Determinants of China's Policy Towards the War in Ukraine

China’s position on the war in Ukraine depends mainly on the stabilisation of China’s internal situation before the 20th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress planned for autumn this year. By holding NATO responsible for the conflict, the CCP reinforces its rhetoric about the legitimacy of the rivalry with the U.S. China’s signals on supporting peace negotiations and not helping Russia to circumvent sanctions are intended to protect China from possible Western secondary sanctions. The prospect of further Sino-Russian cooperation should induce the EU to reduce its economic interdependence with China.

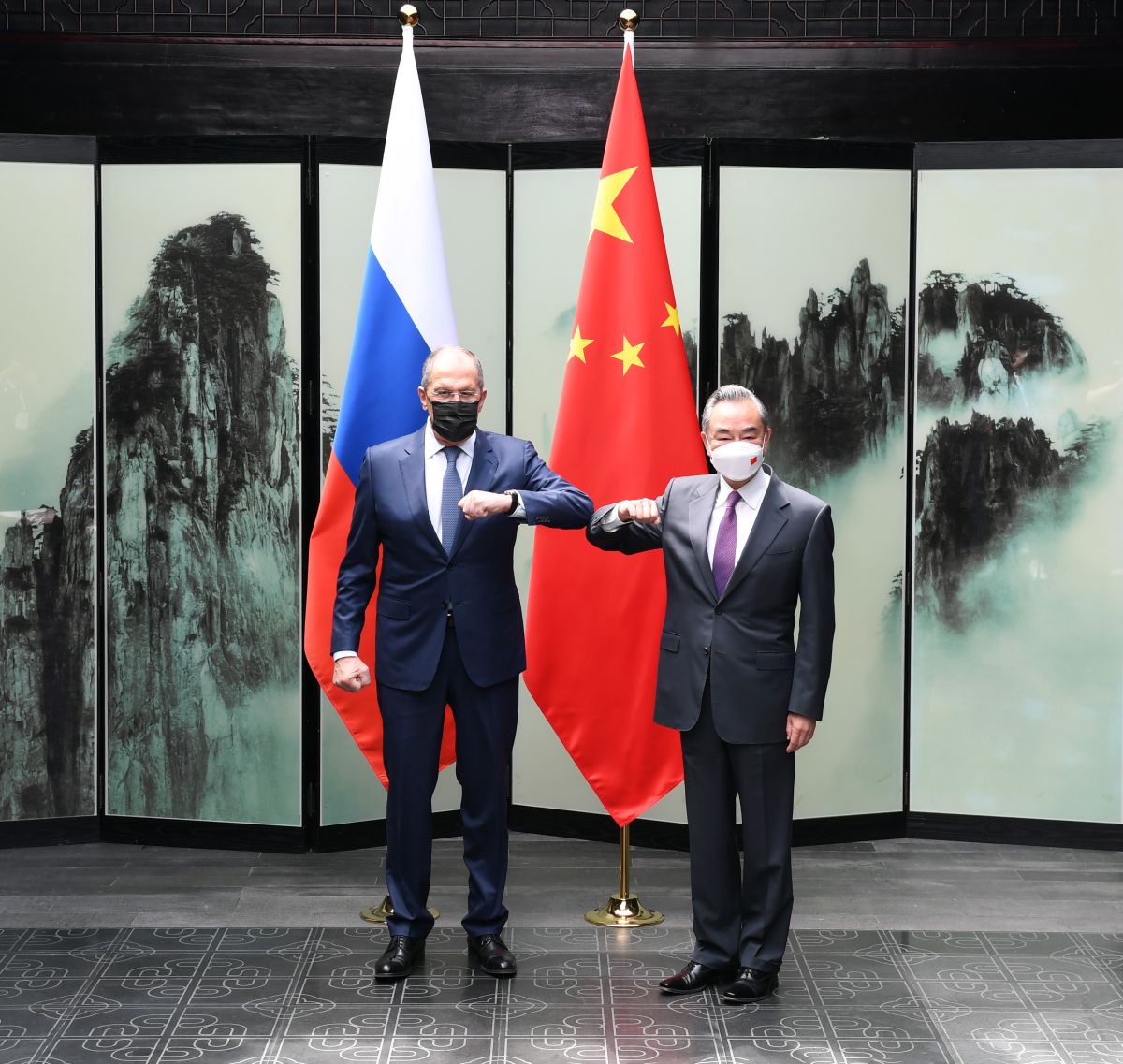

Zhou Mu/ Xinhua News Agency/ FORUM

Zhou Mu/ Xinhua News Agency/ FORUM

Support for Russia

China has supported Russia politically since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Chinese authorities did not recognise the Russian actions as an armed attack, ignoring the responsibility of the Russian Federation for violating international law. China abstained in two UN votes (in February and March) on resolutions condemning Russia. It also voted against Russia’s removal from the UN Human Rights Council.

China denies that sanctions are an effective instrument to end the conflict, and calls for negotiations between the U.S., Russia, and the EU (among others), but without Ukraine. China believes that the talks should include the reconstruction of the European security architecture taking into account Russian demands. At the same time, the spokespersons of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs present content consistent with Russian propaganda, for example, statements expressing doubts about Russia’s responsibility for crimes against the Ukrainian civilian population. Since the beginning of the invasion, China has provided humanitarian aid to Ukraine worth just €2.3 million (for comparison, Germany alone has provided €370 million).

Political Conditions

The 20th CCP Congress is planned for this autumn during which Xi Jinping is to secure his election as the party’s secretary-general for a third term and nominations will be made for trusted partners to the Central Committee of the CCP. For more than 10 years, Xi’s political agenda has been based on the vision of a rivalry between China and the U.S. It is to be supported by Russia, which also seeks to limit the global influence of the United States. Competition with the U.S. is one of the elements of “Xi Jinping thought”, the political and economic concept enshrined in the CCP’s statute in 2017 and China’s constitution in 2018. Following from this, China seizes the opportunity to verbally attack the U.S., criticising NATO enlargement policy as a cause of the war in Ukraine. At the same time, the Chinese emphasise the importance of cooperation with Russia, expressed, for example, in meetings at the level of the heads of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or in support for Russia’s participation in the G20.

However, China’s cooperation with Russia during the conflict in Ukraine, and the decisive stance of the U.S. and the EU, have worsened the former’s position in relations with Western countries and their partners. China focuses its rhetoric on the responsibility of NATO, and mainly the United States as its lead member, for the outbreak of the conflict by first expanding the Alliance and now supplying arms to Ukraine. This allows the Chinese leadership to strengthen the image in the party apparatus of maintaining a consistent foreign policy and to emphasise the cooperation with Russia as the implementation of Chinese interests. It also gives China the opportunity to present itself in contacts with the Global South or in BRICS as an entity stabilising the international situation. The expression of this perspective was the global security initiative announced by Xi on 21 April in which he stressed the need for the international community to consider the different threat perceptions of individual states, a statement which can also be read as support for the Russian rhetoric. Xi also stressed the importance of the “five principles of peaceful coexistence”, the basis of Chinese foreign policy in the 20th century, also in relation to the non-aligned movement.

China’s policy towards the war in Ukraine is also conditioned by the question of the integration of Taiwan. China is concerned about greater transatlantic unity in the face of Russia’s aggression and the simultaneous strengthening of the U.S. relations with Taiwan and other partners in the Indo-Pacific. Moreover, the Russian experience in Ukraine has made the Chinese authorities aware of the scale of the challenges that the military would have to cope with if China tried to forcibly take control of the island. China’s priority is to eliminate from the debate any comparisons between the question of Ukraine’s sovereignty and the status of Taiwan, as emphasised in March this year by Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister.

Economic Factors

The Chinese authorities oppose the sanctions imposed on Russia, but are reluctant to assist it in circumventing them. They are afraid they could spill over and affect the socio-economic situation in China. Possible secondary sanctions by the U.S. or even EU related to Chinese support for Russia would increase the pre-existing economic problems related to the coronavirus pandemic. These problems are already hindering the promotion of politicians from pro-Xi circles in the elections to the Central Committee. This is especially true of rulers in cities and regions that are not coping well with the pandemic, such as Shanghai (Li Qiang) or Beijing (Cai Qi). Meanwhile, the chances of election of politicians from cities that are better implementing the “zero-COVID” policy, such as Chengdu, Chongqing or Shenzhen, are increasing.

The fear of secondary sanctions also means that cooperation between China and Russia is limited mainly to trade in non-restricted sectors, such as energy. China continues to obtain raw materials from Russia at favourable prices. In March, supplies of coal, crude oil, and copper doubled compared to March 2021. The volume of gas sold to China also increased from January to April this year by over 60% year on year. However, their cooperation mainly takes place through intermediaries (e.g., smaller refineries, forced by Chinese import quotas to obtain raw material fast and from multiple sources), in order not to expose state-owned banks or Chinese companies to secondary sanctions. Their cooperation in the energy sector includes announcements of possible Chinese investments in the Sakhalin-2 gas project, after the withdrawal of Shell. China, however, is cautious about sourcing new supplies of raw materials, mainly due to the destabilised domestic demand. China’s demand for oil in the second quarter of 2022 is expected to decline by 6% compared to 2021. At the same time, most of the Chinese companies on the Russian market have remained, although they have limited the scale of operations. For example, the Union Pay payment system no longer cooperates with Russian Sberbank and Huawei has removed Russian banking applications from its online store. The reduction in the scale of China’s involvement in Russia can be seen in the trade data: in April, exports of Chinese goods fell by more than 25% and were the lowest since May 2020.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The Russian aggression against Ukraine is seen in the CCP as an event that hinders the extension of Xi’s power at the 20th CCP Congress. China’s political support for Russia and careful economic cooperation to avoid secondary sanctions are used by the authorities for domestic purposes. The new global security initiative is also an attempt to strengthen Xi’s image in the party apparatus in the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine and the rivalry between China and the U.S. In the global dimension, it serves only to emphasise the arguments for the reconstruction of the international order, including the weakening of the influence of the West, in line with the interests of China and Russia.

China is currently not ready to intensify the rivalry with a united West, for example, by taking over Taiwan by force. Both the condition of China’s own economy and the potential of its armed forces make that impossible. Moreover, given the tightening of transatlantic cooperation in the context of the war in Ukraine and the long-term U.S. focus on Asian affairs, China might be afraid of future sanctions similar to those on Russia imposed by the West (e.g. in the case of aggression against Taiwan). Therefore, in March Chinese regulators asked financial institutions to conduct stress tests to protect China’s foreign exchange reserves (more than $1 trillion).

From the perspective of the Chinese authorities, the optimal scenario for the war in Ukraine would be an end to military operations that maintains the Russian potential at a level that threatens stability in Europe. This would reduce the risk of sanctions on China for supporting Russia. It also would make it possible to improve economic cooperation with the EU, which is currently hampered by the Union’s announcement that it will shape relations with its partners based on their position on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. The lingering threat from Russia in Europe would engage U.S. attention by limiting its potential in the Indo-Pacific. The longer the Russian regime remains in power, the more it will increase Russia’s susceptibility to China’s economic and political influence. For the EU, this makes it necessary to view Sino-Russian cooperation in its foreign policy as a permanent threat to its interests, as reflected in the virtual EU-China summit in April and suggested by Poland and Germany, among others. This position would apply not only to reducing the economic interdependence of the EU with China but also to combating disinformation from China and Russia.