The International Race for a COVID-19 Vaccine

A Race of Powers

According to WHO, there are more than 191 studies on a COVID-19 vaccine worldwide, 40 of which are in clinical trials. Research entities from China, Russia, the U.S., and the UK are the most advanced in the research—the third stage, which if successfully completed, clears the drug to be introduced to the market.

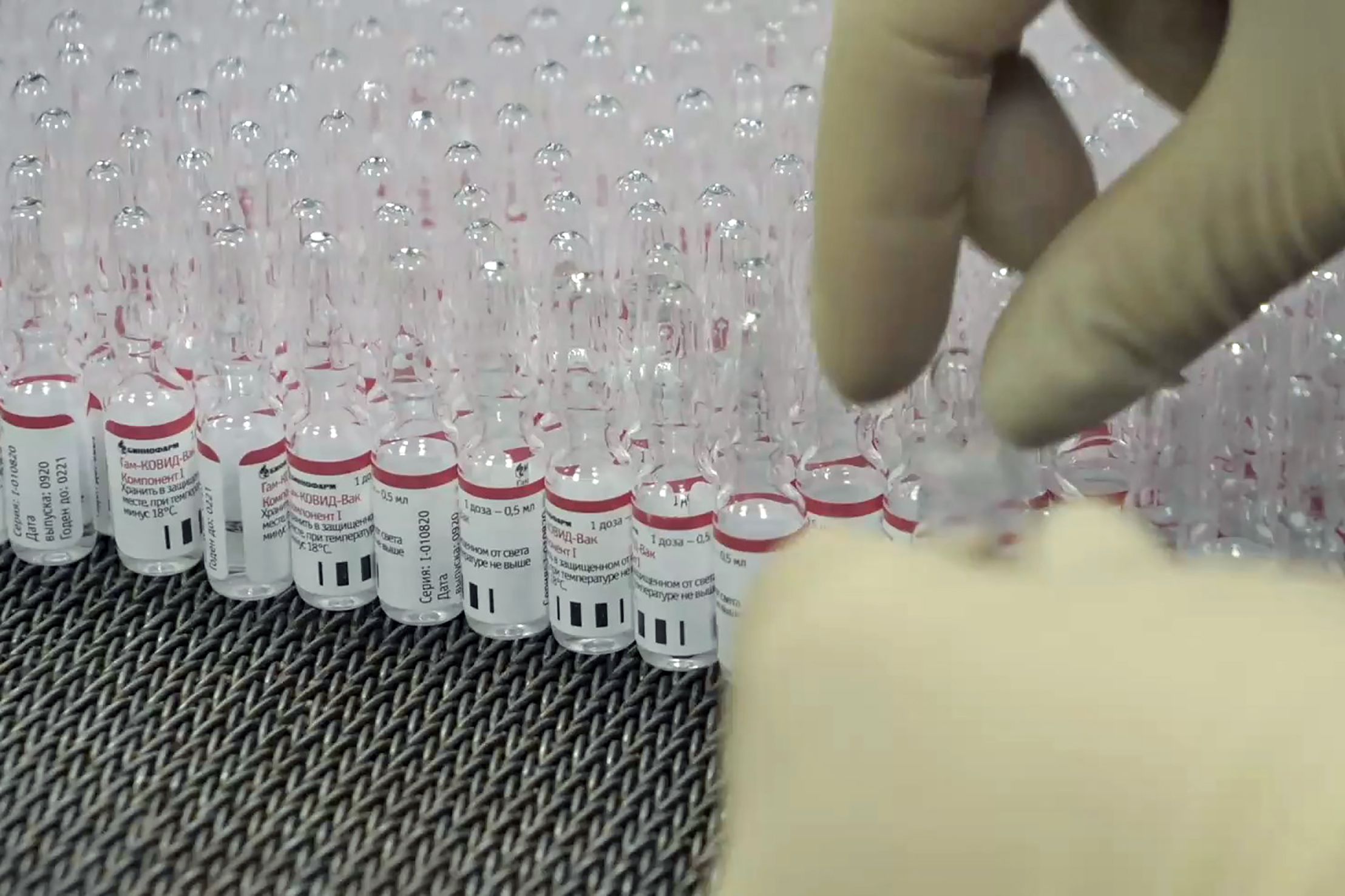

Russia, where the burden of research has been taken on by state institutes, was the first in the world to register a vaccine against COVID-19 (on 11 August). It plans to distribute the vaccine inside the country starting at the turn of October to November and then export it from early 2021.

Almost a third of the companies and institutes around the world whose work is in the clinical trial phase, and as many as four of the nine research consortia that have passed to the third stage of research, come from China. American and British intelligence services have accused Russian and Chinese hackers of stealing data from Western companies, but it is difficult to determine to what extent it actually allowed them to speed up work. Also in the third phase are vaccines by four American corporations (one of them, Pfizer, cooperates with the German BioNTech and the Chinese Fosun Pharma) and the research project of the AstraZeneca consortium and the University of Oxford (UK).

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the U.S. authorities have adopted a strategy aimed at first providing 300 million vaccines by January 2021 for domestic needs (Operation Warp Speed). They allocated more than $12.3 billion to this programme. U.S. vaccine companies will mainly supply the American market but also Canada and Europe. On the latter markets, however, they will face strong competition. AstraZeneca, which declares it will sell its vaccine based on reimbursement of the low costs of production, signed the first contracts with Germany, France, Italy, and the Netherlands in July, and then with the EU, Australia, and Brazil (3 billion doses in total).

China and Russia also took up the fight for the several hundred billion vaccinations global market (depending on the manufacturer and the type of agreement between countries, the price of one dose of a vaccine varies widely, from $3 to $145). The Chinese authorities have announced that they will launch multi-billion dollar “vaccine loans” for countries in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Russia has so far received initial orders from around 20 countries (including Mexico, India, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia) and intends to produce 500 million doses for export in 2021 in cooperation with those countries. Both Russia and China also use vaccines as an instrument of soft power and to build a positive image in foreign policy, for example, China has reserved 100,000 free doses for Bangladesh, and Russia has announced a priority reservation for Belarus.

Major International Initiatives

WHO is also taking steps to develop and distribute a COVID-19 vaccine. Together with the non-governmental organisation CEPI and the Gavi coalition, it implements the COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) Facility, which financially supports 10 research projects, including ones from China, the U.S., and the EU, and an increase in production capacity. Its goal is to produce 2 billion doses of vaccines, including 1 billion for developing countries, by the end of 2021. They are to be made available at affordable prices to WHO members and at a volume sufficient for each country to vaccinate about 20% of their population. It aims to prevent a situation in which developing countries are deprived of access to vaccines because of high prices or reservations on stocks by wealthier nations. Moreover, under the C-TAP initiative, WHO encourages companies to voluntarily license their vaccine patents to the Medicines Patent Pool Foundation, which would sub-license them to generic medicines manufacturers. It also calls for the open-access publication of the results of research and clinical trials and making public funding of research conditional on universal access to the results.

The support for the WHO’s activities is limited. Although 172 countries have joined COVAX, the organisation has so far collected just over $2 billion out of the estimated $16 billion necessary for its implementation. China, Russia, and the U.S. have not joined the initiative. They treat COVAX more like a competitor because access to cheaper vaccines will reduce the political and financial benefits they could otherwise derive. In this context, the EU is gaining importance, having gathered about €2.3 billion from donors to support COVAX, and on 31 August, the Union officially joined the initiative. C‑TAP, on the other hand, has received support from only 39 countries by September, almost exclusively developing ones. Countries where major pharmaceutical companies are headquartered, for example, Switzerland, the U.S., and the UK, oppose it.

Among regional initiatives, the EU’s actions to ensure rapid access to the vaccine for inhabitants of its member states are noteworthy and in line with its COVID-19 vaccine strategy announced at the end of June. By 10 September, the EU initially agreed with the six consortia (four are in the third stage of research) a supply of about 1.3 billion doses with an option to buy an additional 480 million, although most of the contracts are not yet concluded. One of the beneficiaries will be Poland, which has not joined COVAX, believing participation in the EU programme is sufficient.

Challenges

The most important obstacle to the global implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine is production-capacity constraints. The world supply will reach 1 billion units not earlier than in the first quarter of 2021 while the demand is 7.8 billion. At the same time, rich countries have already reserved them for their own citizens—besides the U.S., the UK, and EU countries, also Japan (490 million) and Australia (125 million). This means that in the coming year they will receive the first doses. Thus, the delivery time to developing countries will be longer, preventing them from quickly vaccinating the most vulnerable groups (healthcare workers, the elderly, etc.). The shortage may be eased by vaccine-producing countries that have curbed reservations—China (only 220 million “for security purposes”) and Russia (did not declare that doses would be reserved for its own citizens at all).

Experts and NGOs are calling for COVID-19 vaccines to be a “global public good”, available to all countries at prices close to the cost of production. However, despite formally endorsing this idea, the EU and most of the developed countries where research is conducted have not attempted to implement it. For example, they have failed to ensure that companies whose research is publicly funded share their results, which would facilitate an increase in supply and allow prices to fall.

The consequences of patent protection and vaccine reservation can be partially mitigated by collective initiatives such as COVAX. They can also be limited by so-called “compulsory licensing”—granting manufacturers of cheaper substitutes a production permit without the consent of the patent owners. Trade in such substitutes may, however, be hampered by restrictions resulting from the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) concluded within the WTO in 1994.

It may also be difficult to overcome social fears. Many people declare that they do not intend to vaccinate against COVID‑19—according to research by the World Economic Forum, this includes 40% of Russians, Poles, and French, and over 30% of Germans and Italians. This is linked to concerns about the ineffectiveness and side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine due to the rapid pace of research.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The insufficient willingness of states to cooperate to ensure universal access to a COVID-19 vaccine is one of the greatest challenges to the multilateral resolution of global problem like this. COVAX’s underfunding threatens to delay vaccine distribution under the programme. This will make it difficult to contain this global pandemic and may cause relapses in developed countries as well. This may be partially prevented by the export of cheap vaccines by China and Russia, but it will be associated with both countries obtaining political influence and economic gains.

Poland’s non-accession to COVAX means domestic demand can only be met individually or under agreements concluded by the EU. It is in Poland’s interest to assess the validity of purchasing individual vaccines available thanks to the EU and to monitor advanced projects in terms of possible efforts to extend EU procurement to new items.