Scenarios for the EU's Reduction of Economic Dependence on China

China’s economic policy towards the European Union is subordinated to the pursuit of its political goals. Its actions are designed to increase the dependence of the EU’s member states on cooperation with China, thereby expanding its ability to influence these countries and the Union as a whole. The EU's response may follow one of three models: full decoupling, derisking, or inaction. Decoupling involves an almost complete severance of ties with China, which would likely be very costly economically and socially for the Union, and therefore, is currently practically impossible. Derisking is the optimal scenario and involves targeted actions against unfair Chinese practices that threaten the EU in selected sectors. In the passive scenario, i.e., a weakening of the current actions taken on the initiative of the European Commission and some Member States, the EU risks progressive deindustrialisation, which will translate into political destabilisation.

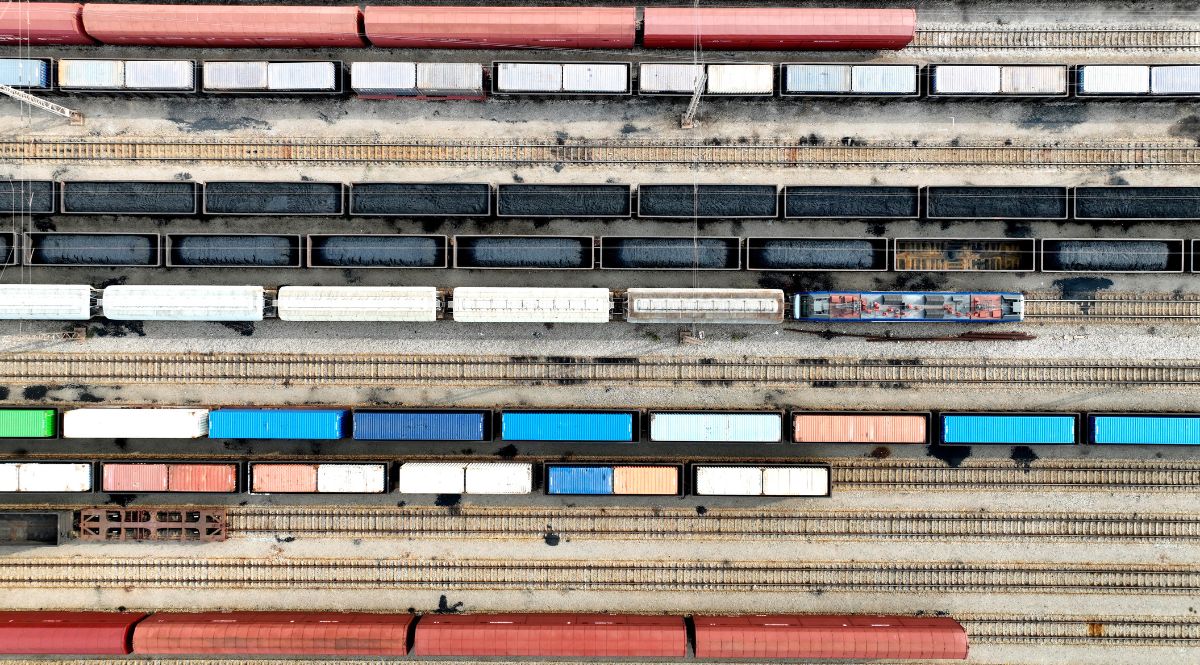

CFOTO / ddp images / Forum

CFOTO / ddp images / Forum

The Deepening Imbalance in EU-China Economic Relations

Since 1997, the EU has recorded a deficit in trade in goods with China, which is a consequence of, among other things, Chinese industrial subsidies. In 2024, the deficit amounted to €304.5 billion (€213.3 billion in exports and €517.8 billion in imports). Between 2014 and 2024, imports from China increased by 101.9%, while exports to China increased by only 47%. This is a long-term trend. According to researchers at the Centre for Economic Policy Research, between 2017 and 2020, access to 240 products in EU member states was fully dependent on foreign imports, of which more than half came from China, 9% from the US, and 7% from Vietnam.[1] The importance of cooperation with China in strategic sectors such as medicine (including active pharmac eutical ingredients—API), defence and technology (as a result of importing processed critical raw materials from China), infrastructure, including energy (Chinese solar panels, wind turbines), electromobility, telecommunications, and logistics (including ports) is also growing. This rapid development of trade relations is a result of the high competitiveness of the Chinese economy and its unprecedented growth in recent decades, but also of the outsized role played by the state in the economy.

China’s non-market practices in its domestic market, mainly the widespread and systematic process of subsidising production, have a negative impact on the EU. In connection with problems in the real estate sector,[2] after 2021, the Chinese authorities decided to redirect financial resources to manufacturing, especially the sectors of cutting-edge technologies, automobiles, chemicals, and industrial machinery, where they are direct competitors of Western countries, especially Germany. At the same time, China is hindering the inflow of imported goods into its domestic market by, among other things, restricting access to the public procurement market, undervaluing the yuan (which increases the cost of imported products on the domestic market) and imposing regulatory barriers. Exports to China are also hampered by state-induced overproduction,[3] which translates not only into increased competitiveness for Chinese companies’ products on foreign markets, but also on the domestic market.

Practices such as production subsidies, closed public procurement markets, and numerous non-tariff barriers lead to a decline in the competitiveness of European countries’ industrial production that is not justified by natural market processes. This leads to an increase in imports from China to the EU, a decline in exports from the EU to the Chinese market, and worsening prospects for EU exports to third-country markets, where they risk being displaced by Chinese products. The result will be an inevitable decline in employment in EU industry, which, according to Eurostat data, accounts for 15.3% of employment in the EU and 19.1% of value added in the economy (excluding the construction sector). This phenomenon is particularly dangerous for Central European countries: the corresponding figures for Poland are 22.3% and 22.9%, for the Czech Republic 26.4% and 26.4%, for Romania 19.8% and 19.3%, and for Germany (Poland’s largest trading partner in exports and imports)—17.5% and 23.4%. Central European countries have the highest share of employment in industry in the entire EU[4].

From Poland’s point of view, its relationships with China as a partner in imports and exports are fundamentally different. China is the second largest source of imports to Poland (14.5% of total imports in 2024[5]). Access to Chinese industrial goods raises the standard of living, and their low prices help to curb inflation. China also has a dominant position in the supply chains of many components and critical raw materials essential to modern industry, and any interruptions in their supply can be costly, leading to temporary drops in production capacity or, in extreme cases, difficulties in accessing key public services. This applies in particular to imports of machinery and mechanical equipment, as well as electronics (both consumer and industrial). At the same time, any precise assessment of the scale of dependence is hampered by re-exports and final processing being carried out outside China (e.g., in Vietnam). As a result, knowledge about the substitutability of specific products is highly technical and therefore can only be found at the individual level of Polish companies using Chinese equipment.

Export relations with China are not of strategic importance for Poland. Any problems related to them will be severe for individual companies and, in the worst case, sectors, but will have little potential to destabilise the Polish economy at the macro level. In 2023, China accounted for only about 1% of Polish direct exports, which is similar to Belarus (0.8%), Russia (1%), and Latvia (0.7%), and significantly lower than Sweden (2.5%), Ukraine (3.2%), or Hungary (2.4%).[6] This level rises to about 3% when we take into account so-called indirect exports, i.e., those related to the participation of Polish companies in international supply chains,[7] especially in German industry. Attempts to hinder exports of Polish products to China would pose a risk for the Chinese side (e.g., in connection with the EU's adoption of the anti-coercion instrument[8]). Due to Chinese efforts to limit imports, there is only limited growth potential for exports to the country from Poland. China also has a small share in Polish exports of individual goods. Among the 10 goods most frequently exported to the PRC, China only has a significant share in total foreign sales from Poland in the case of copper and copper products (approx. 12.5%). Their share in Polish exports of other products is a maximum of around 2%.

Dependence as a Tool of China’s Policy Towards the EU

China’s economic policy towards the European Union is subordinated to its strategic goals. The most important of these is the pursuit of global superpower status and undermining the position of the United States. China uses the EU for both of these goals, although it does not state this explicitly. On the one hand, it seeks to maintain its export opportunities to the EU market, increase the competitiveness of Chinese companies vis-à-vis those from the EU through non-market methods, and to gradually make member states dependent on cooperation with China , especially in the field of modern technologies and critical raw materials. This serves to strengthen China`s global position and maintain stability within the country. It also means that China gains a tool to influence transatlantic relations. Through Europe's economic dependence on China, where the main points of leverage are dependence on imports from the PRC and access to the Chinese market, it may attempt to limit EU cooperation with the United States, both in economic and security contexts.

Economic pressure to coerce political action has been used by China for many years, both in relation to countries and specific companies. It takes various forms, from trade measures (imposing tariffs, introducing export licenses) to government-inspired consumer boycotts, visa restrictions and limitations on tourist arrivals, conditioning of Chinese investments (e.g., on support for the PRC’s policy towards Taiwan), as well as blocking market access in an informal manner (e.g., through administrative practices).[9] Since 2008, China has used economic mechanisms to attempt to exert political influence in its relations with at least 18 countries (including Australia,[10] Lithuania[11]) and over 123 private entities (e.g., Walmart and the NBA).[12] In many of these cases, the action had the desired effect for China, forcing the company or country subjected to these practices to change its stance, e.g., with regard to the sale of products in Taiwan.[13]

Of particular importance to the European Union were the restrictions on the export of rare earth metals[14] introduced in April 2025 by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce in response to the US decision to impose ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on China.[15] At that time, they introduced the obligation for each importer to obtain a license from the Chinese authorities to import seven elements from the country. Although the Chinese authorities initially claimed that the EU was not the main target of these regulations, this has not yet translated into, for example, exempting the EU from this regime and permitting the unrestricted export of rare earths. Furthermore, in October this year, China presented new regulations on rare earth metals. The list was expanded to include five more elements. A requirement was also introduced to obtain a license for the further sale of any foreign manufacturer’s product containing even 0.1% of metal originating in China. Following negotiations with the US, after Xi Jinping met with Donald Trump on October 30 this year, the applicability of these regulations was suspended for one year. After negotiations involving the EC and the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, the procedures were temporarily accelerated, but they continue to have a negative impact on EU companies. In September 2025, the European Chamber of Commerce in China indicated that of the 140 companies that had sought its support in the licensing process since April 2025, only a quarter had so far obtained approval from the Chinese.[16] In addition, the requirements for importing these substances allow China to obtain information about the technological processes of foreign companies, which increases the competitiveness of entities from China. The suspension, acceleration, and subsequent re-delay of the licensing process indicates that the Chinese authorities’ actions are not solely due to bureaucratic problems or staff shortages at the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (offered as justification by the Chinese authorities), but are also politically motivated. They are a test of the potential impact on the EU in ongoing trade negotiations, e.g., regarding tariffs on electric vehicles or the conditions for Chinese companies operating in the EU market. Making changes to the procedure for obtaining critical minerals contingent on concessions from the EU was suggested, among others, by the Chinese Minister of Commerce during negotiations with the EC.

The exploitation of dependencies affecting the condition of EU companies, production capacities, and the functioning of infrastructure[17] can be used to support political circles advocating closer ties with China.[18] In combination with Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) operations, this allows the Chinese authorities to influence how European societies perceive certain decisions in domestic or foreign policy, e.g., with regard to support for Ukraine or relations with Taiwan. This, in turn, helps gain support from political circles in the EU that are favourable to the development of relations with China, both bilaterally and within the EU.

These dependencies may influence the approach and assessments of EU countries on issues important for European security, such as Chinese-Russian relations or transatlantic cooperation. The high level of dependence is attributed as the main reason for the inaction of certain political circles and EU countries. Understanding the threats to European security posed by Chinese policies does not translate into decisive decisions that could more strongly restrict the activities of China and Chinese companies on the European market.

The Impact of the US-China Rivalry on Reducing EU Dependence on China

EU-China relations, both economic and political, are developing against the backdrop of intensifying Sino-American rivalry. Due to their similar levels of economic development, the US faces similar challenges in its relations with China to those faced by the EU—erosion of the competitiveness of domestic industry, a growing dependence on imports from China, intellectual property rights violations, and threats to its comparative advantage in the field of modern technologies. However, many negative phenomena occurred in the US much earlier, in the first decade of the 21st century, mainly as a result of China’s accession to the WTO. The rapid growth of imports from China led to the collapse of entire industrial sectors and, as a consequence, to negative social effects and growing political polarisation. Therefore, Donald Trump’s first administration in 2017–2021 took measures to limit the negative effects of relations with China, especially by raising tariffs. These measures were maintained by Joe Biden's administration (2021–2025), but they were only partially effective. They contributed to a reduction in the US bilateral trade deficit with China from a record $539 billion in 2018 to $439 billion in 2024, but this was accompanied by an increase in imports from other countries, including those strongly integrated into Chinese supply chains. This means that a decline in direct imports from China does not necessarily lead to a real rebalancing of trade relations, which are largely driven by the internal economic policies of the partners.[19]

Economic rivalry between the US and China intensified after the inauguration of Trump’s second administration, escalating to a trade war in April this year. After “Liberation Day” and the imposition of tariffs on all trading partners by the US authorities, China responded by raising tariffs on US goods, which led to a tit-for-tat increase. Currently, the average tariff remains at around 15.8%.[20] However, given that the actions of the current US administration are aimed at fundamental changes in the global trading system and the replacement of “free trade” with “fair trade,”[21] the current situation cannot be considered stable, both in terms of US-China relations and US relations with other trading partners, including the EU. Attempting to rapidly adjust the economies of the US's trading partners (i.e., virtually all countries in the world) to the new realities may lead to negative economic consequences, such as an economic slowdown and, potentially, economic crises caused by a loss of competitiveness of certain sectors and companies as a result of changes in tariff policy, and ultimately, political instability. Both the EU and China will therefore face a choice between attempting to manage their problems internally and continuing negotiations with the US as a key export partner for both. On the Chinese side, this also means extensive efforts to reduce China`s dependence on the US and the EU in terms of both technology and access to markets.

Existing EU-China dependencies also have a direct impact on the decisions of member states and EU institutions regarding relations with the U.S. Uncertainty about US policy towards the PRC, as well as the Trump administration’s trade policy decisions negatively affecting the European Union, further hamper transatlantic cooperation. The belief that forming a common policy vis-à-vis China could become a unifying factor in transatlantic relations (despite many problems in bilateral relations) currently exists mainly at the rhetorical and expert level. Its implementation is less likely, not only because of the level of EU countries’ dependence on China and the challenges for economies associated with reducing it, but also because of the EU’s distrust of the Trump administration and the prospects for the development of rivalry between China and the US.

The context of US security guarantees against threats from Russia, which is particularly important for countries on NATO’s eastern flank, further reinforces the uncertainty of EU countries regarding US policy. The US’s determination and commitment to honouring its obligations may be threatened in the context of growing isolationist tendencies (including within the US Department of War). From the perspective of Poland and the EU, this is another argument for accelerating the reduction of dependence on China, which currently increases vulnerability to threats resulting from China’s strategic cooperation with Russia. In a radical but potentially possible scenario of the US focusing entirely on domestic issues, with minimal military presence in Europe and moderate involvement in the Indo-Pacific (limited only to formal allies), Sino-Russian relations and Europe’s dependence on Chinese manufacturing imports would be important determinants of the EU’s defence policy.

Possible Scenarios

In a situation of high dependence (especially in the area of critical infrastructure or strategic sectors), the EU has three courses of action to choose from. The first (the passive scenario) assumes the continuation of the current model of economic cooperation with China, and even its further deepening along the present lines, especially in sectors where member states and major companies see no alternative. The second scenario is decoupling, which means a radical break in cooperation and striving for a minimal presence of entities from China on the EU market. The third scenario, active derisking, suggests strengthening current processes, reducing dependence on China in critical and strategic sectors, while continuing cooperation where it does not pose a threat.

Passive Scenario—Continuation of Relations According to the Current Model

Key elements. The passive scenario involves refraining from the introduction of new trade measures against China’s harmful actions and even withdrawing or limiting those already in place. In this scenario, short-term economic efficiency prospects, according to which almost all measures interfering with free trade are considered disadvantageous, are paramount. The introduction of restrictions on imports from China and their possible retaliatory measures (whose potential in relation to Poland is limited, according to trade statistics) will therefore cause difficulties for individual companies and sectors. As a result, some EU countries (e.g., Germany and Hungary, which voted against imposing definitive countervailing duties on Chinese electric cars[22]) remain reluctant to pursue a policy of actively counteracting dependence on China. Given the non-market practices in the Chinese economy, arguments about commitment to the free market, both from China and European countries, should be considered purely rhetorical.

Possible consequences. The most important consequence of adopting a passive stance will be the potential collapse of industrial sectors in the E U as a result of increased exposure to trade with China,[23] which will translate into far-reaching social and, ultimately, political consequences. An example of such development is the decline in industrial employment in the US following China’s accession to the WTO (from around 17 million in 2000 to around 13 million today), which has caused grave social difficulties. The symptoms of the negative consequences of adopting a passive approach are already visible in the EU. According to the European Trade Union Confederation, industrial employment in the EU fell by 2.3 million jobs between 2009 and 2024, including 1 million between 2019 and 2024. Industrial production in the Eurozone has fallen by around 2% and by 0.8% across the EU since 2021. Due to high energy prices, entire industrial sectors in the EU are losing competitiveness against subsidised Chinese industry. In 2024, Volkswagen considered closing factories in Germany (which was avoided, although large-scale layoffs are still to take place). Bosch and automotive parts manufacturers Schaeffler Group and Valeo also reduced employment in Europe. In February 2025, the Audi factory in Brussels was closed. In a passive scenario, these phenomena will intensify, as was the case, for example, in the solar panel sector, which has been completely dominated by products from China.

Growing public frustration is leading to, among other things, increased polarisation and a conservative shift in political preferences.[24] The consequences of increased competition from China are already visible in Western Europe, where support for extreme parties, especially right-wing ones, is growing in declining industrial regions. Research indicates that such patterns can be observed in at least 15 EU countries and were already visible in the period 1988–2007. The distribution of the benefits of globalisation is considered unfair by some constituents—primarily employees of companies losing competitiveness, whose jobs are threatened, and residents of regions particularly affected by socio-economic problems. In the absence of sufficient compensation for the sensitive groups, their preferences tend to shift towards protectionism and isolationism, often combined with authoritarian and anti-minority tendencies.[25] These effects are not immediate, but they are noticeable and likely to be long-lasting.[26] Widespread opposition to supranational economic integration and globalisation may become a factor which threatens the future of the European integration project in its current form.

Radical Scenario—Full Decoupling

Key elements. The premise of the decoupling policy is (at least in theory) the need to sever all economic ties with China. Such a step would be justified by a high awareness of the threats to the economy and military security posed by close economic cooperation with China, especially in critical sectors. This process would require the EC to play a key role as the institution crucial for the development of the EU trade policy. In practice, it would have to involve the imposition of high tariffs—either horizontal or targeted at specific sectors, as was the case with electric vehicles.[27] It would be necessary to significantly intensify the use of trade instruments and other tools aimed primarily at China. This applies both to proceedings related to Chinese subsidies (FSR and, in case of unfounded application of countermeasures by China, the anti-coercion instrument)[28] and to the exclusion of Chinese entities from the public procurement market (at the level of the EU as a whole, individual Member States, or even particular contracting authorities)[29]. The latter was applied by the EC to Chinese medical equipment manufacturers in response to China’s blockade of European manufacturers in this sector. The decoupling scenario would require the gradual implementation of further instruments, with the European Commission playing a leading role. It would be likely that a mechanism for screening investments from China (also using the FSR) would be developed, and that work on outward investments screening would be finalised. In this scenario, it would be necessary to adopt decisive regulatory solutions, e.g., excluding suppliers from China from the telecommunications sector, a ban on the movement of electric vehicles with Chinese software (which could be used to collect sensitive data) in strategic locations, or a ban on the use of equipment from China in energy installations above 100 kW, i.e., a level that has a significant impact on the operation of the energy system (such a decision has already been taken by Lithuania, for example). It would be advisable to increase the enforceability of penalties imposed on Chinese entities, such as ByteDance (the owner of TikTok), for violating EU law imposing obligations on social media. This process and its gradual extension to other entities would ultimately aim to bring about the cessation of their operations in the EU.

To implement this strategy, it would be necessary to accelerate the development of the EU’s industrial base, which would require protective measures in the form of tariffs and increasing the ambition of industrial policy at the national and EU levels.[30] The EU’s biggest economic competitors, the US and China, use state aid on a large scale. In recent years, EU Member States have also been permitted to grant such aid with less stringent restrictions, due to the relaxation of EU rules during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additional investment would be needed in projects involving the extraction and processing of rare earth metals in the EU and in third countries—both in the immediate vicinity, e.g. Ukraine, and in developing countries in Asia,[31] Africa,[32] and South America.[33] Modifying the Green Deal, mainly in terms of the deadlines for increasing the role of renewable energy, would further reduce dependence on China. The costs of projects aimed at increasing the competitiveness of EU industry were estimated at around €800 billion per year, or almost 5% of the EU’s GDP in Mario Draghi’s report.[34] In a situation of rapid decoupling from China, investments of a similar scale would be necessary to replace Chinese products on the EU market.

Possible consequences. Full decoupling would require large-scale investment in the EU economy, for which the EU is unlikely to be able to muster financial means quickly. According to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, eliminating bilateral trade with China would caus e a permanent reduction in real income in the European Union of 0.8%. The same institute estimated that for Germany, this would mean a 5% reduction in GDP in the short term, while in the long term the decline would be 1.5%.

A radical reduction of economic ties with China would have significant socio-economic consequences for the EU, which could lead to political destabilisation. The implementation of this scenario in the short term could lead to social tensions and further strengthen radical political movements. In the event of decoupling in the EU, inflation would inevitably rise, and access to key goods (antibiotics, electronics, and a range of dual-use goods important for defence development) would be hampered. This would have a negative impact on the economic growth across the Union and could even trigger a recession. Positive consequences (e.g., in the form of the EU’s reindustrialisation) would only materialise after a few years. The decoupling scenario would generate high short-term costs for selected sectors. For example, in telecommunications infrastructure in the EU, removal of Chinese operators from the 4G network would lead to an estimated cost of around €3.5 billion,[35] and TikTok’s contribution to the GDP of Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and France in 2023 was just below €5 billion.[36] It is very difficult to precisely identify or even estimate the total cost of reorganising supply chains at the EU level due to the complexity of the linkage both within and outside the Union.

Moderate Scenario—Tightening of Derisking Policy

Key elements. This scenario assumes the consistent and effective implementation of the derisking policy towards China that has been followed by the EU for several years. The aim of this scenario is to regulate the presence of Chinese entities in the single market at both the EU and Member State levels.

The policy of derisking continues to be controversial and creates divisions among member states. However, discussions within the EU are not about the idea of derisking itself, but about its specific aspects and the scope of application of available measures or the creation of new ones. One of the most important dividing lines is the extent of the EC’s interference in areas that member states consider to be their competences. So far, the EU’s most important achievement in this policy has been the introduction of countervailing duties on Chinese electric cars ranging from 17% to 35.3%, and the EC is technically ready to take further action against Chinese subsidies. In 2024–2025, on the basis of the Foreign Subsidies Regulation, it conducted several dozen such investigations, including against Chinese manufacturers of solar panels and locomotives. As in the decoupling policy, this scenario also requires the EC to use a range of offensive and defensive instruments relating to subsidies,[37] public procurement,[38] and screening of investments from the PRC.

As part of these instruments, the EC has already introduced (using the regulation on international public procurement[39]) countermeasures against Chinese practices in the medical device market.[40] It has also imposed countervailing duties on plywood and launched an investigation into subsidies in the tyre sector. In the near future, however, this policy should be complemented by broader measures in the area of supply chains (e.g., developing partnerships with friendly countries, increasing local production and stock levels), tightening investment controls, and pursuing a more ambitious industrial policy.

It is advisable for the European Commission and Member States to take action, not to eliminate Chinese entities from all sectors, as in the decoupling scenario, which would be too costly economically and socially, but rather to significantly reduce or sever cooperation with China in sectors critical to EU security. This would lead to an increase in the competitiveness of EU industry and gains in terms of security, including by eliminating Chinese companies from critical and strategic infrastructure sectors.

Possible consequences. According to Eurostat, industry in the EU accounts for a larger share of value added than employment, which means that maintaining jobs in industry is beneficial for the economy. Effectively implemented derisking will slow down the erosion of the EU’s industrial base, but only in selected sectors. It is therefore necessary to apply it to cutting-edge industries (e.g., automotive, renewable energy, robotics, advanced semiconductors) and those that create the most jobs proportionally: metals production (approx. 12% of industrial employment), machinery (approx. 10%), rubber and plastics (approx. 5%), and chemicals and electronics (approx. 4% each). The costs for the EU budget and Member States will depend on specific solutions, but in the medium and long term, an extensive derisking policy should bring economic benefits or at least allow the Union to avoid the negative consequences of a passive scenario.

Conclusions and Recommendations for the EU and Poland

In the coming years, foreign economic policy will focus on security issues, limiting potential losses, and managing negative processes. As such, it will be suboptimal from the point of view of short-term market efficiency. However, the global economy is currently heavily dependent on Chinese industrial policy, which is incompatible with free market principles and has a negative impact on China’s trading partners. Economic reform in China, which could significantly reduce its negative impact on the economies of its trading partners, is unlikely for political reasons. This is because reforms would mean the Chinese Communist Party giving up some of its instruments of power and control over the party apparatus and society. One solution is for major players such as the US and the EU to move away from the current approach to international trade, based on the model of “free trade” and liberalisation of exchange. This year, the United States has done so in a radical way. The increase in tensions in international politics, especially between the U.S and China, indicates that the development of a new stable, multilateral, and mutually beneficial global trading system is unlikely in the near future. The EU will be forced to take unilateral action both towards the US and China, and boldly use its economic assets in its relations with them (sources of chip manufacturing technology, a large market, a developed and still competitive industry in some areas), without which it may be impossible to maintain its international position and the standard of living of its citizens.

For Poland and the EU, the optimal choice is a moderate model, i.e., intensified derisking. Current EU actions in this area are heading in the right direction, but are likely insufficient. From Poland’s point of view, it is advisable to support efforts to tighten them and, in the event of negative consequences, to compensate for losses incurred by affected countries and regions (e.g., due to China’s response) and social groups that are particularly vulnerable, e.g., to rising inflation. Regardless of the policy pursued, the introduction of measures will be necessary due to the negative effects on the EU economy resulting from China’s policy of reducing its dependence on the EU, closing strategic sectors to cooperation with the West, and taking over markets while gaining often artificial (e.g., due to subsidies) competitive advantages, as happened in the automotive sector. It is advisable to make wider use not only of defensive trade measures, but also of active industrial policy, including state aid, to support sectors considered critical. Such measures could be part of negotiations within the EU and with its partners (including the US) as part of discussions on tightening policy towards China. It is worth considering the introduction of protective measures for the entire EU industry as a means of putting pressure on the PRC to increase the chances of reforming the Chinese subsidy system. The instruments used by the EU should also exploit the PRC’s dependence on the EU for imports. In 2022, China’s dependence on imports from the 27 individual member states concerned 33 different product groups, or an average of 1.2 per country. These included, for example, lithographic machines for the manufacture of semiconductors from the Netherlands. However, if we consider the EU as a trading bloc, the number of such products rose to 120[41]. The active derisking scenario is also the most optimal solution due to its positive impact on the development of the EU’s defence capabilities, including its production capacity. This is particularly important in the context of the threats posed by Russia’s aggressive foreign policy and its cooperation with China.

[1] R. Arjona, W.C. Garcia, C. Hergheleqiu, “The EU’s strategic dependencies unveiled,” Center for Economic Policy Research, 23 maja 2023 r., https://cepr.org.

[2] For years, real estate construction and trading, as well as the boom in this market, were an important element of GDP growth, including local government revenues. In recent years, however, demand has fallen sharply, which has translated into problems for development companies and, consequently, the financial situation of local authorities. See: P. Dzierżanowski, D. Wnukowski, “China’s Economic Problems Worsen: The Domestic and International Aspects,” PISM Bulletin, no. 125 (2244), 8 September 2023, www.pism.pl.

[3] Overproduction in China is the result of the current economic model, which involves the artificial, subsidised expansion of specific industries by supporting the creation of companies in a given sector whose production cannot be consumed by the domestic market and must be exported abroad. See: P. Dzierżanowski, “China Resists Correcting Unbalanced Economy, Risking the Future of International Trade,” PISM Bulletin, no. 186 (2494), 12 December 2024, www.pism.pl.

[4] “Gross value added and income by main industry (NACE Rev. 2 ),” Eurostat, 30 July 2025, https://ec.europa.eu.

[5] “Foreign trade turnover of goods in total and by countries (final data) in 2024,” Statistics Poland, 30 July 2025, https://stat.gov.pl/en.

[6] Yearbook of Foreign Trade Statistics 2024, Statistics Poland, 31 October 2024, https://stat.gov.pl/en.

[7] M. Šebeňa, T. Chan, M. Šimalčík, The China factor: Economic exposures and security implications in an interdependent world, CEIAS Papers, 30 March 2023, https://ceias.eu.

[8] Which allows for a response to attempts to use economic coercion against Member States by introducing retaliatory measures at the EU level.

[9] M. Szczepański, “China’s economic coercion: Evolution, characteristics and countermeasures,” European Parliament Research Service, November 2022, www.europarl.europa.eu; J. Mullinax, “China’s New Economic Coercion Toolkit,” The Diplomat, 22 March 2025, www.thediplomat.com.

[10] This was in response to Australia’s proposal to investigate the causes of the COVID-19 pandemic.

[11] In response to Lithuania’s approval of the opening of a Taiwanese representative office in Vilnius in 2021.

[12] “Examining China’s Coercive Economic Tactics: Congressional Testimony by Victor Cha,” CSIS, 10 May 2023, www.csis.com.

[13] In 2018, under pressure from the PRC, three US airlines changed their reservation systems. Instead of the previous destination name “Taiwan,” they introduced the phrase “Taiwan, China.”

[14] Earlier, in 2023, the Chinese authorities had also imposed restrictions on the export of gallium and germanium.

[15] P. Dzierżanowski, “China-U.S. Trade War Intensifies,” PISM Spotlight, no. 26/2025, 9 April 2025, www.pism.pl.

[16] J. Leahy, “EU companies hit by renewed delays to Chinese rare earths licenses,” Financial Times, 17 September 2025, www.ft.com.

[17] That is, both economic and security issues of individual regions or member states.

[18] The practice of “elite capture” is difficult to identify unequivocally. China’s actions in this regard are corroborated by, among other things, corruption cases in the European Parliament and accusations of espionage against individuals associated with politicians in the United Kingdom and Germany. J. Rankin, “Several people arrested in EU bribery investigation linked to Huawei,” The Guardian, 13 March 2025, www.theguardian.com; “The controversy over the collapsed China spy case explained,” BBC, 14 October 2025, www.bbc.com; K. Conolly, “AfD politician’s former aide convicted for spying for China,” 30 September 2025, www.theguardian.com.

[19] P. Dzierżanowski, “The U.S.-China Rivalry is Changing International Supply Chains,” PISM Bulletin, no. 143 (2262), 11 October 2023, www.pism.pl.

[20] “US Tariffs: What’s the Impact on global trade and the economy?,” J.P. Morgan Global Research, 30 October 2025, www.jpmorgan.com.

[21] P. Dzierżanowski, “U.S. Policy Shifting from Free Trade to ‘Fair Trade’,” PISM Bulletin, no. 35 (2536), 18 March 2025, www.pism.pl.

[22] J. Szczudlik, “In Landmark Decision, EU to Impose Definitive Tariffs on Chinese EVs,” PISM Spotlight, no. 64/2024, 4 October 2024, www.pism.pl.

[23] Although this is not the only cause of the difficulties faced by industrial regions, the experience of the US shows that competition from products from the PRC is an independent factor causing economic, social, and political consequences that are more profound than in regions that are not exposed to it and also experience other phenomena, such as production automation.

[24] D. Autor, D. Dorn, G. Hanson, K. Majlesi, “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 110, No. 10, 2020, pp. 3139–3183, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20170011.

[25] I. Colantone, P. Stanig, “The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 62, No. 4, 2018, pp. 936–953, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12358.

[26] A. Backes, S. Mueller, “Import shocks and voting behavior in Europe revisited,” European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 83, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpe.2024.102528.

[27] J. Szczudlik, op. cit.

[28] Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR); Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI).

[29] International Procurement Instrument (IPI) – regulation on access to public procurement markets of Member States.

[30] P. Dzierżanowski, S. Zaręba, “EU Industrial Policy: Instruments Available at the National and EU Levels,” PISM Bulletin, no. 3 (2311), 12 January 2024, www.pism.pl.

[31] P. Dzierżanowski, D. Wnukowski, “EU Looks to ASEAN Countries for Critical Raw Materials Supplies,” PISM Bulletin, no. 109 (2417), 23 July 2024, www.pism.pl.

[32] D. Kopiński, African critical raw materials and the economic security of the European Union, Warsaw: Polish Economic Institute, August 2023, https://pie.net.pl.

[33] K. Sierocińska, B. Michalski, Latin America’s critical raw materials and the economic security of the European Union, Warsaw: Polish Economic Institute, June 2024, https://pie.net.pl.

[34] “The Draghi report on EU competitiveness,” European Commission, September 2024, https://commission.europa.eu.

[35] “The real cost to rip and replace Chinese equipment from telecom networks around the world,” Strand Consult Research Note, 20 February 2025, https://strandconsult.dk.

[36] C. Warner, E. Heaton, M. Vickers, “The Tik-Tok effect: the socioeconomic impact of TikTok in five European countries,” Oxford Economics, 12 January 2024, www.oxfordeconomics.com.

[37] Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR).

[38] International Procurement Instrument (IPI)—regulation on access to the public procurement markets of Member States.

[39] The International Procurement Instrument, introduced in August 2022, gives the EC the right to conduct proceedings and impose penalties in connection with violations by non-EU countries of the rights of EU companies in public procurement procedures. Regulation 2022/1031 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 23 June 2022, www.eur-lex.europa.eu.

[40] Depending on how the situation develops, this may be considered part of a decoupling or derisking policy.

[41] F. Chimits, “Staying united is the best way for the EU to reduce its trade vulnerabilities on China,” MERICS, 19 March 2025, www.merics.org.

.jpg)

.png)

.png)