Putin's Fifth Term: What will be Russia's Domestic and Foreign Policy?

Vladimir Putin’s extension of his rule will reinforce totalitarian tendencies within Russia’s political system and intensify the warlike course of its foreign policy. Russia’s leader will want to undermine Western support for Ukraine and bring the conflict to an end on Russia’s terms. Countries supporting Ukraine may increase the political, economic, and military pressure on Putin’s regime by accelerating arms supplies to Ukraine, enforcing sanctions more effectively, and delegitimising the Russian leader.

Gripas Yuri/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

Gripas Yuri/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

The efficient 15-17 March plebiscite in Russia consolidated Vladimir Putin’s position atop the power elite. The pseudo-presidential election confirmed the high mobilisation of the administration, security services, and pro-government media to maintain the regime. The official, albeit manipulated, election results gave Putin 87% of the vote against a turnout of 74%. Out of the regime’s fear of political competition and possible destabilisation of the voting process in Russia, inconvenient contenders, including Ekaterina Duntsova and Boris Nadezhin, were not allowed in the election. By completely controlling the electoral process, the authorities reinforced the message to the Russian public that there is no alternative to Putin and that public support for the war against Ukraine is only growing.

Implications for Domestic Politics

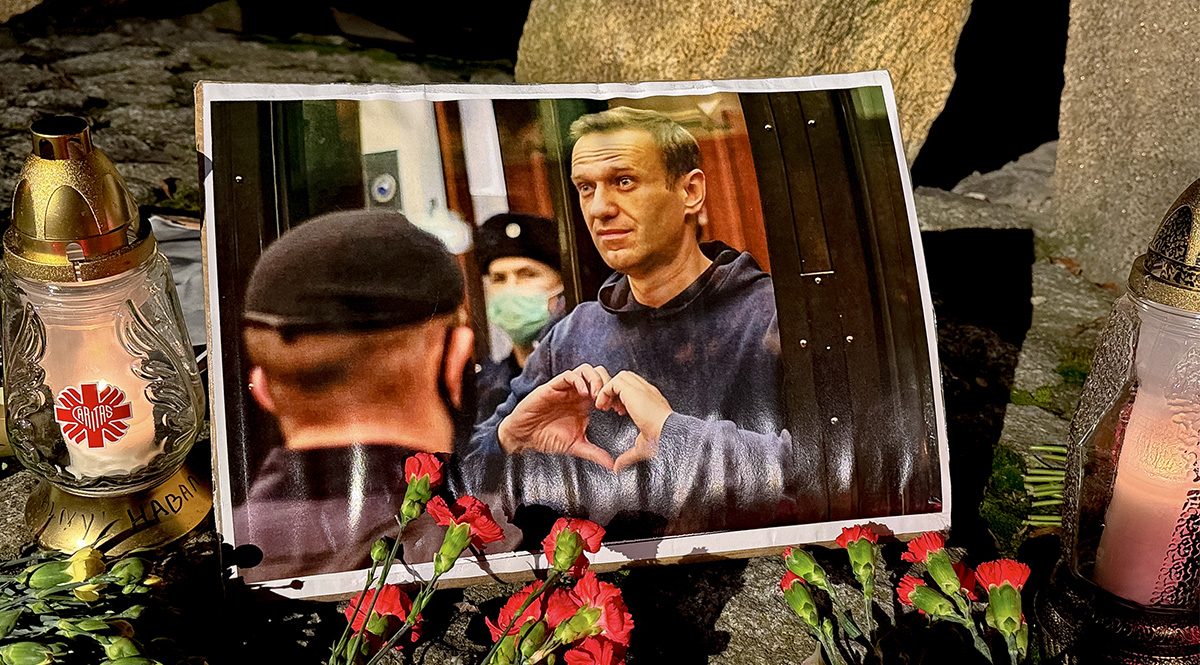

The continuation of Putin’s rule will consolidate a political system based on his personal leadership and the kleptocratic and mafia-style governance of the state. There will be further instrumentalisation of violence and repression as a means of enforcing loyalty. The elimination in an assassination attempt of the recent rebel Yevgeny Prigozhin (23 August last year) was a signal of discipline for the power elite, while the death in a penal colony on 16 February of the opposition activist Alexei Navalny was supposed to be a deterrent for anti-government Russians. In view of the growing repression in Russian society, the number of anti-war expressions is decreasing, while social apathy is increasing. At the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine, the Russian prosecutor’s office prosecuted around a thousand people each month for “discrediting the army”, including the use of pacifist slogans. Today, there are five times fewer such cases.

Putin is using the war in Ukraine to reward loyal collaborators. Oligarchs involved in the war effort receive state contracts for components, equipment, or fuel for the Russian armed forces or arms factories. Forbes magazine’s latest list of the world’s richest people included 125 Russian billionaires—15 more than a year ago. According to an investigation by the website Project, more than half of the richest Russians are war profiteers. They include Gennady Timchenko (Novatek, Sibur), brothers Arkady and Boris Rotenberg (energy and construction companies), Yuri Kovalchuk (Bank Rossiya), Alexei Mordashov (Severstal), and Oleg Deripaska (Rusal).

Putin’s social contract with Russians was renewed in return for the Russian public’s acquiescence to the “long war”. It involves the transfer of money and privileges to fighting soldiers, National Guard troops and their families, support for the poorest, and provision for large families. On 30 March this year, Putin instructed the Russian government to allocate an additional RUB 2.7 trillion ($29.2 million) for social purposes as part of the state’s six-year development plan until 2030. For the promise of achieving state superpower status, Russians are expected to come to terms with a diminished sense of personal security, which includes Russian border regions under Ukrainian fire (i.e., the city of Belgorod), energy infrastructure on Russian territory being destroyed by Ukrainian drones, and the risk of mobilisation to the Ukrainian front.

The focus of attention by Russian services on issues of war with Ukraine and intra-Russian “extremists”, which includes the LGBTQ community, simultaneously increases Russia’s vulnerability to other threats. In 2023, the Federal Security Service (FSB) officially claimed that 90% of attempted terrorist attacks were launched by Ukraine, and only 8% by Islamic extremists (while in 2013, cases of the latter accounted for around 80%). As a result of the Russian authorities’ omissions and trivialisation of warnings from, among others, U.S. intelligence, an ISIS faction carried out a terrorist attack on the Crocus City Hall near Moscow on 22 March this year. Unwilling to acknowledge the failure of the Russian services, Putin linked the attack to Ukraine.

Foreign Policy Implications

Putin will further reinforce Russia’s confrontational course towards the West. With the U.S. and EU in the middle of election campaigns, the Russian government will promote anti-Ukrainian propaganda and sharpen political divisions. The Russian aim includes the blocking of the $61 billion support package for Ukraine in the U.S. Congress and boosting support for extreme parties with anti-Ukrainian views (such as Germany’s AfD) in the European Parliament elections in June this year. Putin also plans to go on the offensive on the Ukrainian front towards major cities, such as Kharkiv, to force concessions from the West on Russian terms. These will include seeking supporters to block Ukrainian membership of NATO and the EU and recognise the country as part of Russia’s sphere of influence.

Implementing the guidelines of its latest foreign policy concept from last March, Russia will strengthen its strategic partnership with China, deepen military cooperation with North Korea and Iran, and undermine the influence of Western countries in Africa and South America. To this end, Russia will support them at the diplomatic level (in March this year, Russia vetoed a UN resolution to extend the mandate of the expert panel on the implementation of sanctions on North Korea), politically (Russia regularly criticises the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or the “Quad”, composed of Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S.) and economically. Russia is becoming dependent on China. For example, Chinese car manufacturers have gained 55% of the Russian market (in 2021, they had 8%), and loans from China to Russia quadrupled in the first year of the war.

It will be important for the Russian government to regain its lost position in the South Caucasus and Central Asian countries, which are key for Russia in, among other things, circumventing Western sanctions. Exports from Armenia to Russia (including dual-use items) have more than quadrupled compared to the pre-invasion period. In contrast, the previous reduction in diplomatic engagement in the region has resulted in an increase in the countries’ contacts with the EU, the U.S., and Turkey. Russia will want to return to its position as the main mediator of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Putin’s term in office will last until 2030, which will result in a further militarisation of socio-political life inside Russia and a strengthening of its aggressive actions outside it. Russian society, exposed to war propaganda and so-called patriotic education, will continue to support the Russian leader. Due to labour market shortages and public concerns about mobilisation, Putin will only officially carry it out if there are decisive setbacks on the Ukrainian front. Instead, the Russian authorities are counting on volunteers to go to the front in Ukraine as part of the spring conscription (from 1 April this year) of 147,000 soldiers. Putin’s system is stable, but it is not sustainable. In the medium term (2-3 years), when possible war funding problems arise and the economic security of the elite weakens, there could be a revolt in the surrounding of the Russian leader.

Faced with the prospect of a Russian offensive in Ukraine and Russia’s increasing hybrid activities against NATO and EU states, the West should continue to signal unity. An opportunity to do so will be at the Alliance’s upcoming summit in Washington in July this year. Unlocking the support package in Congress and increasing arms supplies to Ukraine would act as a pre-emptive measure against Russia’s attempts to impose surrender terms or an unfavourable truce on Ukraine. Western states should furthermore strengthen their own military capabilities and find the political will to delegitimise Putin as Russian president, for example, by declaring him a war criminal with whom diplomatic talks are not to be undertaken. Supporting Ukraine with active defence conducted on Russian territory (by disabling Russian energy infrastructure) is also being considered. The West may also increase pressure on Putin’s corrupt system, including by limiting revenues from the illegal transportation of Russian oil by a shadow fleet and more effective implementation of sanctions.

(1).jpg)