Progress of the Debate on Sustainable Farming in the EU

In October, the European Parliament approved the goals set by the European Commission (EC) in the Farm to Fork Strategy. This boosted the effort to reduce the negative effects of agriculture on the climate and environment. The details of the strategy must, however, still be negotiated, with the majority of Member States less enthusiastic about the planned reforms than MEPs. Certain sectors of the agri-food industry are striving to slow the transformation. In October, the European Parliament approved the goals set by the European Commission (EC) in the Farm to Fork Strategy. This boosted the effort to reduce the negative effects of agriculture on the climate and environment. The details of the strategy must, however, still be negotiated, with the majority of Member States less enthusiastic about the planned reforms than MEPs. Certain sectors of the agri-food industry are striving to slow the transformation.

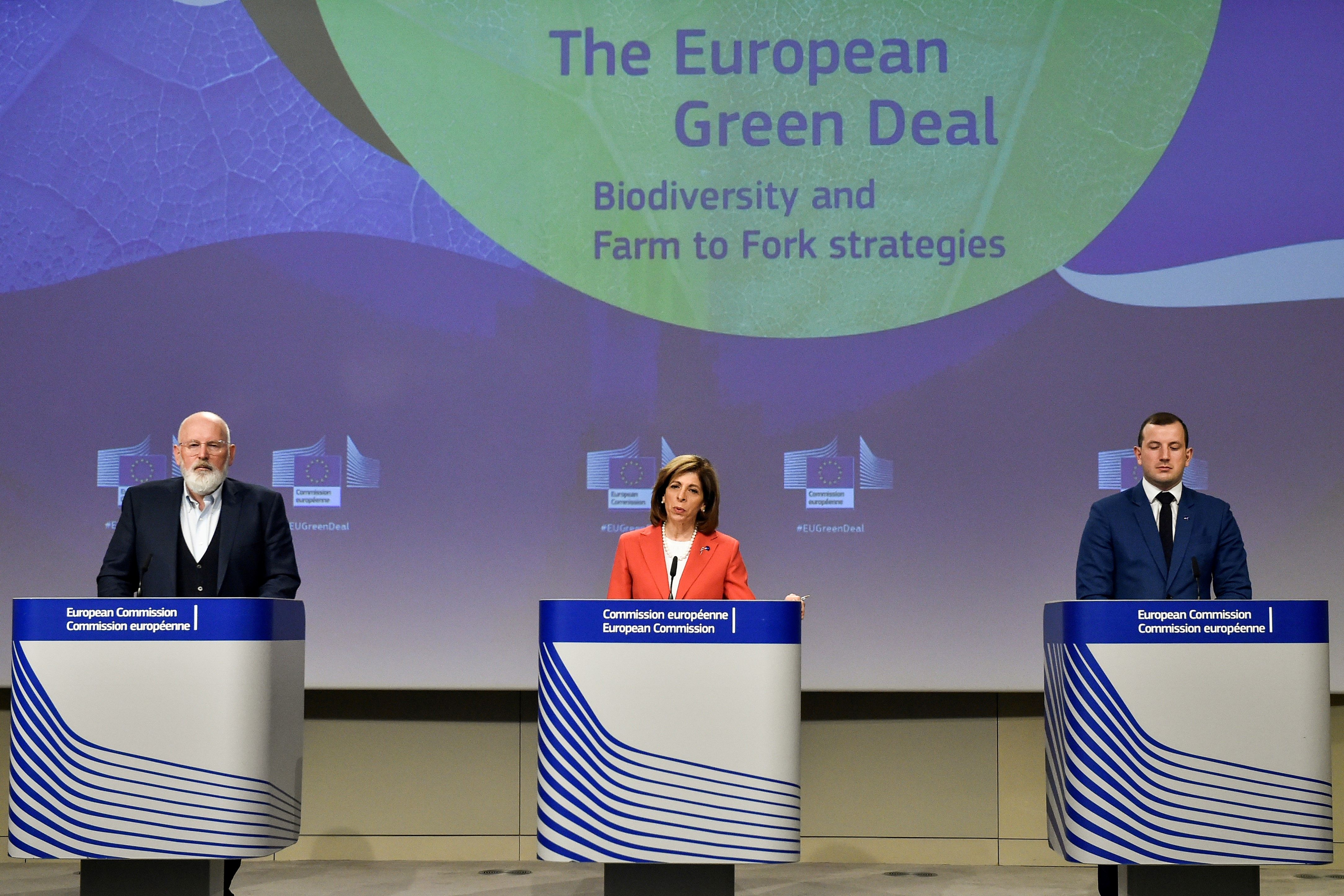

Photo: Xinhua/Zuma Press/Forum

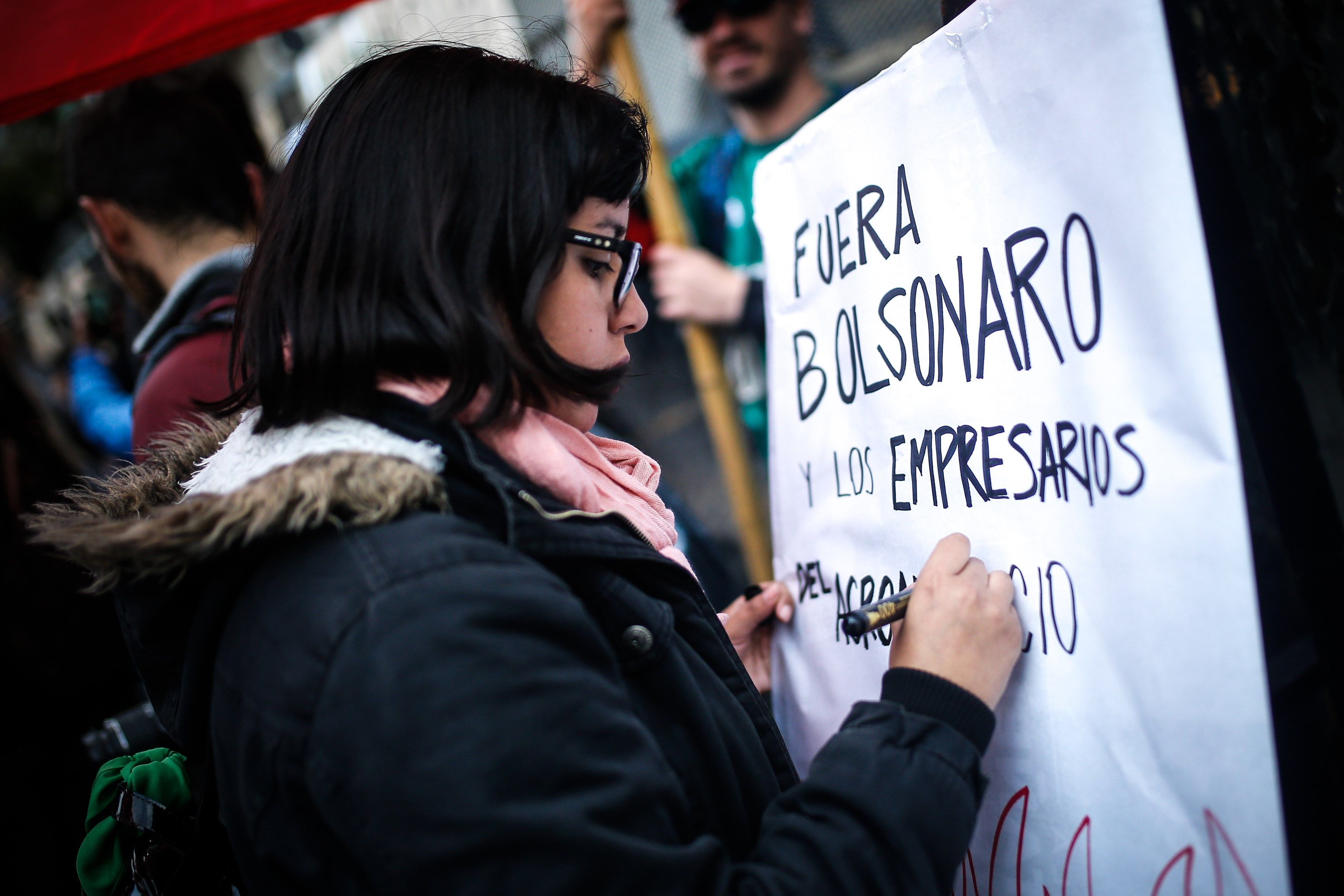

Photo: Xinhua/Zuma Press/Forum

The EC unveiled its Farm to Fork Strategy (F2F) in May 2020. It is part of the EU flagship European Green Deal and aims to make agriculture more sustainable. The EC’s proposals included reducing the use of pesticides and fertilisers and enlarging the area devoted to organic farming. In the coming years, the Commission will publish a number of legislative proposals to translate its ambitions into legally binding commitments.

The Context

Environmentalists, scientists, and some politicians (mostly those hailing from Green parties) have raised their critique of intensive agriculture, which relies on significant amounts of pesticides and fertilisers, leaving a destructive impact on the environment and climate. Some aspects of production, consumption, and the sale of food (particularly mostly unhealthy highly processed food) are also challenged. The EU’s and Member States’ actions designed to reverse the negative trends are often judged ineffective. The European Court of Auditors (ECA), in a report published in June, claimed that considerable funds devoted to climate goals within the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have yielded scant results; for example, emissions of greenhouse gases from agriculture, which account for roughly 10% of total EU emissions, have not decreased since 2010. The ECA stressed that while the majority of emissions come from livestock, the CAP does not promote a reduction either in numbers of animals or meat consumption. Last year, the institution put forward similarly critical assessments of EU actions designed to protect biodiversity, monitor the use of plant protection products, or in promoting a reduction in use.

The majority of Member States are, however, sceptical about adopting more ambitious climate and environmental goals under the CAP and about strengthening conditionality by increasing the portion of payments to farmers dependent on fulfilling concrete obligations. The obvious and main reason behind this attitude is fear of losing funds in case the targets are not met. The ongoing CAP reform is a case in point. According to a preliminary deal struck in June between representatives of the EP and of the Council, the policy will be implemented in a way that is consistent with the F2F goals. Yet, the requirements related to environmental protection and climate were made less stringent in relation to the Commission proposal of 2018.

Dispute about Costs and Benefits

The EC presented F2F without a complex impact assessment. Relevant studies are to be published later with the legislative proposals. Stakeholders critical about the strategy concept have invoked the analysis by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), an advisory body of the EC, which stated that even though implementing F2F could bring about a reduction in emissions, it could also result in less agricultural output and higher prices. Threats to the Union’s food security were emphasised by COPA-COGECA, an influential organisation representing mainly large agricultural producers and backed by other associations, including livestock farmers and producers of fertilisers, pesticides, and animal feed.

The EC claims that the JRC study is not a complex impact assessment, and the analytical model it used omitted a number of important factors, such as changes on the demand side. If the Union manages to reduce food waste and consumption of meat, less production will not be a threat to food security. Meanwhile, more generous financial assistance to farmers embracing sustainable methods will protect them against drops in revenue. NGOs in favour of the strategy emphasised that the analyses that focus on the drawbacks neglect the mounting cost of inaction seen in the increasing frequency of natural disasters, environmental degradation, and reduction in biodiversity.

The EP adopted a resolution in which it approved the F2F goals while emphasising that the Commission should present thorough impact assessments with legislative projects. This position was supported by 65% of MEPs, but votes on individual amendments showed divergence within this majority. Christian Democrats, the largest political group in the chamber, wanted to soften some of the requirements, including the call for a binding target to halve the amount of pesticides used by farmers. After these attempts failed, 40% of Christian Democrats voted against the resolution or abstained. A passage condemning overconsumption of meat also raised controversy. A motion to remove it, initiated by centre-right MEPs, was rejected by only 19 votes in the 705-seat chamber.

International Dimension

A majority in the EP and among Member States believe that the evolution in European agriculture must go hand in hand with the promotion of Community norms beyond its borders and exclusion from the single market of products that do not fulfil them. The EP has called for modifying existing trade agreements and including appropriate clauses in future deals that would oblige trade partners to abide by EU standards. In the resolution, the MEPs stressed that the trade deal with Mercosur was insufficient in this respect and should not be ratified. How to reconcile the drive to develop trade relations with the promotion of sustainable development is an issue that polarises the main political forces. The amendment was supported by just 56% of MEPs, and none of the three largest political groups (Christian and Social Democrats, and the centrist-liberal Renew Europe) managed a united front.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture criticised the Commission’s plans. An analysis from the department warned of a drop in agricultural output in the EU and elsewhere should other states adopt the EU’s approach. However, the American denunciation of the strategy is likely motivated not just by the concern for world food production but also by the fear of barriers to U.S. exports because of tighter EU standards.

Conclusion and Prospects

The EP’s support strengthens the Commission in its drive to implement F2F; however, the Member States’ scepticism of binding environmental targets, as well as the divisions in the EP regarding some of the key points of the strategy, suggest that the extent of the requirements for the states could still be reduced. The proposals strike at the interests of influential and well-organised sectors of industry, which will continue to question the benefits of the strategy and advocate its modification.

The CAP strategic plans to be prepared by every Member State by the end of the year will be an indicator of their determination to reform. They will reveal to what extent states want to use EU funds to support the evolution of agriculture along the lines suggested by F2F.

Changes in consumer behaviour are one of the conditions for the strategy’s success. Progress towards healthier diets—according to data from 2019, over half of EU citizens are overweight—should not only drive up demand for products of organic farming but also lead to a reduction in healthcare spending.

Effective promotion of EU standards in the international arena will facilitate and speed up the implementation of F2F. However, the U.S. and Mercosur members have a different vision of the future of farming and accuse the EU of protectionism. African states, where the model of intensive industrial agriculture is less widespread, could be more open to cooperation.

Products in the agri-food sector constitute 14% of the value of Polish exports, and the trade balance has been consistently positive (it has grown by eighteen times since accession to the EU). This successful record is a disincentive to reforms in agriculture. However, the consequences of climate change and water scarcity are already becoming significant threats to agricultural activity. Poland has been devoting a relatively small part of its CAP funds to environmental and climate goals. Therefore, a key challenge will be to design projects within the framework of a reformed CAP that encourage farmers to embrace activities that will lead to reduced emissions, thrifty use of pesticides, and protection of biodiversity.