The Fight for Justice: Ukraine's Legal Steps in Its Defence Against Russian Aggression

Through proceedings before international courts, Ukraine seeks to raise the political cost of the Russian military action on its territory and exert diplomatic pressure to force a cessation of hostilities. It also wants to challenge the controversial legal arguments Russia is using to try to justify the 2022 invasion. While future verdicts may provide a basis for reparations, effective enforcement of rights and punishment of perpetrators of crimes committed on Ukrainian territory are likely to succeed only in the long term. Poland and like-minded states can support Ukraine’s legal position and further assist it in documenting crimes and prosecuting suspects.

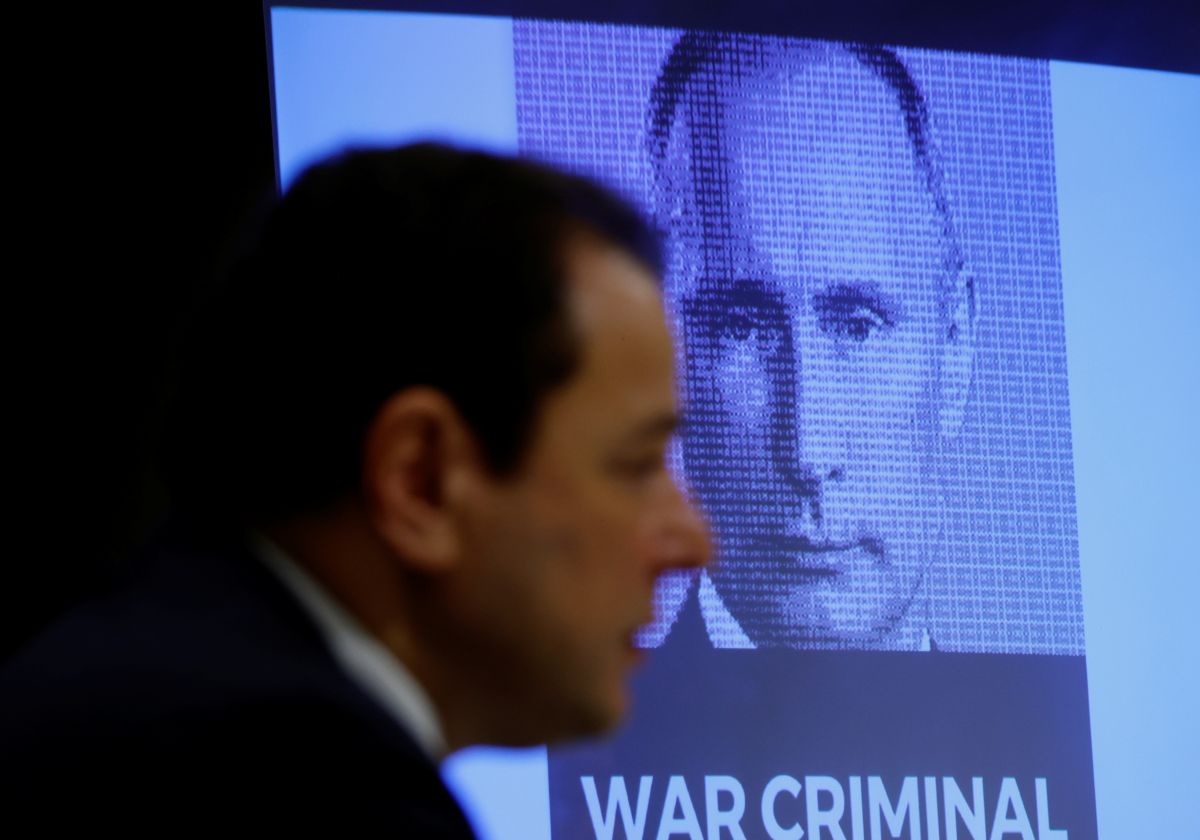

EVA PLEVIER/Reuters/Forum

EVA PLEVIER/Reuters/Forum

Actions before 2022

Ukraine took the first legal action against Russia after the 2014 aggression. It was most active before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). It brought three interstate cases in 2014 alone, and as many as nine in total by the end of 2021 (by comparison, during the first 50 years of the ECtHR’s operation, states had brought only 14). They concerned human rights violations committed by Russia in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, citing infringements of the right to life, prohibition of torture, and freedom of expression, as well as instances of the abduction of children and their transfer to Russia, the death of the passengers of the downed Flight MH-17, and the deprivation of liberty of Ukrainian sailors detained during the Kerch Strait incident.

In addition, in April 2014 Ukraine accepted the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) over crimes committed during the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, and then accepted it indefinitely in September 2015. In this way, although not party to the Court’s Statute, it enabled the ICC to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide committed on Ukrainian territory since the outbreak of the revolution.

Another group of cases concerned the law of the sea. In September 2016, Ukraine initiated arbitration proceedings against Russia within the framework of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) demanding respect for its coastal state rights under the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention in the Black Sea, Sea of Azov, and Kerch Strait. In April 2019, it filed a complaint for the release of its vessels and their crews detained by Russia in the Kerch Strait.

In addition, in January 2017 Ukraine initiated proceedings against Russia before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). It alleged a violation of the 1999 International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism due to Russia’s support with money and arms of the so-called separatists in Donbas. It also accused Russia of violating the 1966 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination through discrimination against the Ukrainian population, including Tatars, in Russian-occupied Crimea. The invocation of these conventions was due to the existence of compulsory judicial settlement clauses in them. Without them, proceedings would have been impossible as they would have required the consent of both parties to the dispute, so also Russia’s.

Results of the Pre-2022 Steps

The effects of Ukraine’s first legal steps up to 2022 were limited. Cases before the ECtHR dragged on, although in the one concerning Crimea and eastern Ukraine the court issued an interim order (which does not prejudge the outcome of the case, but aims to stop the alleged violations pending judgment when there is a risk of serious and irreversible harm). It ordered Russia to refrain from measures violating the rights of Ukraine’s civilian population, notably the right to life and the prohibition of torture, including armed actions. In a case involving Ukrainian sailors, the ECtHR in turn obliged Russia in an interim order to provide them with adequate medical care. In 2021, the court rejected Russia’s formal objections in the Crimea case, paving the way for the final judgment. For Ukraine, it was important that the decision concluded that Russian troops had occupied Crimea militarily and that Russia exercised effective control over it and could thus be held responsible for human rights violations committed there.

The initiation of cases before the ECtHR and PCA may have helped Ukraine to force Russia to release sailors captured during the Kerch Strait incident, which occurred as part of a wider prisoner exchange. Russia also returned detained warships to Ukraine, albeit in an unusable condition. Before the ICJ, Ukraine succeeded in obtaining an interim order requiring Russia to stop discrimination against Ukrainians and Tatars in Crimea; however, this did not improve the situation on the peninsula. In 2019, the ICJ also issued a so-called preliminary ruling, stating that there were no formal obstacles to the consideration of the merits of the case.

Turning to the ICC proved to be of little consequence. The ICC Prosecutor began a preliminary examination of the case, but due to severe financial constraints, caused by low contributions paid by ICC States Parties, the collection of evidence dragged on. As for the law of the sea cases, in one initiated in 2016, the arbitral tribunal concluded in 2020 that it had no jurisdiction over most of Ukraine’s complaints because they were too closely linked to the issue of sovereignty over Crimea, upon which it had no right to decide. However, it did not reject Ukraine’s complaint concerning Russian activity in the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait, and the case is ongoing.

Use of Legal Instruments after the 2022 Aggression

The full-scale Russian military invasion launched on 24 February prompted Ukraine to file new complaints and accelerated the dynamics of some of the pending proceedings. Taking into account the impact so far, the most important cases have been those before the ICJ and the ECtHR. Before the ICJ, Ukraine accused Russia, among other things, of misinterpreting the concept of “genocide”, which the Russian authorities used to justify the invasion by Ukraine in Donbas. It thus took advantage of the mandatory judicial settlement clause in the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which made it possible to file the complaint without Russia’s consent. At the same time, Ukraine requested an interim order directing Russia to immediately halt military action on its territory, which the ICJ granted. Similar orders, albeit narrower in scope, were obtained by Ukraine before the ECtHR. The first one ordered Russia to halt attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure, and the second one to allow the evacuation of civilians to safer areas of Ukraine (rather than transferring them to Russia). However, they were ignored.

The new aggression has also accelerated the ICC’s activities. As early as 28 February, ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan announced that the evidence gathered so far had given rise to the completion of a preliminary examination into the crimes committed in Ukraine, and appealed to States Parties to the ICC Statute to request an investigation, necessary for formal reasons. So far, 43 states (including Poland) have done so. This allowed Khan to launch the investigation on 2 March this year. His office has also taken steps to document new crimes in cooperation with countries involved in the process, including sending the largest investigative team in ICC’s history to Ukraine. Regardless of the ICC’s actions, a group of mainly Western experts and politicians, followed by the Ukrainian government, the EU Parliament, and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, have called for states to set up a new tribunal to try the crimes of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, which the ICC cannot punish for formal reasons. However, other states have so far ignored the idea.

Perspectives

Taking into account the pace of cases filed after 2014, it can be assumed that the proceedings initiated from 2022 onwards will take years. Thus, they probably will be resolved after the cessation of the active phase of military action in Ukraine. Ukraine’s most important success so far should be considered the obtaining of the ICJ interim order ordering Russia to immediately halt military action. This imposes an additional legal obligation on Russia to cease hostilities, and at the same time gives an initial signal that Ukraine’s complaint may be considered on the merits, and could potentially be upheld (an interim order can only be issued if the tribunal considers a violation of the applicant state’s rights at least likely). Further obligations are also imposed by the mentioned ECtHR orders.

However, full enforcement of the orders is unrealistic. The legal acts regulating the operation of the ICJ do not clearly indicate who is responsible for this, but experts usually indicate that it is the competence of the UN Security Council (in which Russia sits with a veto right). In the case of the ECtHR, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe—an organisation from which Russia has been excluded—is responsible for implementing orders, so Russia can hardly be expected to cooperate with it. However, these bodies cannot order coercive measures against Russia anyway due to the lack of enabling legislation. If there are judgments against Russia, it will be difficult to get it to comply without a change in authorities or at least in policy. For the time being, therefore, the judgements of the ECtHR and the ICJ would have mainly a symbolic dimension (especially the ECtHR due to Russia’s expulsion from the Council of Europe), but they also would provide a basis for Ukraine to seek compensation in the future if Russia was to attempt political rapprochement with Western states.

More activity by the ICC Prosecutor’s Office is potentially important. It can act preventively, at least in some cases, by discouraging the commission of new crimes. The problem in enforcing the responsibility of those who have already committed them, however, will be the matter of their arrest and transfer to the court. This is more realistic in the case of rank-and-file soldiers and lower officers. However, at least some ICC States Parties, despite their treaty obligation to prosecute criminals, may shy away from acting against top military and political leaders such as Vladimir Putin or Sergei Lavrov, fearing political consequences. This is all the more important because the ICC cannot pass judgments in absentia, so it will not be able to convict perpetrators unless they are handed over to it. The chances of setting up a tribunal to try the crimes of aggression against Ukraine are moderate, because its success would be largely dependent on the capture of the highest Russian officials responsible for the decision to invade. Hence, it may be difficult to expect stronger state support for this idea.

Conclusions and Recommendations

By using the judicial route, Ukraine is increasing the diplomatic cost of Russia’s expansive policies towards its neighbours and military actions, further undermining their legitimacy and tenuous legal justification. In part, this helps it reduce the disparity in diplomatic potential compared to Russia because the orders imposed on Russia increase pressure to end the conflict and halt actions that violate the rights of civilians. They also make it more difficult for countries politically close to Russia to openly support its actions. At the same time, Ukraine’s use of international jurisdiction demonstrates its commitment to the idea of settling disputes peacefully, contrary to the claims of Russian propaganda, which for years has accused Ukraine of seeking the armed recovery of Crimea and the occupied part of Donbas from Russia. This makes it easier for Ukraine to seek allies.

Poland could support Ukraine by joining, as a third party, the proceedings before the ICJ and the ECtHR, alone or with a group of like-minded countries. It could thus strengthen the legal arguments of the Ukrainian side. In the case of the ICJ, it is necessary to demonstrate a legal interest in resolving the dispute (for Poland this could be, for example, the correct interpretation of the concept of genocide, since the prohibition on preventing, committing and punishing genocide also binds it). Latvia, among others, has announced such an intention. In the case of the ECtHR, the request for intervention requires demonstration that it is “in the interest of the proper administration of justice” (for example, providing a comprehensive assessment of the legal situation to make a correct verdict possible). The courts decide whether to accept the requests; in case of acceptance, they set a time limit for states to present their position.

Poland may also consider supporting the proposal to establish a special tribunal for aggression against Ukraine and getting other like-minded countries to do the same. However, the ICC will be sufficient to investigate and punish the perpetrators of other crimes (war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide), although it seems necessary to increase its funding by the states parties (including Poland). For years it has been too limited in relation to the tasks facing the Court (currently its funding is similar to the budget of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia when it was closing). Poland and other countries can also further support Ukraine in documenting the crimes committed against its inhabitants, for example, by collecting evidence or testimonies from refugees by national law enforcement agencies or other institutions, such as the Pilecki Institute. They can also support the actions of Ukrainian authorities in organisational, equipment and logistic terms, such as the use of joint investigation teams (JIT), like the one established on 28 March.