Azerbaijan Faces Uncertain Fate in the Council of Europe

In January, the Council of Europe (CoE) excluded Azerbaijani delegates from the work of its main plenary body, the Parliamentary Assembly (PA), for one year, citing serious violations of human rights and the organisation’s principles. This was followed by announcements from Azeri authorities that if this decision was not reversed, Azerbaijan could leave the CoE altogether. The organisation should not give way to blackmail from any member, but it would be advisable to try to seek a solution to reduce tensions between it and Azerbaijan. The country’s departure from the CoE would in practice make it impossible for its people and the citizens of other countries harmed by it to seek protection of their rights and compensation before the European Court of Human Rights.

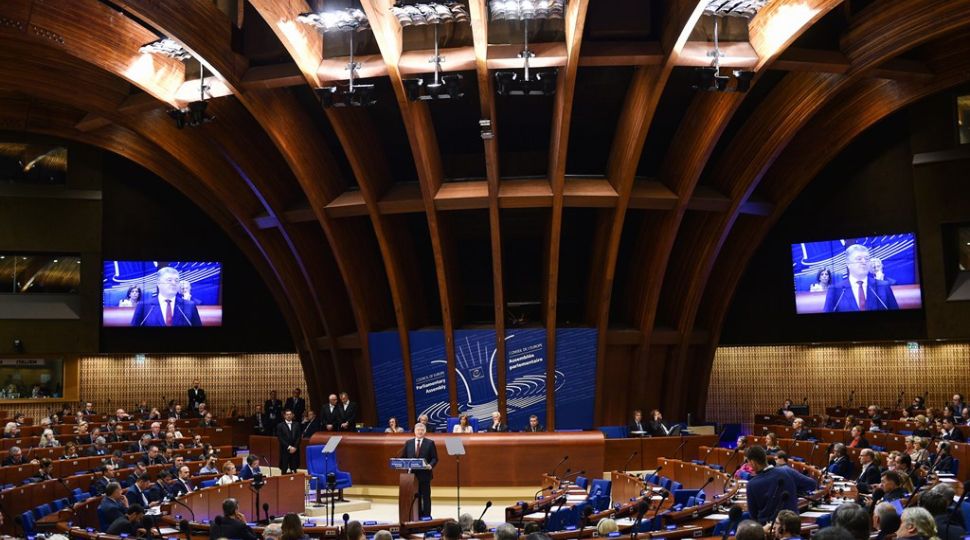

ARND WIEGMANN / Reuters / Forum

ARND WIEGMANN / Reuters / Forum

Azerbaijan and the Council of Europe

Azerbaijan joined the CoE in 2001. Although there were doubts about the state of democracy in the country due to, among others, the OSCE’s recognition of the 2000 parliamentary elections as failing to meet democratic standards, the CoE expected that membership would lead to improvements in these areas and increase the Azeri authorities’ respect for human rights. The initial results were moderately positive, including the release of a number of political prisoners and the ratification of important CoE conventions, such as the 1987 one on the Prevention of Torture and the 1995 one on the Protection of National Minorities.

When joining the CoE, Azerbaijan counted on its support in resolving its dispute with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh (NK) and pledged, among other things, not to use force to do so. In several resolutions issued since 2002, the PA has indeed criticised Armenian occupation of part of its territory and support for separatists in NK, notably in Resolution 1416 of 2005 denying them the right to secede. It also set up an ad hoc committee on NK to support a peaceful resolution of the dispute (although in practice it proved ineffective and was quickly marginalised). The Azeris also were successful in persuading the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) to side with them in judgments that confirmed that the disputed area was not part of Armenia’s territory and that the regime in NK was controlled by Armenia and existed due to its military and financial support.

However, in seeking to increase influence over the CoE, Azerbaijan corrupted some members of the PA, triggering the biggest corruption scandal in its history, dubbed “Caviargate” and publicised by NGOs first in 2012. It resulted in an internal PA investigation in 2017-2018 (contributing, among other things, to the resignation of its president at the time, Pedro Agramunt) and reform of the CoE’s anti-corruption legislation. This also led the organisation to take a closer look at the internal situation in Azerbaijan and to criticise, among other things, the low implementation rate of key judgments of the ECtHR (according to European Implementation Network estimates for 2023, it is around 15%; only Albania has a lower score, at 5%; previously, Russia, removed from the CoE in 2022, had 8%). The CoE’s reservations also included serious violations of democratic standards in successive elections (the last one in February 2024), high rates of political prisoners, and restrictions on freedom of expression and association.

Recent developments

The Azeri offensive into Armenian-controlled areas in 2020 and the second one in September 2023 complicated Azerbaijan’s situation in the CoE. Since 2020. Armenia has brought four cases against it before the ECtHR with requests for urgent orders to, among others, halt the fighting and unblock the “Lachin corridor” connecting the Armenian-controlled part of the NK with Armenia. The Court granted the requests, undermining the legality of Azerbaijan’s actions. The PA also stepped up its criticism. In an October 2023 resolution, it demanded that the security, property, and other rights of the Armenian population fleeing NK be protected and that measures be taken to allow them to return to the area. It threatened that, if these expectations were not met, it would initiate a so-called “complementary joint procedure” for cases of the most serious violations, which involves all the main CoE bodies. Above all, however, it announced the possibility of excluding the Azerbaijani delegation from the work of the Assembly in early 2024.

Aware of the risk of losing the vote on exclusion, the Azerbaijani delegation itself announced in late January 2024 that it was withdrawing from the PA. The Azerbaijani delegates and experts were prompted by disappointment at what they deemed insufficient support from the CoE for their country in resolving the NK situation and a pro-Armenian stance and Islamophobia of the PA. There were also claims that their state belonged to Asian culture rather than European. Of these arguments, the resentment against the ineffectiveness of the CoE’s efforts to settle the NK dispute can be considered relatively accurate—indeed, the organisation has failed in this regard, as has, for example, the OSCE. This was a consequence of the generally low effectiveness of international organisations in resolving such disputes, especially in the post-Soviet area.

Despite the withdrawal of the Azerbaijani delegation, the PA voted a resolution excluding it from its work for 2024 (this is a temporary exclusion, it must be renewed annually). It justified this step on the grounds of, among other things, Azerbaijan’s failure to invite CoE observers to the presidential elections on 7 February this year, problems with the independence of the judiciary and the implementation of ECtHR rulings, and the humanitarian implications of its use of force in NK in September 2023. Its decision was formally valid, although more than two-thirds of the PA members did not participate in the vote (including those from Georgia, Poland, Serbia, and Ukraine). Of those present, only the delegates from Albania and Turkey voted against, while those in favour were mainly from Armenia and Western European countries, including France and Germany. Shortly after the vote, Azeri President Ilham Aliyev signalled that his country would consider leaving the organisation altogether.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Azerbaijan’s respect for human rights and democratic principles is far from CoE standards, and its military actions in NK since 2020 contradict its non-use of force pledges to international organisations, including the CoE. However, the complete exclusion of Azerbaijan’s delegation from the work of the organisation’s main body was a tougher step than when the CoE suspended only some of the rights of Russia’s delegation after the 2014 aggression against Ukraine. Treating it more harshly than an outright aggressor, despite a similarly undemocratic political system (as Freedom House or The Economist rankings indicate) can seem excessive. Ultimately, it was seeking to regain an occupied part of its own territory.

The realisation of Azerbaijan’s threats to leave the CoE would be the first time in the organisation’s history (so far, only one state has been removed from it—Russia in 2022 for its full-scale invasion of Ukraine). This would diminish the human rights protection system in Europe because with Azerbaijan’s exit from the ECtHR, it would make it impossible to seek reparations before the Court by Azerbaijanis and Armenians harmed by hostilities since 2020. It could also entail further erosion of the protection system in the longer term, possibly involving an exit by Turkey, politically sympathetic to Azerbaijan and also criticised for the deterioration of democracy and human rights protection. It would also have adverse effects on the CoE budget, although much less severe than the effects of Russia’s removal in 2022 (Azerbaijan’s contribution is about 0.4% of the budget, while Russia’s was about 7%). Azerbaijan’s possible departure from the CoE would therefore entail an increase in Poland’s contribution to the organisation’s budget, albeit not a significant one with the remaining members picking up more of the bill.

An attempt by the CoE to ease tensions is therefore welcome. A preliminary step could be to halt criticism of Azerbaijan’s actions in NK, from which tens of thousands of people have in fact already fled, rather for good, including probably almost the entire Armenian population that was living there. In return, an absolute ultimatum would have to be given to Azerbaijan to refrain from further claims and military action against Armenia proper, and it should be expected to pay compensation to Armenia and the Karabakh refugees for all human rights violations found by the ECtHR (including property rights). Such an approach could facilitate a gradual normalisation of the situation, while giving Armenia the necessary means to reintegrate the refugees into Armenian society. A further step could be to expect a successive improvement in the enforcement of ECtHR judgments regarding respect for the main categories of human rights in Azerbaijan. However, the current hardline stance of the Azerbaijani authorities suggests that progress in this regard may be difficult. A decision to leave the CoE is more likely after the COP29 climate summit in Baku this November, as doing so earlier could hamper Azerbaijani diplomatic efforts at the event.

Internal developments in Azerbaijan and the increased tensions between it and the CoE suggest that reflection is needed among Western countries as to whether the model based on respect for democracy and human rights remains viable or has lost appeal, and if so, how to restore it.