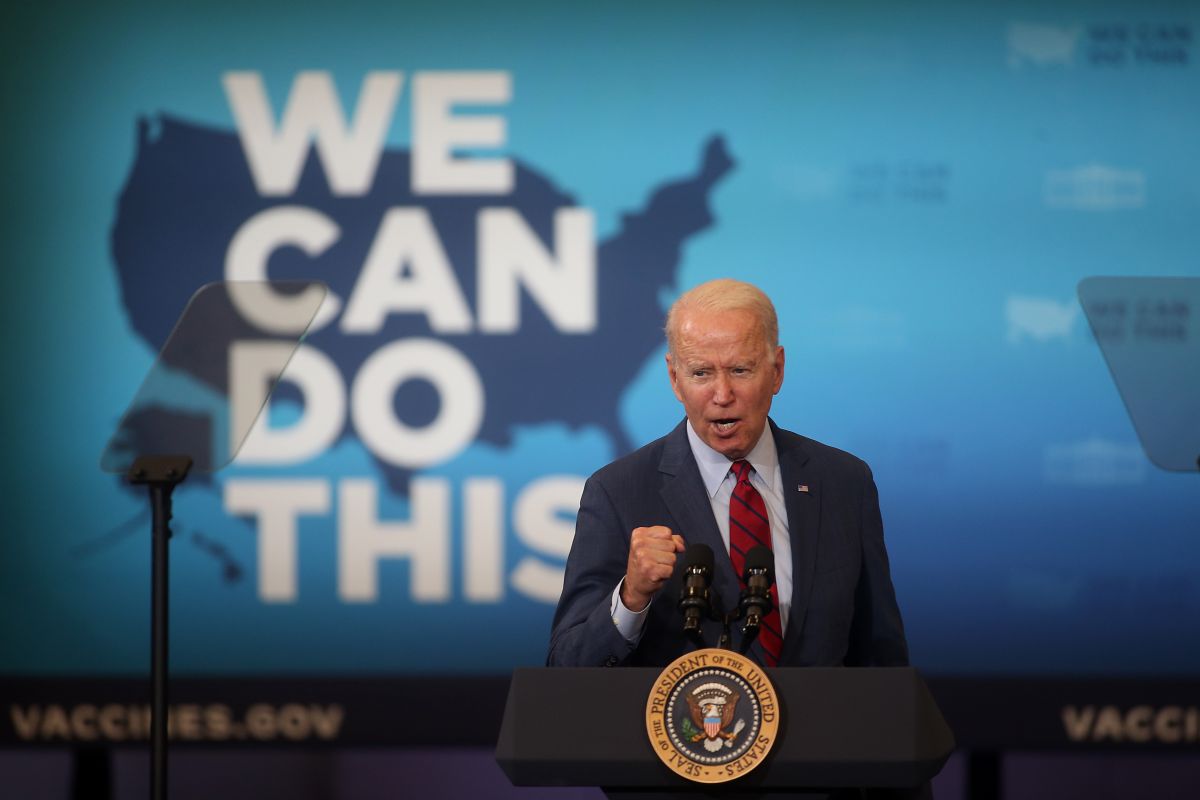

Fot. Bob Karp/Zuma Press

Fot. Bob Karp/Zuma Press

The first vaccines in the U.S. arrived in hospitals as early as December 2020. Research and production was accelerated thanks to the “Warp Speed” public-private partnership programme in which the Trump administration temporarily lifted a number of vaccine regulations and co-financed the research. The administration and Congressionally approved funds ($10 billion) were accepted by various drug-makers, including AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, Johnson & Johnson, and Novavax. Even before taking office, Joe Biden promised that his administration would carry out 100 million vaccinations in his first 100 days in office. The target was exceeded, with about 240 million doses distributed to Americans in that time. As of now, about 50% of U.S. residents are fully inoculated.

Biden administration officials revealed that the outgoing Trump administration left behind no concept for how to vaccinate Americans. The latter also did not formulate a plan for the possible sharing of surplus vaccines with other countries and Trump declared that the U.S. would not join the COVAX initiative due to the participation of the World Health Organisation (WHO) in its creation. In addition, Trump administration agreements with drug manufacturers made it difficult for the U.S. to export doses to countries in need. Support for the global fight against the pandemic was provided by Congress in December 2020—just before the end of its term—when it allocated $290 million for the international organisation GAVI, working on vaccinations in developing countries.

U.S. Initiative

The decision to remain in the WHO was one of the first made by President Biden after he took office in January 2021, and he already had declared the aim to share surplus vaccines. The priority for the new administration, however, was the effective vaccination of U.S. residents, and therefore specific declarations regarding the number of doses that would be sent abroad were postponed until June.

Even before the G7 summit (11–13 June 2021), the White House unveiled a preliminary strategy for the global distribution of the first 80 million doses of the vaccine. According to the plan, 75% is to be distributed via COVAX. The U.S. indicated that the donated vaccine is to be first delivered to Latin America, East and Southeast Asia, and Africa, where they would be distributed in coordination with the African Union. The remaining 25% is to go directly to countries that the U.S. itself deems in need of support. To date, the U.S. has managed to deliver more than 52 million doses of vaccines through the two mechanisms. In addition, the U.S. supported COVAX with $2 billion and declared another matching tranche by the end of 2022.

The U.S. international vaccine effort is a response to similar activity by China, which by the end of June this year had donated or sold abroad about 350 million doses of its domestically produced vaccines. In 2020, the government in Beijing declared its readiness to make vaccines produced by Chinese companies available as a “global public good” and expressed its readiness to distribute doses to nearly 80 countries, including to over 50 free of charge. Despite the unclear results of clinical trials of Chinese vaccines, they are available in many countries. In some, such as Brazil, Chile, and Turkey, until recently they accounted for around 80–90% of the vaccines available.

The EU is also a significant shareholder in the vaccine-sharing programme, supporting COVAX with €2.5 billion (of which €1.5 billion is from the Member States) and pledged to donate 100 million doses to low- and middle-income countries by the end of 2021.

Disputes with Partners

An important element of the Biden administration’s national vaccine policy was the use of the president’s powers under the “Defense Production Act”. Executive orders issued on the basis this law obligated the producers of vaccines operating in the U.S. to fill orders by the American government first. The administration did not formally ban the export of vaccines, but this led to a situation in which the companies were unable to ship their products overseas. Plants located in the U.S. are responsible for about 30% of global vaccine production. Therefore, the decisions by first Trump and then Biden sparked accusations by other governments struggling with a lack of vaccines (e.g., South Africa, India), which in October 2020 criticised the U.S. and other rich countries at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), accusing them of a lack of solidarity. A coalition of states was formed that submitted to the WTO a motion to temporarily suspend the intellectual property rights to COVID-19 vaccines, thus seeking to launch its own production. The motion was later supported by some progressive members of the Democratic Party who in April 2021 backed the call of former heads of state and NGOs to drop patent protection.

In May, the Biden administration announced its support for the relaxation of WTO patent rules. This was met with an immediate reaction from both pharmaceutical industry associations and the governments of the countries in which those companies are registered. Vaccine manufacturers said the move would be counter-productive and create chaos in the market, thereby harming global production efforts. The leaders of the European countries where vaccine companies are operating or registered have joined the critics of the U.S. decision. German Chancellor Angela Merkel expressed her concern about the effects of a possible suspension of intellectual property rights on the quality of vaccines produced. The European Commission also expressed a similar opinion. Ultimately, the states opposed to the changes led by Germany managed to delay proceedings on this issue.

Conclusions

The fight against the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects is becoming another area of the U.S.-China rivalry. In the early days of vaccine production, U.S. policy was focused on meeting its own needs. From the very beginning, China tried to use the vaccines produced by its pharmaceutical industry as a foreign policy tool. This dented the image of the U.S. abroad, already weakened by the Trump presidency in general, as a superpower committed to solving global problems. It will be difficult for Biden to strengthen the U.S. position in this dimension, as even though the redistribution of vaccines from the U.S. is gaining momentum, it still lags China’s reach. This is especially the case for a large number of smaller countries affected by the pandemic that still have no alternative to Chinese-made vaccines.

The WTO-level dispute on vaccine intellectual property rights has also highlighted the difference of views between the European Commission and some EU countries, and the U.S., as well as shown the lack of determination by the American administration to reach out to the pharmaceutical industry. President Biden, who bases his foreign policy on values, has not taken decisive action to create the capacity to produce vaccines in the countries that need them most, thereby further undermining the U.S. position vis-à-vis China, which has supported a similar initiative by India.

It is in Poland’s interest to deepen cooperation and coordination in the EU with regard to securing manufacturing infrastructure and legal solutions that will be useful in the event of another outbreak. The Polish government should consider taking a position on the EU and WTO forums regarding the facilitation of the use of intellectual property rights involving preparations of strategic importance. Poland may also act for the benefit of the Eastern Partnership countries, which are struggling with the lack of doses, by persuading the EU to increase the number of vaccines transferred to those countries. Moreover, from the perspective of both Polish-American relations and the building of domestic production capacities, supporting efforts to loosen intellectual property rights to the production of pharmaceuticals will be in Poland’s foreign policy interests.

|

U.S. Vaccine Donation to: |

Doses (each) |

|

Philippines |

3.2 million |

|

Haiti, Costa Rica, Moldova, Bhutan, Uruguay, Jordan, Ethiopia, Panama |

0.5 million |

|

Nepal, Honduras |

1.5 million |

|

Indonesia, Brazil, El Salvador |

3 million |

|

Bolivia, Malaysia, Canada, South Korea, Laos |

1 million |

|

Vietnam, Ecuador, Peru, Ukraine |

2 million |

|

Afghanistan |

3.3 million |

|

Guatemala |

4.5 million |

|

Bangladesh |

5.5 million |

|

Colombia, Pakistan |

2.5 million |

|

Mexico |

1.3 million |

|

Argentina |

3.5 million |

|

Gambia, Senegal, Djibouti, Burkina Faso, Zambia |

0.15 million |