Putin 5.0-Russia's Pseudo-Elections Certify Leader

On 15-17 March, the Russian Federation held its presidential “election”, which was neither free nor democratic. To minimise disruptions of the voting process, the regime kept the nominal contenders for Vladimir Putin to a minimum and encouraged online voting. The showpiece plebiscite was intended to reassure Russians that there was no alternative to the Putin system.

Maxim Shemetov / Reuters / Forum

Maxim Shemetov / Reuters / Forum

How did the voting look?

The first presidential “election” since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine was technically conducted mostly smoothly, albeit in violation of democratic rules, including freedom of choice. Apart from minor incidents and an opposition action calling for Russians to vote on the last day at noon, the Russian electoral system passed the test of loyalty to Putin. Voting was also conducted in Ukrainian territories occupied by Russian troops, another violation of international law by the Russian Federation. The pseudo-election should therefore not be seen as legitimising Putin as Russian president.

What were the official results of the vote?

According to the official election results, Putin received 87.28% of the vote. Nikolai Kharitonov (Communist Party) got 4.31% of the vote, Vladislav Davankov (New People) won 3.85%, and Leonid Slutsky (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia) gained 3.2% of the vote. The results are in line with Putin’s expectations, including the reported high turnout, which nationwide was the highest ever in the history of post-Soviet presidential elections in Russia at 77.22%. To increase participation, illegal voting was conducted in the occupied territories of Ukraine in an early mode (between 25 February and 14 March). Turnout there was reportedly over 80%, with Putin gaining over 90% of the vote. The voting system allowed for greater manipulation, for example by voting online, voting off-site, or at home.

Why did Putin decide to remain in power for another term?

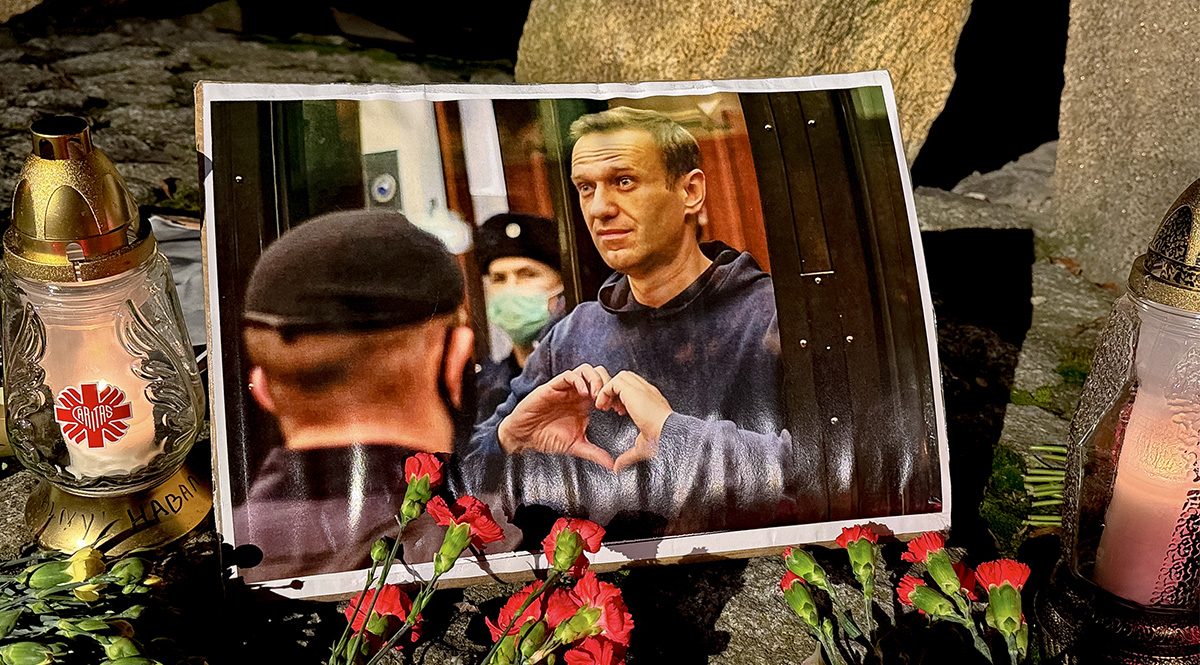

To maintain Russia’s authoritarian system of government, Putin decided on constitutional amendments in 2020 that gave him the right to run for election again and rule until as late as 2036. Putin aims to use his next term to discipline the power elite, especially after Yevgeny Priogozhin’s military mutiny last June. To eliminate any political alternative for voters, only minor, unrecognisable counter-candidates—appointed only by political parties already present in the Duma—were placed on the ballot to give the impression of pluralism. In addition, just before the election on 16 February, Putin critic and opposition figure Alexei Navalny died in unexplained circumstances in a Siberian penal colony. Although Putin declared that he was not taking part in the election campaign, he promised additional social transfers, while propaganda portrayed him as the only guarantor of security and strengthening Russia’s sovereignty.

What impact has the course of the war in Ukraine and the opposition’s actions have on the vote?

The failure of the Ukrainian offensive last year and the difficulties of the Ukrainian army in acquiring weapons were used by the pro-Kremlin media to reinforce Putin’s image as defender of Russia. This image was partly spoiled by the incursions of Russian military groups, including the Russian Svoboda Legion and the Russian Volunteer Corps, into the border regions with Ukraine. They were supported by artillery fire from the Ukrainian side in actions in the town of Belgorod. There were also drone attacks on Russian refineries and the Domodedovo airport near Moscow.

Russia’s leader also had to contend with the real opposition’s action calling for Russians not to vote online but instead to turn up at electoral commissions at noon on Sunday. The “noon against Putin” action gained popularity in Russia’s major cities—Yekaterinburg, Saint Petersburg, Kazan, and Moscow. Even more visible were the queues of Russians voting at this hour abroad, with the largest numbers in Yerevan, Berlin, London, and Istanbul.

What will be the consequences of Putin’s prolonged rule?

The extension of the Putin system will mean ever-increasing militarisation of Russia’s socio-political and economic life. The Russian authorities will intensify repression against anti-regime citizens who, for example, had the courage to submit signatures for Boris Nadezhin’s would-be candidacy (he collected 211,000 in total), attended Navalny’s funeral, or voted at noon on Sunday. Members of the Russian opposition in exile may also be at risk (Navalny’s colleague Leonid Volkov, who lives in Lithuania, was attacked and beaten just before the vote). The ageing power elite—most of the high-ranking Russian officials are around 60 years old—will try to maintain their influence through nepotism, by having descendants govern, such as Boris Kovalchuk, the son of Putin’s “banker”, who was appointed deputy head of the presidential control department in March this year. However, as long as Putin succeeds in stabilising the power system, he will not resign from his post. If the leader is weakened, the hermetic nature of the Putin system may provoke further revolts (i.e., Prigozhin-style demonstrations).

What impact will Putin’s new term have on Russian foreign policy?

Putin will present the official results of the “election” as Russians’ acceptance of the continuation of the war in Ukraine. Putin sees it as one of the stages of confrontation with the West, which will mean an increase in hybrid actions against NATO countries, including Poland. At the same time, Russia will increase its rhetoric on the use of nuclear weapons to try to reduce Western aid to Ukraine. To carry out a new, larger offensive in Ukraine, the Russian leader may decide to launch another wave of mobilisation, although it will be conditioned by developments on the frontline and the U.S. presidential election. Putin is counting on Republican Donald Trump winning, who, by cutting aid to Ukraine or completely, could force it into talks with Russia. To counter this possibility, Western countries may consider not recognising Putin as Russia’s legitimate president.