EU's Strategic Compass Main Assumptions Revealed

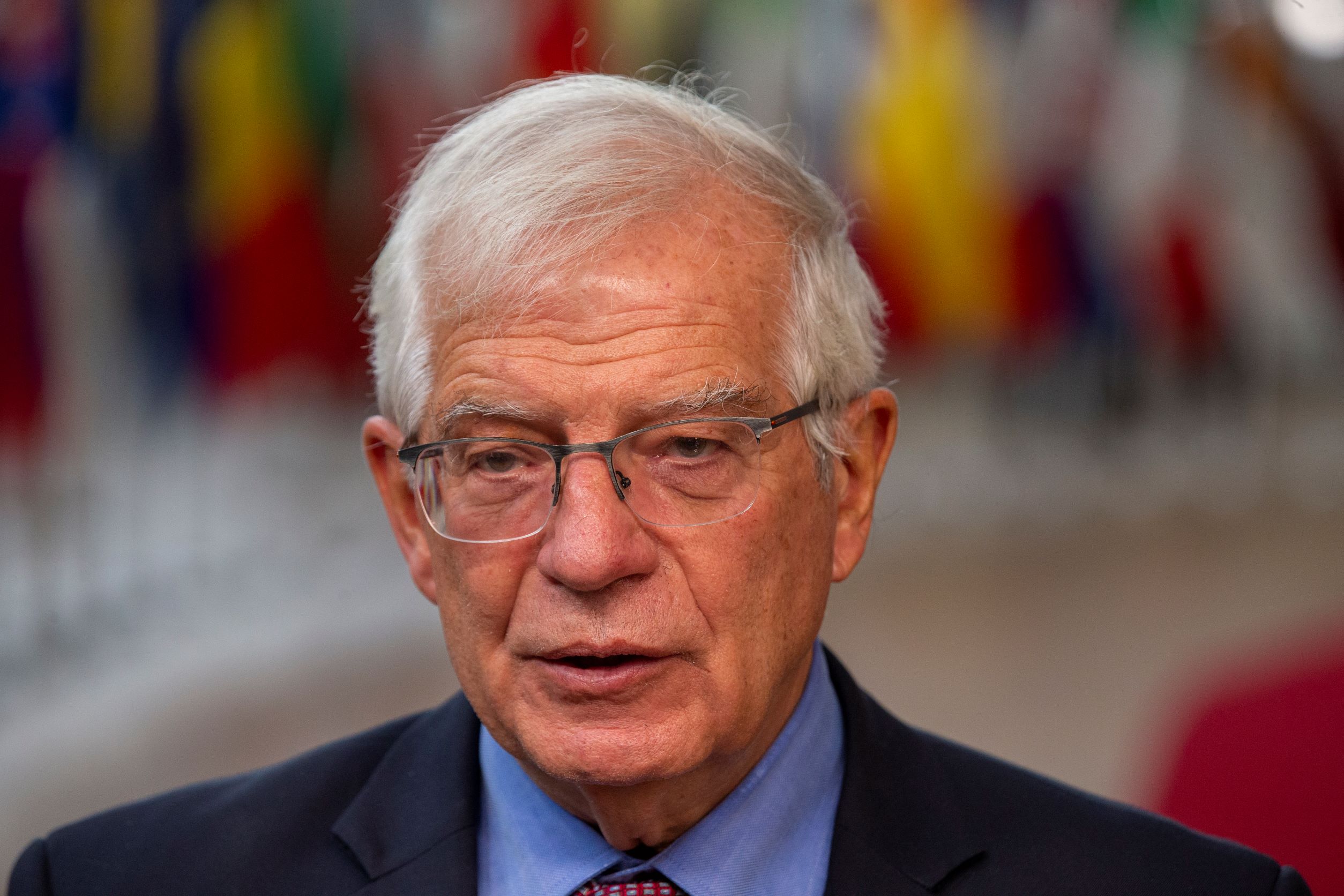

At the 15-16 November Foreign Affairs Council, ministers discussed a first draft of the Strategic Compass, prepared by the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell. According to Borrell and media reports, the document proposes a wide-ranging package of reforms of the EU’s security and defence toolbox. The aim is to reinforce the capacity of the Union to stabilise its neighbourhood and provide security for the Member States. Some proposals, though, may still weaken NATO and generate new tensions in transatlantic relations.

Photo: POOL NICOLAS MAETERLINCK/Belga Press/Forum

Photo: POOL NICOLAS MAETERLINCK/Belga Press/Forum

What is the Strategic Compass and what are the related tasks?

The Strategic Compass is the EU’s most recent reflection process about its level of ambition in the security and defence domain and on the directions of further policies in this area. It was launched in June 2020 on a German proposal and has gone through two phases—the first a risk and threat analysis (November 2020) followed by and an elaboration by the High Representative and based on both results of Phase I and inputs by the Member States—to create a package reforming the EU’s toolkit in the security and defence domain. The first draft of the Compass, discussed by the Foreign Affairs Council at its meeting on 16 November, will now move to inter-governmental negotiations and should be adopted by the Council in March 2022. Implementation of the Compass is meant to increase the EU’s capacity by 2030 to provide improved security to its citizens, better protect its interests and values, stabilise its neighbourhood, and further European defence integration.

How does the Compass assess the EU security environment and its level of ambition?

The draft declares that not only is the EU threatened by the effects of conflict and instability in its neighbourhood but also by direct actions by states and non-state actors through hybrid tactics and innovative technologies. For example, Russia is indicated as a destabilising force in the EU’s neighbourhood, but the draft document does not say it directly threatens the Union but stresses some common Russia-EU interests instead. China is presented simultaneously as a partner, economic competitor, and a systemic rival, which mirrors the language used by the Biden administration. The document considers the U.S. a key EU partner, but deems it to be shifting interest mainly to the Indo-Pacific. Based on these assessments, the Compass repeats the concept that the EU must become ready to shoulder greater responsibility for its own security, acting with partners whenever possible, but also alone, if necessary.

Which ideas may be controversial and why?

The proposal to establish a new rapid reaction force—the EU Rapid Deployment Capability (EURDC)—may become a major source of contention. The groundwork concept, presented by 14 Member States this past spring, was sharply criticised by NATO Eastern Flank states and Sweden. The EURDC would be a 5,000-strong combined force (land, air, maritime components) in a modular form, allowing case-by-case adaptation to a given task, and following the EU’s own training and exercises cycle. While the new force would be based on the existing EU Battle Groups, it would be significantly larger and more expensive, comprising 2,000 land forces troops that would typically take part in one certification drill each year. The EURDC might, consequently, consume resources needed for fulfilling Member States’ commitments to other multinational initiatives, such as NATO Response Forces, or missions and operations. Questions about the viability of the EURDC concept may also arise as the Battle Groups have never been used, so it is not clear why the EURDC would be easier to use. The EU also may not find broad enough support for the concept of finding new, more flexible ways to employ Art. 44 TEU, which provides for a group of willing and able states to run an operation of behalf of the entire Union.

What might the Member States easily agree upon?

Broad support is likely for proposals to strengthen the EU’s capacity to counter hybrid and cyber threats. An “EU Hybrid Toolbox” may be established to link existing instruments to new ones, such as hybrid threat rapid-reaction teams. A new cyberdefence policy may be adopted that would include more robust mechanisms for sanctions in response to cyberattacks (within the “Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox”). There is also common understanding of the need to have the EU do more to stimulate defence-industrial cooperation to develop new weapon systems. This will take strengthen the PESCO mechanism (the Council just adopted another 14 projects, for a total of 60), make better use of the European Defence Fund, and reform the EU’s capability planning. The Member States are also likely to agree to tighten cooperation with NATO, presented in the draft as the EU’s main partner. EU-NATO cooperation may be deepened not only at the technical level but also in the political arena through more frequent meetings of the North Atlantic Council and the EU’s Political and Security Committee on a broadened catalogue of topics.

How may the Compass affect NATO and Poland’s security?

For Poland’s security, it is crucial to increase the military capabilities of the European members of NATO, which should further strengthen Allied defence and deterrence. It may be damaging to that aim if the EURDC force was established in a format that in practice prevented its elements from participation in NATO frameworks. Also, the proposed strengthening of the MPCC command cell (Military Planning and Command Capability) towards a full-fledged operations headquarters, can be considered a bad move. This has been a recurring concept that has been rejected by the EU over concerns about duplication and weakening of NATO structures.

Yet, a more capable EU, ready to engage in military operations is beneficial for Poland’s security. It is also a response to the U.S. calls for taking on more of the defence burden and may increase cohesion in transatlantic relations. For that to happen, though, it will be necessary to develop a mechanism that guarantees that any new EU military capabilities will also be available to NATO. At the same time, if the Compass speeds up the development of EU tools to address hybrid and cyber threats and allows for closer EU-NATO cooperation, it may directly improve Poland’s security.