The Relevance of BRICS after the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

The upcoming 14th BRICS Summit, held during the Chinese presidency of the group, will be an opportunity for China to promote its vision of the international order and for Russia to show that it is not internationally isolated. The BRICS will not, however, become a counterweight to the West, mainly due to the disparity of potentials between China and the rest of the group and especially the tensions between it and India. Among other things, the EU and the U.S. should counteract BRICS members’ disinformation about the war in Ukraine and attempts to blame the global food crisis on the countries imposing sanctions on Russia.

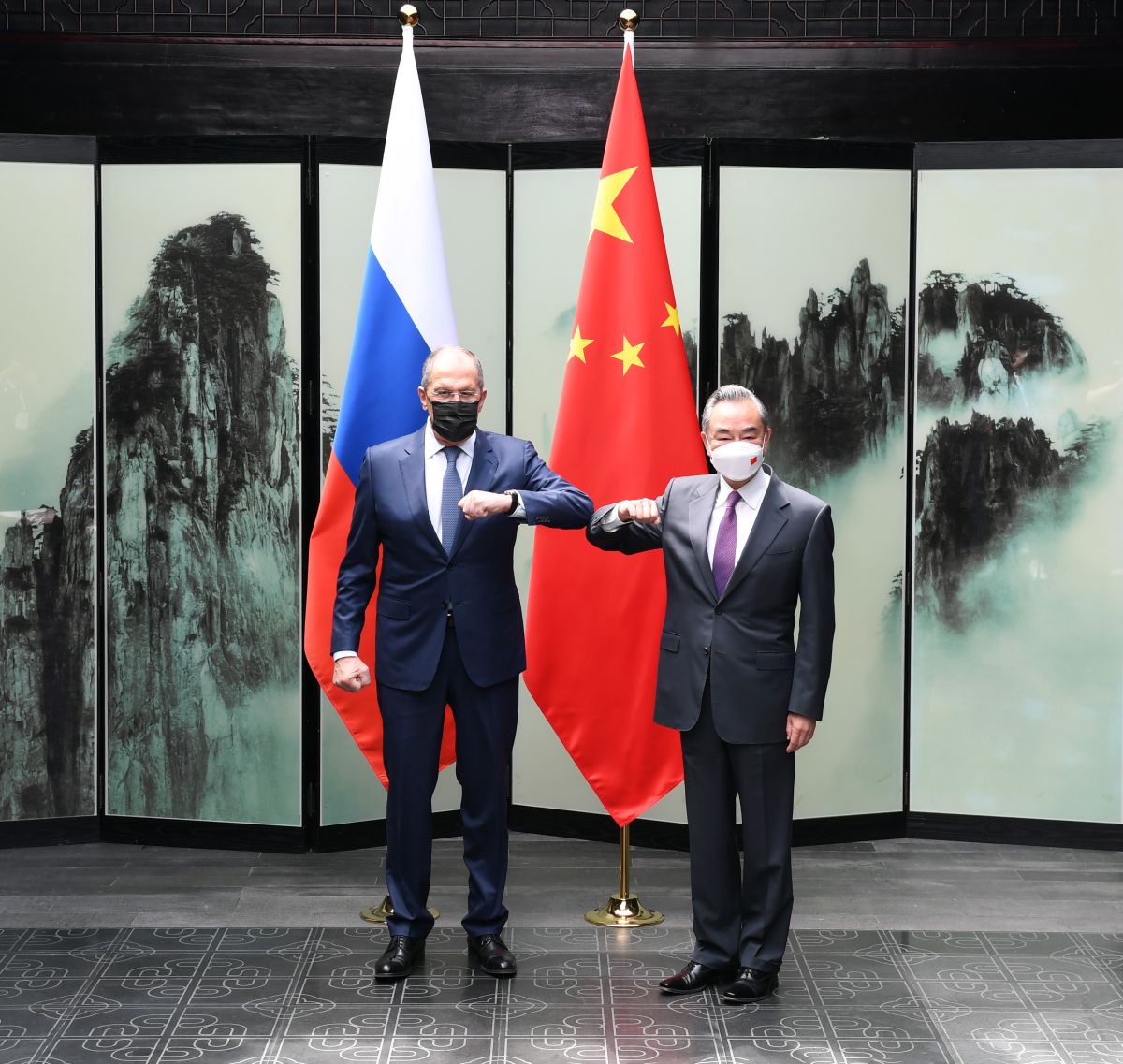

POOL/Reuters/Forum

POOL/Reuters/Forum

BRICS: Status and Challenges.

Existing since 2009, the group is a multilateral cooperation format for the largest non-Western powers from different continents—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Together, these countries account for 40% of the world’s population, 28% of global GDP, and 20% of goods exports. Cooperation between them is composed of three pillars: political and security, economic and financial, and cultural and people-to-people exchanges. In addition to the most visible forum within the BRICS, which is the meetings of leaders, the cooperation is diversified and has deepened in recent years, including the institution of several dozen coordination mechanisms at the ministerial level (e.g., foreign affairs, finance, transport, trade), public institutions (e.g., heads of central banks, statistical offices, security advisers), and non-governmental (e.g., exchanges of scientists or youth). The most tangible effect of the activities so far was the establishment of the New Development Bank in 2014, which by the end of 2020 financially supported 72 investment projects in the member states worth $25.7 billion.

The next BRICS summit is planned for 24 June and is to be held online. The topics of the meeting will include economic recovery after the pandemic, the effects of the war in Ukraine, and the possibility of extending membership (Argentina and Egypt are among the candidates). China wants to revive the cooperation format and use the summit to promote its Global Security Initiative (GSI) and Global Development Initiative (GDI) proposals as alternative models for international cooperation.

Yet, the group’s cohesion suffers from the huge disproportion in the potential of the states to the favour of China, including in the concentration of members’ cooperation with China to a greater extent than with the other partners. However, the main factor weakening BRICS in recent years has been the deteriorating relationship between the largest members—China and India—over border and trade disputes since 2017. The tensions culminated in clashes on the border in Ladakh in June 2020, which nearly led to the cancellation of the BRICS summit that year and prompted India to deepen cooperation with the U.S. and the EU.

Despite some divergence of interests, what unites the members of BRICS is their criticism of the current international system, which they believe is controlled by the West, as well as objections to some Western policies (e.g., interventions in Libya, Syria, supporting democratic movements). The BRICS countries are striving to create a multipolar global order and reform international institutions to gain greater influence in global governance. In recent months, they have criticised the West for, among other issues, blocking a patent waiver at the WTO for COVID-19 vaccines and the slow pace of delivery of the vaccines to developing countries, attempts to combine climate issues with security at the United Nations, and the failure of industrialised countries to meet their obligations to finance the fight against climate change. For all members of BRICS, the format is a useful tool in foreign policy as it strengthens their status and voice in international affairs and allows them to present a rival position to the Euro-Atlantic perspective.

BRICS States’ on the War in Ukraine.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the decisive reaction of the West has given new impetus to renewed cooperation within BRICS. Russia sees it as an opportunity to avoid complete international isolation, while the remaining members want to counter the strong pressure from the West to unequivocally condemn the Russian invasion. For China, BRICS gives it the possibility to improve relations with India by reviving old anti-Western sentiments and appealing to the solidarity of developing countries. That is why Chinese Foreign Minister Wangi Yi arrived in Delhi on 24 March to try to persuade Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to attend the summit during the Chinese presidency. Although India accepted the invitation, the agreed formula of a virtual meeting (officially due to the COVID-19 pandemic) allows Modi to participate without the need for him to travel to China, which he vowed not to do until Chinese troops retreat to positions prior to the June 2020 border clashes in Ladakh.

Most of the BRICS countries have not condemned Russia for its aggression against Ukraine and distance themselves from the policy of Western countries. Only Brazil joined the 141 nations in the UN General Assembly on 2 March supporting a resolution condemning Russia’s actions, while the rest of the group abstained. However, other votes in international forums (including earlier ones in the UN Security Council) and statements by Brazilian politicians indicate that Brazil’s position is closer to that of the other members of BRICS than to the West’s. During the meetings of BRICS sherpas on 13 April and foreign ministers on 19 May, members supported “dialogue and negotiations between Russia and Ukraine” to end the conflict and expressed concern about the humanitarian situation in Ukraine.

In the public discourse in the BRICS countries, the war in Ukraine is often portrayed as having been provoked by NATO expansion, as a proxy conflict between the U.S. and Russia, or as a regional European problem. At the same time, the pressure to condemn Russia and comply with the sanctions is rejected, citing Western hypocrisy, including previous violations of international law (e.g., the intervention in Iraq in 2003) or the purchase of Russian oil by EU countries. The main challenge for BRICS related to the war is rising energy and food prices, which is, however, associated in these states’ perspectives not so much with the Russian aggression, but with the Western sanctions.

Concerns about the impact of unilateral restrictions on the economic and social situation have sparked accusations in India and China that the West is “weaponising” dollar-based trade and the financial system and stirred fears that it could be used against them one day. This has reinforced long-standing discussions about increasing BRICS states’ resilience to Western pressure by reducing the dependency in critical sectors that Russia is trying to take advantage of. For example, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov called on group members at a ministerial meeting on 8 April to switch to national currencies for export-import transactions and to create their own international payment system, financial messaging system, and independent rating agency.

Conclusions and Perspectives.

The war in Ukraine and the criticism of the sanctions imposed on Russia provide the impulse to strengthen cooperation within BRICS and may enable deeper integration of the financial systems of the group’s members. Progress in this area will make it easier for Russia to circumvent the sanctions. Russia will use the summit to show it retains international support for its policy, while the other members will use BRICS to counter Western criticism of their stance on the war in Ukraine. A joint appeal can be expected calling for a “freeze” in the war in Ukraine and pressure on Western countries to limit sanctions, which will be presented as the cause of the global food and energy crises. Due to the lack of consensus on the criteria and procedures of the group’s enlargement, no new members will be admitted soon. India also is not interested in promoting China’s GSI and GDI proposals through BRICS. It is the tensions between China and India that will limit the group’s significance, keeping BRICS from becoming a major coherent bloc counterbalancing the West.

The U.S. and the EU should, however, closely monitor the decisions at the end of the next BRICS summit and counteract its members’ creation of mechanisms to circumvent the sanctions imposed on Russia. In response to disinformation stemming from this group, it is worth intensifying external information campaigns and cooperation with developing countries to emphasise Russia’s responsibility for the global increase in food prices as a result of the blockade by the Russian military of Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea. The dialogues with other BRICS members can also be strengthened so that they do not adopt the Russian perspective in assessing the origins and consequences of the war in Ukraine. In the long term, it is in the West’s interest to respond to the demands of the democratic members of the group aimed at reform of international organisations (e.g., increasing their vote in the IMF or the World Bank, or reforming the UNSC). This will not only improve the credibility and efficiency of these institutions but also will undermine the unity of BRICS by taking away its main rationale for closer cooperation.