Omicron: No Global Solidarity on the Pandemic

Immediately after the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced a new coronavirus “variant of concern” called omicron on 26 November, more than 50 countries blocked travel to and from South Africa and neighbouring countries. WHO, African states, and the UN Secretary-General have accused the rich northern states of the selective use of inadequate measures that harm southern countries. To end the pandemic, it will be necessary to reduce the growing discrepancy between the northern and southern states through a solidarity-based approach to the fight against COVID-19.

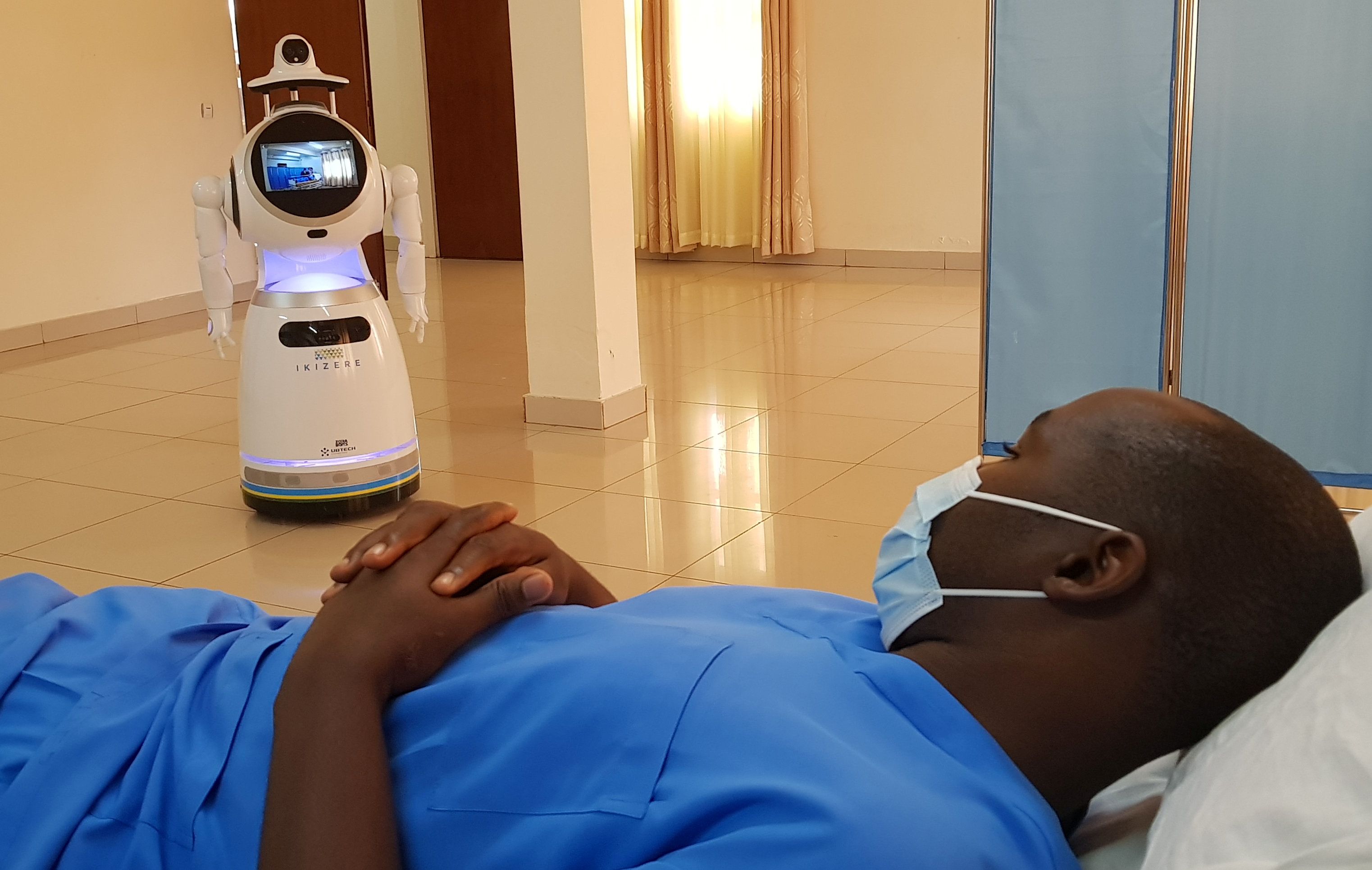

Fot. AFOLABI SOTUNDE/Reuters/FORUM

Fot. AFOLABI SOTUNDE/Reuters/FORUM

The Beginning of the Fourth Wave in Africa

Since mid-November, when the pandemic in Africa seemed to be dying out, the number of infections in the continent’s most-affected country, South Africa, has started to increase again. Within a month, infections rose from 400 cases a day to more than 20,000, and the occupancy of hospital beds increased tenfold. The fourth wave of the pandemic in Africa has been driven by the new omicron strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It has quickly become dominant in the southern part of the continent. The first studies indicate higher contagiousness, with three times more re-infections among people who previously had COVID-19. However, there have been fewer recorded severe disease cases and fewer deaths in proportion to the infections. Nevertheless, concerns are rising about the resistance of the new variant to available vaccines, especially in countries where most of the population has already been vaccinated.

The new variant was identified in parallel by leading laboratories in Botswana, South Africa, and Hong Kong in the second half of November. It was genetically more different from the previously observed strains. Hence, African scientists in the course of their work kept the global scientific community informed about the details of the obtained genetic sequences through the GISAID system, which is used by genetic laboratories during the pandemic. The new variant from South Africa was submitted to WHO on 24 November at a very early stage of the research. This was intended to help the quick development of a common global response.

Africa Stigmatised by Omicron Discovery?

Immediately after the identification of the new variant, rich northern states, restricted travel from areas deemed at risk of contact with omicron. Along with South Africa and Botswana, they included Lesotho, Eswatini, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Malawi and Angola. The policy, though, was inconsistent, as the restrictions did not apply to, for example, the Netherlands where the new variant had been detected in samples taken earlier than those from South Africa, or to other European countries, such as Norway or the United Kingdom, where outbreaks of the virus had already been observed. The addition of Nigeria to the British “red list” on 6 December although it had fewer cases than some European countries, strengthened the sense of stigmatisation of the continent Ultimately, this list was abolished on 14 December.

The suspension of connections with parts of Africa also resulted in supply problems for African laboratories in accessing reagents, which made further studies of the first cases more difficult. The restrictions also increased the economic pressure on the countries most severely affected by the socio-economic effects of previous lockdowns and without reserves to mitigate their effects, for example, by supporting businesses. In this context, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus criticised the Western world’s approach as selective, with South African and Nigerian leaders and UN Secretary-General António Guterres describing it as “travel apartheid”. This term is, of course, provocative and controversial as it ascribed the richer northern states of morally reprehensible intentions. However, it also reflected the logic behind their separating themselves from Africa. The northern states’ approach was certainly influenced by fear of the low level of vaccination in most of Africa, which is a situation that favours the emergence of new virus mutations.

Difficulties with Vaccinations

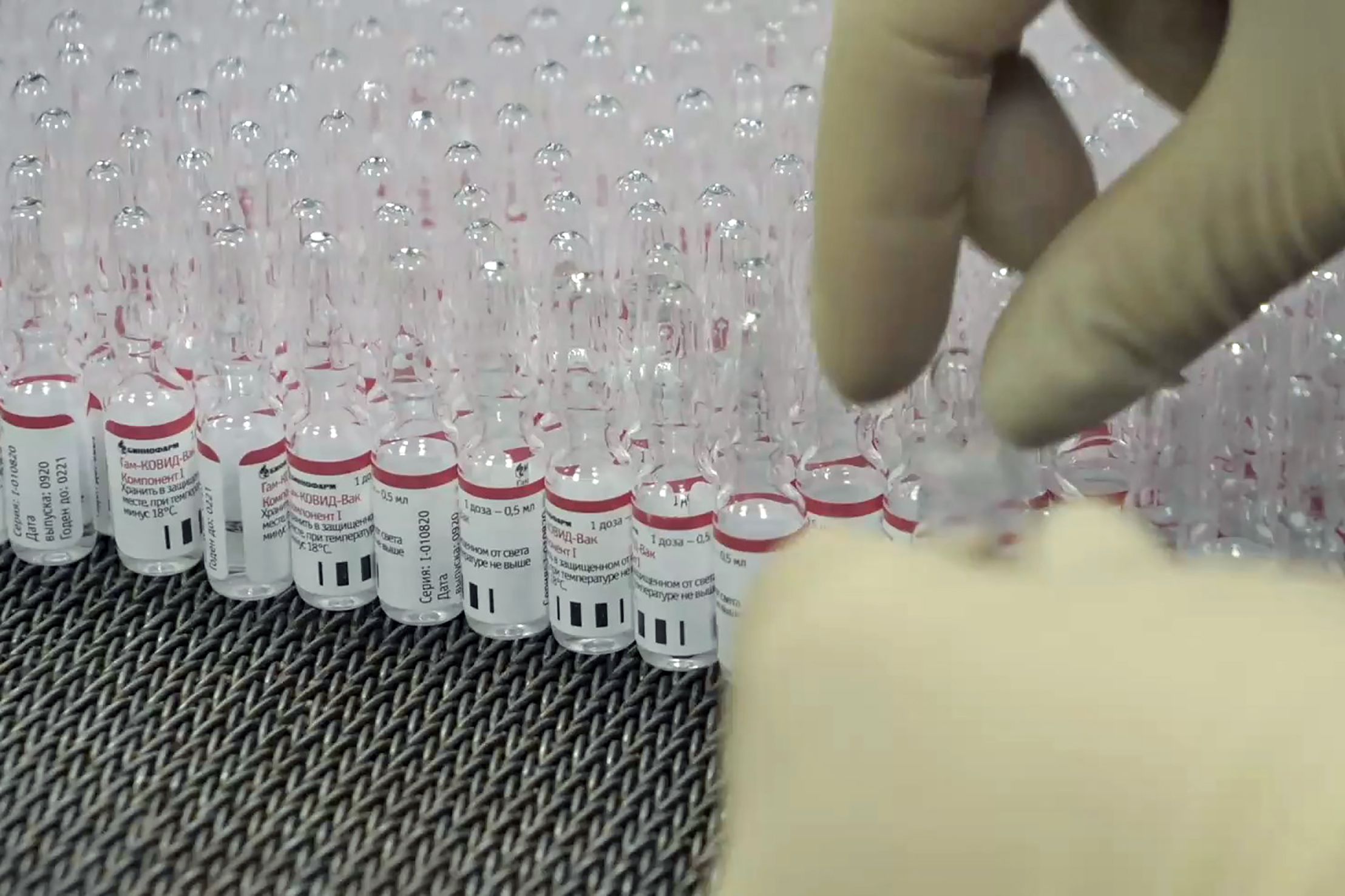

At the time of the appearance of omicron in South Africa, about 24% of the population was fully vaccinated, compared to an average of just 7% for the continent as a whole (in many countries, this percentage is closer to 1%). Throughout 2021, access to vaccination was the lowest in Africa, mainly due to the departure in policies of the richest countries and most influential international institutions from the principle of a global, even distribution of protective measures declared at the beginning of the pandemic, to policies reflecting “vaccine nationalism”. The resurgence of the virus has led these states to accumulate large reserves that often exceed their own needs, often at the expense of their international commitments. This hoarding has hampered the implementation of the COVAX programme, on which the African Union (AU) states initially relied as they did not have their own vaccine production capacity. COVAX initially planned that 20% of the 1.3 billion people in Africa would be vaccinated by the end of 2021. This was not an overly ambitious target in terms of the global demand. However, its implementation turned out to be impossible when the largest vaccine supplier for the programme, the Serum Institute of India, stopped deliveries. The delays accelerated with a global breakdown in confidence last spring in the AstraZeneca (AZ) vaccine, initially dominant in COVAX. For example, after the emergence of the delta variant, South Africa decided not to accept the AZ vaccine, which it believed—wrongly, as it turned out later—did not provide sufficient protection. With COVAX in crisis, the African Trust for Vaccine Acquisition (AVAT), began to play a leading role in ensuring the availability of vaccinations for the countries of the continent. This AU-dependent agency, in partnership with UNICEF, set the goal of providing vaccinations to 60% of the continent’s population by the end of 2022. The vaccines were to be obtained commercially or through aid programmes from all suppliers. Ultimately, the flow of vaccination doses into Africa visibly accelerated only around the beginning of December. By mid-month, a total of about 430 million doses had been distributed.

Difficulties with obtaining COVID-19 vaccines were an impulse to increase the continent’s own production capacity of protective agents. Before the current pandemic, 0.1% of the demand for vaccines against infectious diseases in Africa was covered by domestic supply. Currently, there are several plants on the continent that fill vials with COVID-19 vaccines from external producers, mainly Chinese Sinopharm. The actual production of the vaccine on the continent is expected to start next year in Senegal.

WHO, by supporting the expansion of the production base on the continent, is lobbying for the loosening of the intellectual property rights of the largest producers. A similar step allowed for a breakthrough in the fight against HIV/AIDS, especially in Africa, in the 1990s. To achieve a similar result, in October WHO commissioned Afrigen Biologics & Vaccines, a South African startup, to copy the Moderna mRNA vaccine. This would allow the production of an identical preparation for the needs of developing countries without waiting for the results of negotiations on the suspension of patents within the WTO. While previously the EU was against the overwriting of patents, the advent of omicron made it possible to revise this approach. The EU negotiating team may propose an exception for COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers.

Conclusions

The reaction of much of the Western world after identifying the omicron variant to blocking connections with African countries is symptomatic of the crisis in global solidarity in dealing with the pandemic. It has strengthened the conviction in African countries, and the more broadly global South, that the richer parts of the world are not interested in a joint effort to fight the pandemic. This may harden the positions of, for example, AU countries ahead of the EU-Africa summit expected in spring 2022, including in commercial matters. It may also result in a situation in which the discoveries of new mutations of the virus will not be shared as quickly or as transparently as in November, fearing the possibility of similar, sudden restrictions threatening the countries of origin.

The occurrence of the omicron variant has shown that the pandemic will not be stopped without inoculating the entire globe. It reaffirms the limitations of “vaccine nationalism” and highlights the need to improve global anti-pandemic mechanisms. This reality may contribute to the loosening of intellectual property rights with respect to COVID-19 vaccines. The EU stance on this matter should favour this move, and it should support work on an anti-pandemic treaty. In view of the growing importance of the Chinese and U.S. vaccine diplomacy in Africa, it should also support the AU’s plans to achieve a production capacity of 60% of the vaccines needed in the coming years.