Strategic Compass: Towards EU Space Strategy for Security and Defence

Although the EU’s flagship space systems are civilian in nature, they are increasingly being used for crisis management or foreign missions and operations. The pursuit of strategic autonomy of the Union, that is the ability to react independently to certain threats, will therefore depend on the development of space technologies. However, further enhancing the EU’s capabilities requires a precise definition of the links between the space sector and security. It also will be crucial for Polish enterprises operating in the space industry that the EU designates priority investment areas where they can benefit.

Fot. Reuters/ European Union, Copernicus Senti/ FORUM

Fot. Reuters/ European Union, Copernicus Senti/ FORUM

EU Space Potential

The European Union is developing two flagship space systems that, in addition to civilian applications, are also used for security purposes. The first is Galileo, a satellite navigation system that provides positioning and timing services. It guarantees better signal coverage (e.g., in cities with tall buildings) and higher timing accuracy than its counterparts—American GPS, Russian Glonass, and Chinese Beidou. In addition, Galileo has restricted-access navigation services, such as Public Regulated Service (PRS, available to government services) and Search and Rescue Service (SAR, for beacons transmitting distress signals), that allow the users to maintain communication and take action in emergencies. Currently, however, Galileo offers limited services and requires additional satellites to be placed in orbit to become fully operational. Parallel to Galileo, the European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS) is also being developed that, by increasing the accuracy of the satellite navigation signal in Europe, allows for planes to make safer landings, among other things.

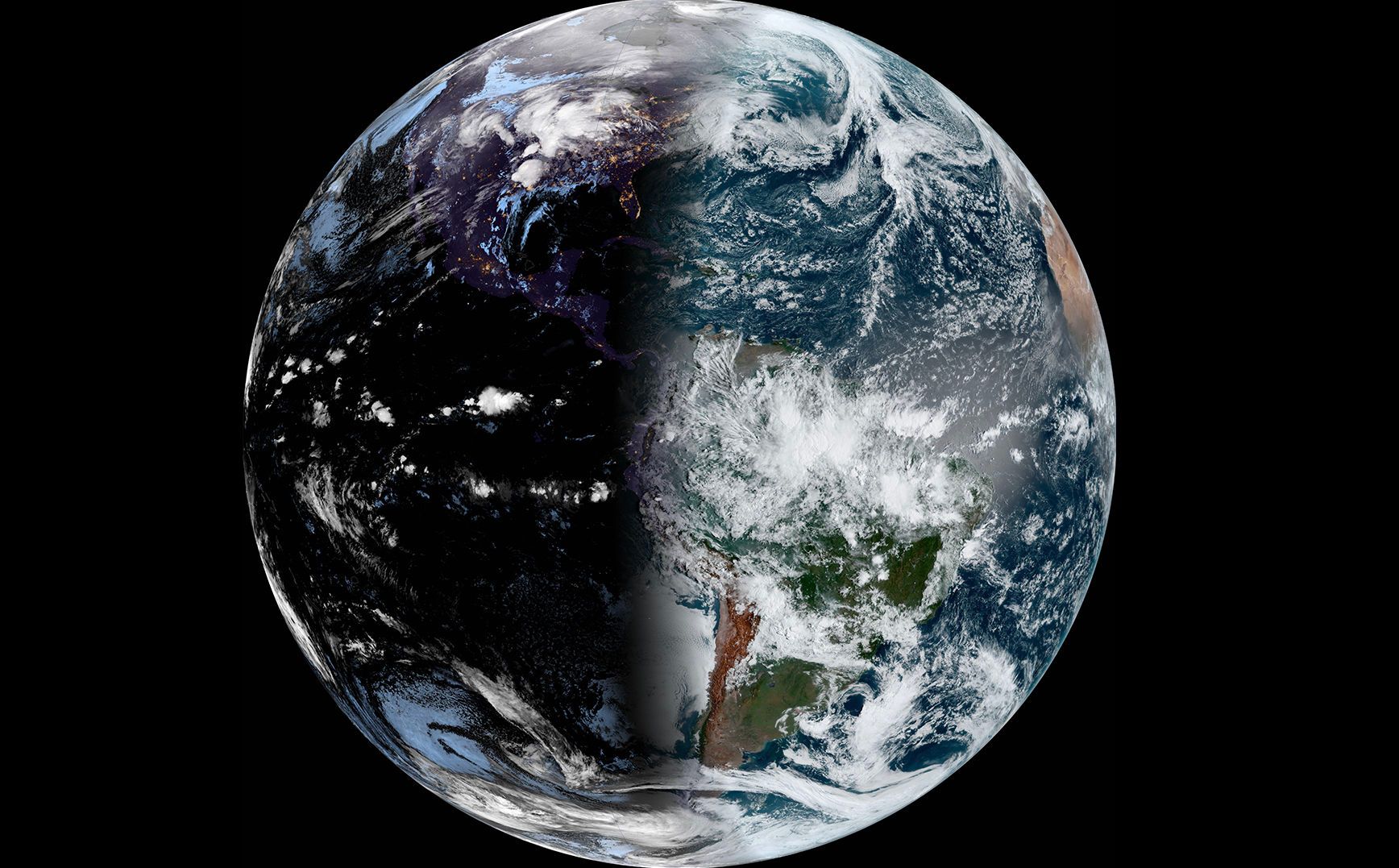

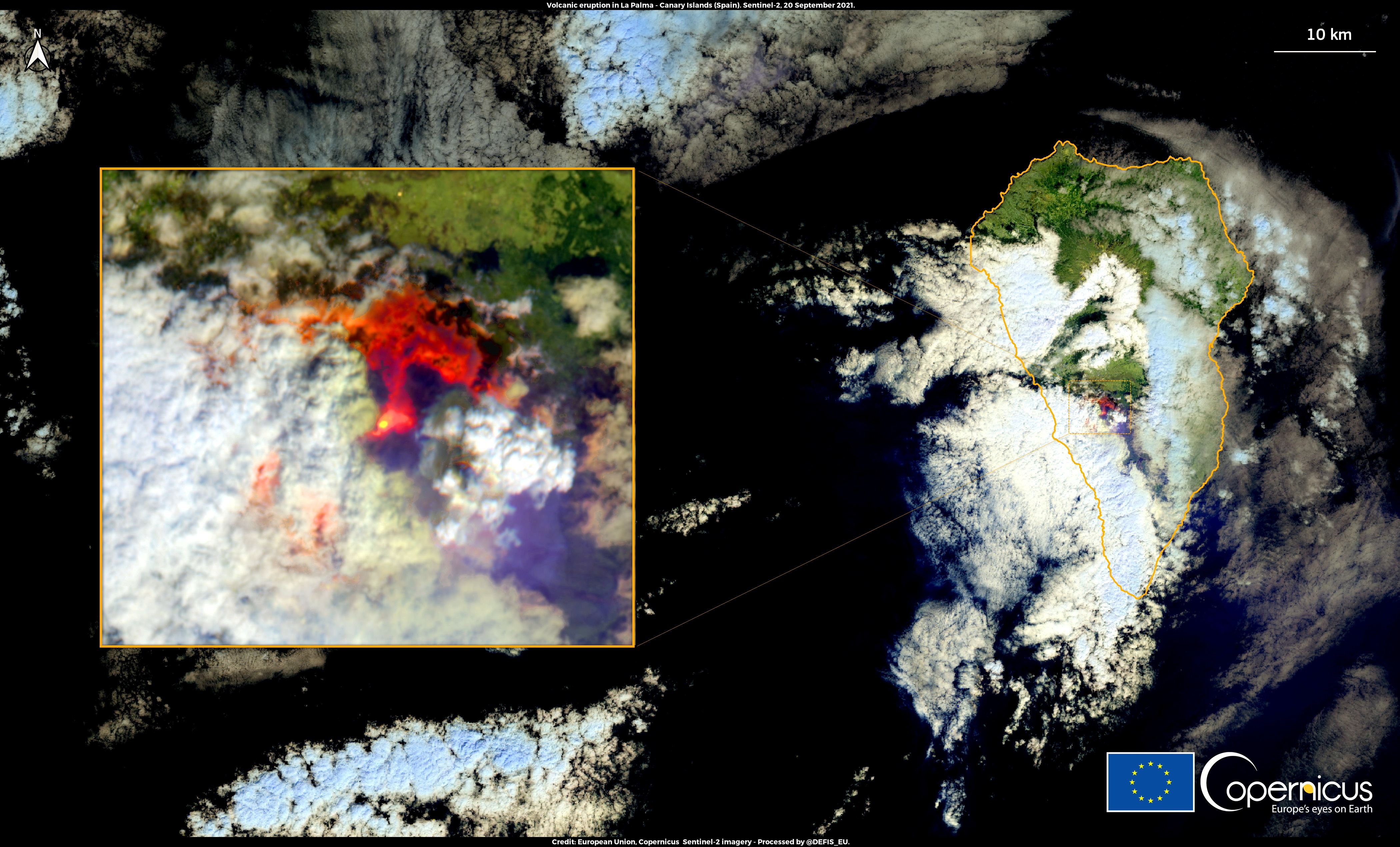

The second is the Copernicus observation system, which allows mapping any area on Earth by combining signals from satellites and sensors on land, sea, and in the air. It creates a wide range of applications enabling, for example, the identification of areas susceptible to the spread of epidemics through environmental factors such as water and air pollution, as well as tracking the effects of climate change based on, for example, changes in sea and ocean levels, and areas covered with vegetation. In addition, it supports actions to protect populations during a crisis by, for example, providing information on areas affected by flood or fire, enabling better management of an evacuation or dispatching emergency services to the right places, among other things. Copernicus maps can also be used for security purposes, for example, as part of intelligence activities, border surveillance, or monitoring of critical infrastructure (power plants, pipelines, etc.).

In addition, within the EU, seven Member States (France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain) are gradually developing the Space Surveillance and Tracking (SST) system, consisting of sensors on the ground and in space. It allows tracking the trajectories of spacecraft and debris, among others, that may pose a collision threat to infrastructure in orbit. In the first half of 2021 alone, there were 7,000 close calls, 190 of which were considered to be high risk. The SST together with Space Weather and Near-Earth Objects monitoring strengthens the Union’s Space Situational Awareness (SSA).

EU Space Sector and Security

The growing importance of space issues in Union policy, as well as their closer link with security, results from the increasing competition between such powers as the U.S., China, and Russia. Along with the appointment of the new European Commission in 2019 and the election of Ursula von der Leyen as president, the Directorate-General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS) was created, responsible for the implementation of the EU Space programme (Copernicus, Galileo, and EGNOS). Despite the search for savings in the 2021-2027 budget due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a significant increase in funding allocated to the space sector (€14.7 billion) and to security and defence (€13.2 billion total, at €4 billion and €8.5 billion, respectively, plus other related spending). The development of the Union’s space sector has also been integrated for the first time into a single space programme, which, given the growing number of projects, is intended to ensure greater coherence and efficiency.

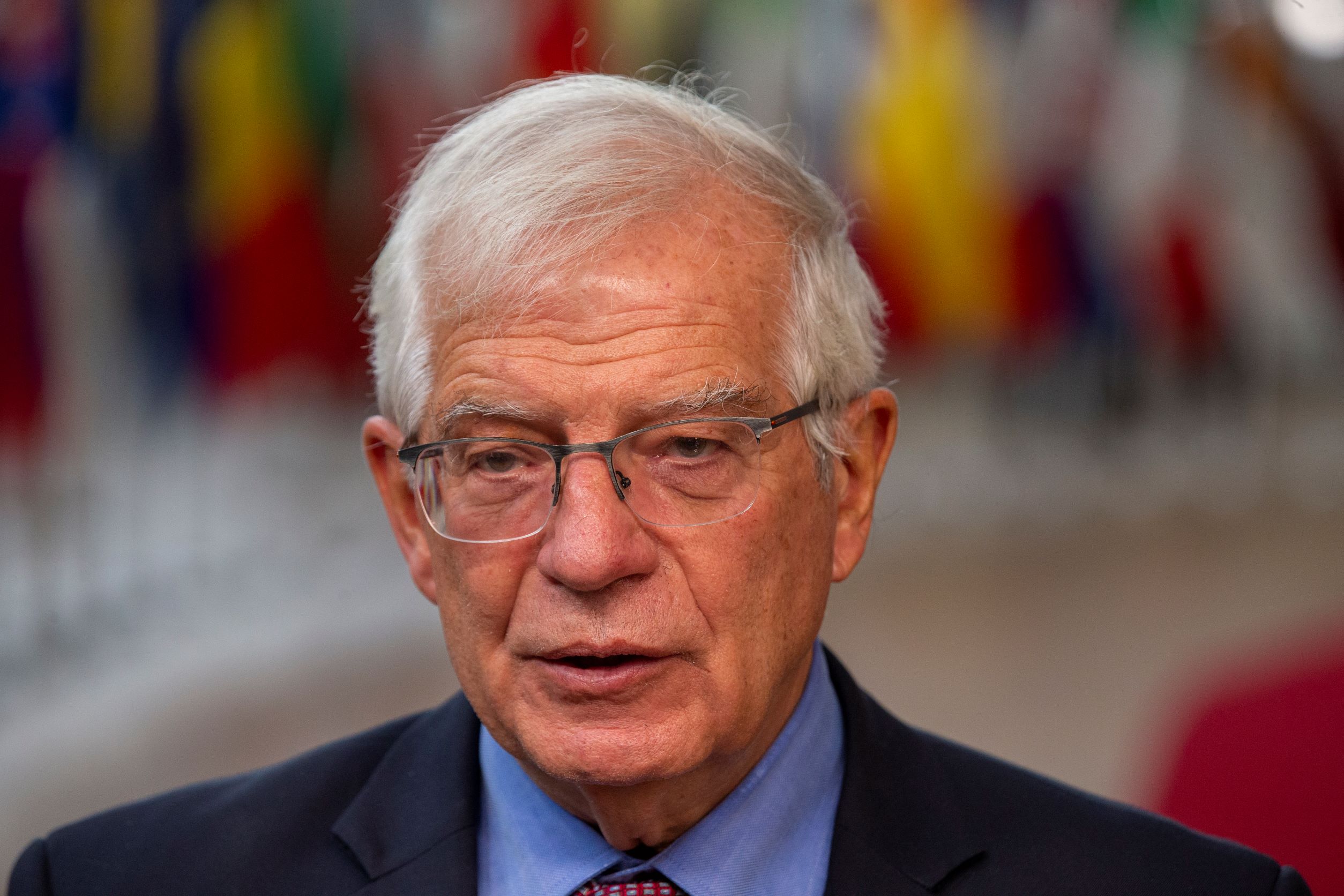

In addition, in 2020, the EU Member States carried out the first Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD), a joint classified check of plans and projects, and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell presented in November 2021 the Strategic Compass, the Union’s security strategy, the final version of which is to be adopted by the Member States in the first half of 2022. The draft version openly indicates the need to link space issues with security, envisaging the development and adoption by the end of 2023 of an EU space strategy for security and defence. Apart from that, there are no detailed public proposals, even though the Compass indicates the space sector as one of the strategic areas for the EU (along with cybersecurity and maritime security). The draft announces only joint exercises and assessment of response mechanisms to space-related threats (Galileo in 2022, then other systems), as well as plans for the development of new technologies to improve space-based Earth observation (including sensors) and the expansion of SSA, although with no specific dates for the time being.

In May 2021, the European Agency for Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GSA) was also succeeded by the EU Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA). Its existing competences in Galileo and EGNOS systems management have been extended to the development of innovations related to them, as well as to the Copernicus system. In addition, the agency took over the responsibility for security accreditation and operational security for all components of the EU space programme and for the implementation of the new Governmental Satellite Communications system (GOVSATCOM).

The Member States have also noticed the importance of the space sector for security, initiating four PESCO projects in this area: 1) establishing a hub for the exchange of classified satellite imagery between Member States and EU entities (COHGI); 2) creating a European military space surveillance network (EU-SSA-N); 3) defence of space assets (DOSA); and 4) developing a radio navigation solution for the development of the Union’s military positioning, navigation, and timing capabilities (EURAS).

Challenges for the EU

Despite the integration of activities under the space programme and advanced flagship space systems, the EU has not yet obtained full autonomy in access to space. The greatest deficiencies are related to launch capabilities at a time when the progressive digitisation of services increases the need for new satellites. In addition, Earth orbits are becoming congested, and sending new objects by states or private entities takes place mostly on a “first come, first served” basis. Therefore, the pace of technology development is key in this case, yet the tests of the first European reusable launch vehicle will not start until 2023. Similar work is also underway in other countries, including the U.S., Russia, China, and India.

Global competition, mainly from private U.S. companies, further increases the need to strengthen the European space sector. In 2021, the EU launched the €1 billion CASSINI space fund to boost the innovation and competitiveness of enterprises. At this stage, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of the initiative, but the overall level of European spending on the space sector is still much lower than the American. For comparison, in 2019 the U.S. allocated $43 billion for this purpose, while the EU and European countries jointly spent just 26% of the American total, $11.5 billion.

Above all, however, the increasing dependence on space systems requires the development of appropriate security measures for existing infrastructure in orbit and Earth-based components that are connected with it. This is particularly important in view of the growing threat of cyber-attacks and the progressing militarisation of space. The latest example of such activities is the unannounced anti-satellite (ASAT) test that Russia carried out in November 2021. By destroying its own satellite, Russia demonstrated its capabilities but also created about 1,500 pieces of debris, posing a threat to other objects in orbit, including the International Space Station (which has Russians on board). No European country has obtained such capabilities so far, but besides Russia, three other countries have ASAT potential, including the U.S., China, and India.

Actions under the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy are also increasingly dependent on the reliable functioning of orbital infrastructure. Since space capabilities translate directly into strengthening security on Earth, their further development based on the needs of users is necessary. In this context, the rapid launch of GOVSATCOM is required, among others, to allow the EU to improve the availability and reliability of communications in crises (e.g., natural disasters) and during foreign missions and operations. The services, often operating in difficult conditions, struggle with the lack of appropriate communication tools. To that end, it will be important to ensure a high level of system security, including resistance to cyberattacks, as well as to standardise the rules and methods of communication between services of the individual Member States and the EU entities. Furthermore, the development of artificial intelligence to connect and analyse datasets is necessary so that end-users responsible for the security of different sectors have faster and easier access to information. The terabytes of data currently collected from satellite systems are not fully exploited.

Conclusions and Recommendations

An ambitious approach to space policy has become essential for the EU and its Member States in order to swiftly detect and respond to external threats. Such capabilities are strategically important because they provide autonomy in decision-making. The details of the common policy should therefore be reflected in the proposed EU space strategy for security and defence.

Despite increasing its investments in the space sector, the EU has limited financial resources at its disposal. Therefore, primarily, a space sector development strategy should be drawn up that will define priority investment directions, as well as set concrete security goals adapted to the risk assessment carried out under CARD. An important element also would be a list of critical technologies, modelled on the classified document developed so far only for Galileo. The further development of EU capabilities in the space sector will therefore depend on a detailed definition of the objectives, which should focus not only on securing systems against attacks (including cyberattacks) and random events but also on faster response to crises, increasing situational awareness during missions and operations, and achieving technological independence. As elements of a space programme are operated by various EU agencies, such as Frontex and the European Maritime Safety Agency, and the Union’s external action is supported by the EU’s Satellite Centre (EU SatCen), it would be advisable to further strengthen the exchange of information and experiences between them, as well as to simplify access to data for EU and Member State services. Pre-emptive actions as part of crisis response should also be expanded by improving the availability and timely delivery of Copernicus imaging.

The EU should also pay more attention to space as an area of operational activities, like NATO (although its document is classified), drawing up specific guidelines for the development of its own capabilities on the one hand, and the procedures and scope of response to adversaries’ capabilities on the other. It is also worth promoting EU initiatives on the international level to prevent the militarisation of space by developing offensive capabilities, simultaneously increasing its defensive and operational capabilities in communication, observation, and intelligence, as well as resistance to potential attack (e.g., Galileo jamming). It would also be advisable to strengthen cooperation with NATO in this regard. However, a significant obstacle is the information exchange between the two organisations—due to its classified nature, such exchange takes place largely through the Member States. Sharing some information from Union systems, such as the SST, with allies, would therefore make a significant contribution to security in Europe. Moreover, there are good examples of EU cooperation with partners, such as work on extending EGNOS to the Eastern Partnership countries. It is also worth it to make active use of the European Space Agency (ESA), whose budget is covered by an EU contribution of 26%. This will allow the EU to maintain cooperation with outside partners, including the UK and Canada. The Union could also be involved in cooperation with partners such as the U.S. in the development of global technical standards and regulations on the methods of space traffic management (STM), which, due to the growing activity of state and non-state entities in space, is becoming an urgent issue.