Difficult Debate on an Intellectual Property Protection Waiver to Fight COVID-19

The negotiations currently taking place at the WTO on the suspension of, among others, patent protection for vaccines and medicines against COVID-19, are at a standstill. This creates a risk of widening the rift between developing countries, which mostly support the idea, and some developed countries, which oppose it. It also makes it more difficult to increase the supply of patented items, particularly of vaccines, to an extent undermining other efforts by countries and international organisations to contain the pandemic. It is in the interest of Poland and the EU to overcome this impasse.

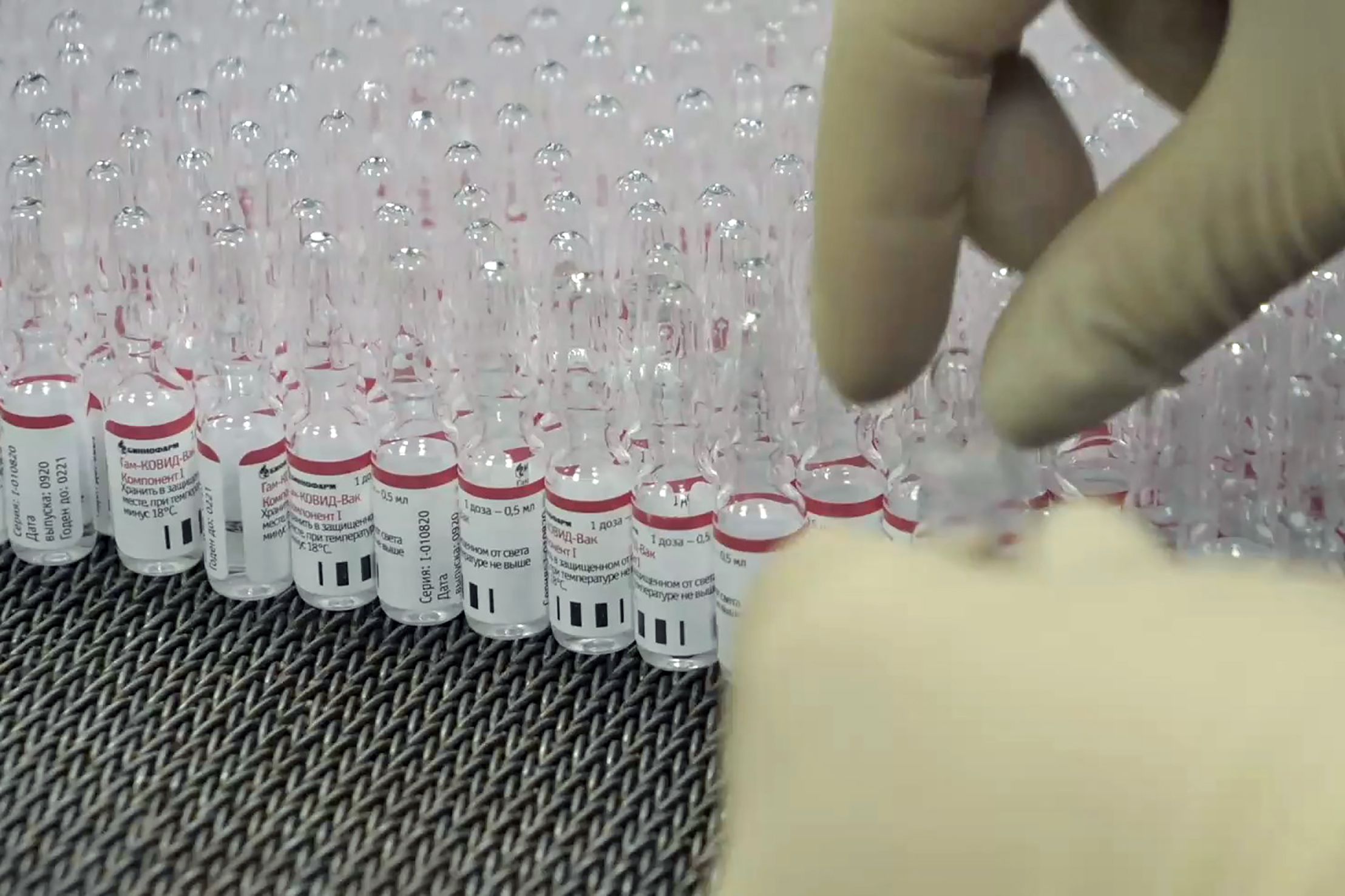

Fot. Reuters/ ANDREW COULDRIDGE/ FORUM

Fot. Reuters/ ANDREW COULDRIDGE/ FORUM

Background of the Discussion

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the widest possible access to diagnostic tests, drugs, or future vaccines against the disease has been a priority for most countries. At the same time, it was widely recognised that developing countries would have the greatest difficulty in achieving this, not least because of their lower research and development capacity. So it was mainly at their request that the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced the C-TAP initiative in May 2020. It was intended to facilitate the voluntary, but paid, licensing by pharmaceutical companies to manufacturers of low-cost substitutes and the transfer of research results and know-how on manufacturing. This would allow production to be undertaken in less technologically advanced countries, increasing supply and lowering prices. However, C-TAP failed because of a lack of willing licensors. The only licence under this formula, one for diagnostic tests, was granted by a Spanish public institution at the end of November 2021.

Developing countries had already found the voluntary approach ineffective by the end of 2020. Consequently, in October 2020, India and South Africa submitted a proposal to the WTO to temporarily suspend the application of part of the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which binds WTO members. Modified in May 2021, the proposal would waive protection of patents, industrial designs, trade secrets (including know-how) and copyrights on vaccines, drugs, tests, respirators, and personal protective equipment used against COVID-19. The waiver would last at least three years, with the possibility of revocation by the WTO once the pandemic is contained. It would allow producers of unlicensed substitutes to avoid being sued in the courts of WTO countries with the threat of an order to halt production and pay damages. It would also make it possible for countries that have not prevented unlawful activity to avoid WTO proceedings that could lead to trade sanctions.

By the end of 2021, more than 120 countries had endorsed the project, including most developing countries as well as China and Russia. On vaccines alone, it was also supported by, among others, Australia, France, Italy, New Zealand, Poland, and the U.S., the directors-general of the WTO and WHO, more than 170 former heads of state, and Nobel laureates. Although the suspension formally requires a three-quarters majority vote, supporters of the proposal are seeking adoption by consensus like other WTO decisions. However, opposition to the waiver is maintained by countries with a strong pharmaceutical sector, including Japan, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK, and by the European Commission (EC). Despite several rounds of talks, no agreement has been reached, even on vaccines. Some countries were hoping for progress during the WTO ministerial conference in Geneva at the turn of November and December. However, it was postponed indefinitely due to the introduction of entry restrictions by Switzerland after the detection of the Omicron variant. This was in line with the existing practice of stalling negotiations.

Arguments of Waiver Supporters

States and NGOs supporting the Indian and South African proposal point out that research on vaccines or medicines (e.g., molnupravir) has been conducted with significant public support, so states should have more say in how its outcomes are used. At the same time, the alternatives to suspension proposed by some developed countries and the EU are ineffective. Donations of vaccines or medicines by wealthy countries are not enough, as the world is facing a global shortage of these products. It is therefore necessary to increase supply by starting production with new players. However, voluntary abandonment of IPR enforcement (as by vaccine manufacturer Moderna in 2020) is occasional. Nor does it provide substitute manufacturers with full protection against lawsuits because of the close links between, among other things, some patents with others owned by other companies and still protected. Pharmaceutical companies are also reluctant to grant voluntary licenses for a fee because, from their perspective, lower supply has a positive impact on price. Even the leader in this respect as regards vaccines, AstraZeneca, has so far licensed its preparation only to two companies, one each in India and South Korea. The compulsory licences provided for in TRIPS that allow countries to grant local manufacturers a licence to produce a given medicine or vaccine in a crisis are also not an optimal solution. The very process of issuing them and the fact that TRIPS limits their scope to patents only (leaving aside, for example, the equally important know-how) makes the start of production difficult and delays it. In addition, corporations often sue states for granting compulsory licenses and happen to win cases, forcing the annulment of licenses. This avenue, therefore, also entails legal uncertainty for states and producers. Moreover, the TRIPS rules make it difficult to export products manufactured under these licences to other countries.

Arguments from Opponents

Countries opposed to the waiver, as well as large pharmaceutical companies and others, believe that the waiver will not be enough to eliminate the problem of limited supply. In their view, this is largely due to, among other things, export restrictions on the raw materials used in production. They also argue that smaller producers, especially from developing countries, lack the adequate infrastructure and highly skilled staff to produce, for example, vaccines of sufficient quality. This argument is contested by manufacturers from Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Morocco, South Africa, and others who signal their ability to undertake production if the waiver proposal is accepted by the WTO. Moreover, manufacturing drugs, which are devoid of a biological component, is much easier, and there are shortages in the world in this regard as well. Opponents of the intellectual property protection waiver also argue that it will not force companies to hand over the know-how necessary for production, which, unlike, for example, patents, is not made public. However, the same problem occurs in the case of compulsory licences, which, among others, the EU has so far considered sufficient to solve the problem of low supply. There is also the argument that the suspension will discourage pharmaceutical companies from innovating in the event of further pandemics, for fear of limited profits despite conducting expensive and risky research. However, particularly in the case of COVID-19 vaccine research, subsidies from states or international organisations have been a major part of the funding.

Conclusions and Outlook

Possible failure of the WTO negotiations raises the risk of a deeper rift between the developed and developing countries and further exacerbates the limited global supply of vaccines and medicines against COVID-19. Chances for a breakthrough are hindered in particular by the low diplomatic activity in this regard by the U.S. and the EC’s inflexible position due to the reluctance of some EU countries, including Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and Portugal, towards the proposal by India and South Africa. The EU is therefore missing an opportunity to play a greater role in the talks, despite its aspirations to be a leader in global health governance. Meanwhile, a compromise could be sought by, for example, setting a stiffer timeframe for the waiver and limiting the measure to vaccines (as proposed by the U.S. and some developed countries), as well as by linking the issue with developing countries’ agreement to other changes in the WTO that the EU seeks (e.g., on fisheries liberalisation).

Enabling broader production of anti-COVID-19 goods by entities from developing countries would be beneficial from the perspective of Poland and the EU as it would make it easier to contain the pandemic on a global scale. It could also be used as a counter-argument to claims in the public debate that vaccination campaigns are in the interests of Western pharmaceutical companies. Poland and the EU could also consider making public subsidies for medical research in the future conditional on limiting intellectual property protection for the resulting solutions, or at least on making the relevant licenses sufficiently widely available.