European Agriculture: Climate and Other Environmental Challenges

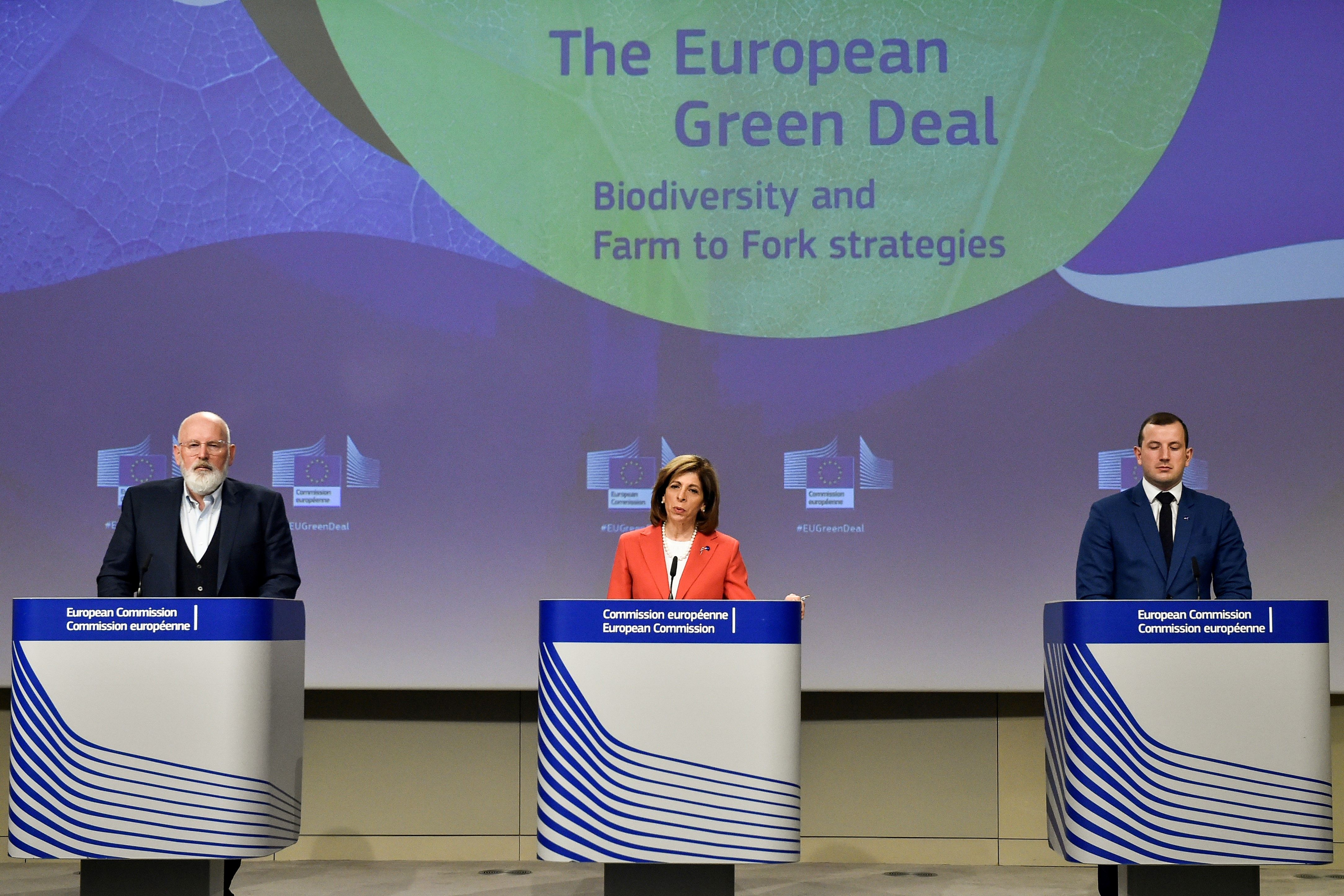

On 20 May, the EC published the “Farm to Fork Strategy” and the “Biodiversity Strategy for 2030”. They are part of its flagship Green Deal this term. The documents spell out a number of objectives concerning production, processing, and consumption of food, and the protection of the environment. If adopted, the strategies will have a significant influence on European agriculture.

Commission Proposals

The starting point for the strategies is a critical assessment of the side effects of current farming and food processing practices, which, the Commission notes, contribute to climate change and environmental degradation. The criticism is focused on intensive farming, particularly monocultures, and the use of large amounts of fertilisers and pesticides, which pollute the environment and harm populations of non-targeted insects and birds. Another culprit, large-scale livestock farming, is responsible for 70% of greenhouse gas emissions generated by agriculture while the wide use of antibiotics in animal breeding is linked to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria dangerous to both animals and humans.

To make agriculture more sustainable, the EC has put forward a number of targets to be achieved by 2030. It proposes to reduce the use of chemical pesticides by 50% and fertilisers by 20%, and halve the sales of antimicrobials. In addition, 10% of current farmland is to be excluded from production (as fallow land, hedges, ponds or non-productive trees) in order to increase carbon sequestration, improve water retention, and provide habitat for animals, birds, and insects. The EC wants to persuade more farmers to turn to organic methods, aiming for 25% of agricultural land (currently about 8%). The targets are EU-wide. The goals set for individual Member States will account for the differences in the character of farming, reforms implemented in recent years, and environmental conditions between the states. The EC also announced that when negotiating trade agreements it will ensure that products imported to the EU are farmed according to high climate and environmental standards. It wants to limit unsustainable practices such as imports of large quantities of animal feed based on soy planted on deforested land.

Apart from farming, the strategies also chart a path for changes in food processing, sales, and consumption. The EC will encourage producers to reduce the number of harmful ingredients and amount of packaging, and to introduce clearer information on labels regarding the nutrition value of products. It will promote consumption of locally grown food in order to reduce the number of products transported across long distances (and corresponding emissions).

In the coming years, the EC will present drafts of new legal acts or suggest amendments to existing ones as it implements both strategies. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)—in reform negotiations since 2018—should also contribute to achieving the goals. The EC wants to persuade the Member States to increase the portion of direct payments that is disbursed to beneficiaries if they comply with criteria related to climate and environmental protection. The Commission states that even though the implementation of the strategies should bring economic benefits in the long term, for it to work there will need to be investments in the initial stages; therefore, it wants to increase the CAP budget for the period 2021-2027 by €24 billion (i.e., by 7%), compared to its own proposal from May 2018. Of that, €15 billion will come from the Next Generation EU programme, financed by bonds.

Reactions

COPA-COGECA, a pan-European association of mostly large-scale farmers has emerged as the most ardent critic of the strategies, describing them as “an attack on European agriculture”. Association representatives stressed that the constraints regarding the use of fertilisers and pesticides, as well as the obligation to assign some farmland to biodiversity-enhancing purposes, could endanger the productivity of European farming. They argued that in the context of the economic turbulence caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, burdening farmers with additional requirements is misguided. Similar suggestions to postpone the adoption of the strategies because of the current economic circumstances were spelled out by the Christian Democrats and Conservatives in the European Parliament.

Even though EU ministers of agriculture expressed general support for making farming more sustainable, their comments featured elements similar to the arguments of farm lobby. They claim that the EC has not provided a sufficient impact assessment of the proposed actions. The ministers were concerned that setting higher ecological standards could translate into lower yields and higher prices, which in turn would lead to an increase in imports and harm the competitiveness of European products on foreign markets. Many emphasised that even a larger CAP budget will be insufficient to reach the ambitious goals (the proposed budget is 5% less than the funds allocated in the 2014-2020 period).

The strategies received a largely positive assessment from the Greens, environmental NGOs, and organic farmers’ associations. Representatives of these groups hope that some of the changes in consumer behaviour that occurred during the height of the pandemic, if made lasting, could be conducive to the Commission’s plans. In a number of countries such as Austria, Belgium, and Greece there were surges in demand for locally grown food, often organic and delivered directly by farmers. Proponents of a quicker agricultural transition also emphasised that the pandemic revealed the weaknesses and limited adaptation capabilities of large, monoculture farms, which suffered the most from the sudden shifts in demand. Left-wing representatives, however, also found some faults in the strategies. The Commission was chided for omitting targets related to greenhouse gas emissions and for proposing what they describe as too-timid measures aimed at reducing the consumption of meat.

Conclusions and Prospects

When the EC unveiled its proposals for CAP reform in 2018, it decided that direct payments should remain a key element of the policy. Its intentions presented in the two strategies show, however, that it wants to reduce the importance of that instrument by increasingly linking the financial support for farmers with concrete actions aimed at making agricultural activity more climate- and environmentally friendly. One of the strengths of the strategies is a multidimensional approach: the EC realises that in order to create more sustainable farming, it needs to promote changes in the behaviour of the food processing industry, retailers, and consumers. By putting forward a larger CAP budget than initially proposed, the EC hopes to soften the scepticism, but the majority of the farming community remains unconvinced. The pandemic has put security, including food security, in the limelight, and consequently strengthened the advocates of the status quo who argue that Europe must remain capable of producing large amounts of cheap food (with climate and environmental consequences a secondary issue). Reservations about the strategies as expressed by the ministers of agriculture and a large number of MEPs show that the pace of the transformation suggested by the EC is widely considered too fast. It is therefore likely that the majority of the targets will be limited.

Active involvement of Commissioner for Agriculture Janusz Wojciechowski, who is a staunch advocate of the strategies, could facilitate their promotion in Poland. To implement them effectively, adequate support measures will be needed, especially for sectors in which a transition to a more sustainable model could be particularly challenging, such as large-scale livestock farming or orchards that use considerable amounts of pesticides. Additional funds within the CAP could be used to support organic farms, whose number has decreased in Poland unlike in the vast majority of the Member States.