More Obstacles to Ratification of the EU-Mercosur Agreement

Conditions

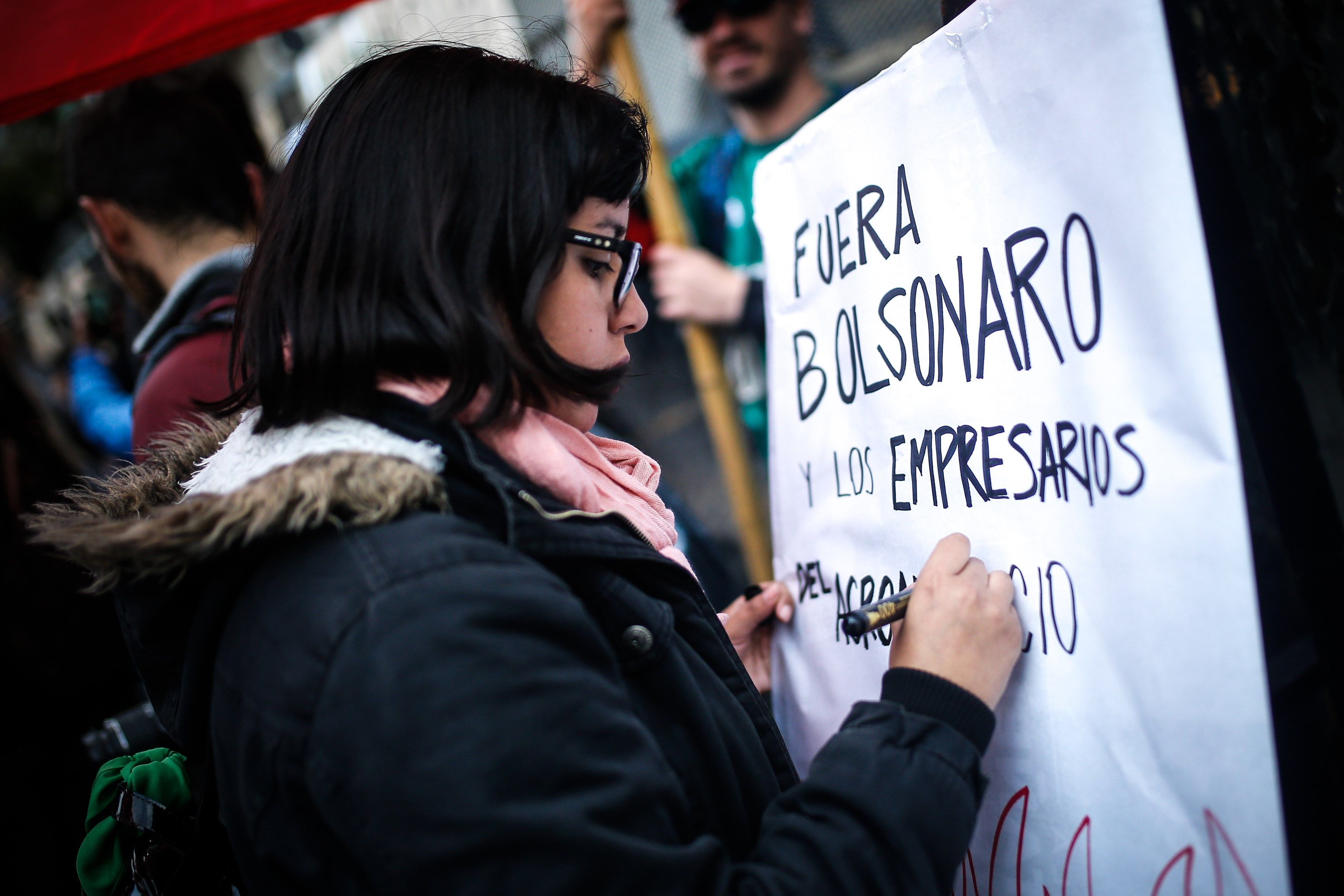

The opposition to ratification of the agreement with Mercosur, which comprises Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, has intensified in the EU since the conclusion of the talks with the bloc. This is mainly in response to the climate policy of the Brazilian government of President Jair Bolsonaro. Data showing an increase in deforestation and fires in the Brazilian part of the Amazon in the past two years, as well as Bolsonaro’s confrontational responses to the EU allegations has amplified criticism of Brazil in the Union. The parliaments of Austria, the Netherlands, Ireland, and the Belgian Walloon region expressed their opposition adoption of the agreement. The Luxembourg and German authorities have expressed scepticism. From the outset, however, the French government has been the main critic because of the importance it attaches to the implementation of the Paris Agreement on climate, among other motives. In October 2020, the European Parliament stated its opposition to the current form of the agreement with Mercosur.

The European Commission has started discussions with Mercosur partners—mainly Brazil—on an additional agreement to enhance commitments on sustainable development (SD). Both the EU and Mercosur reaffirmed their will to reach a compromise, expressed at an informal ministerial EU- Latin American and Caribbean meeting in Berlin on 14 December. The Union’s expectations stem from its ambitions in climate policy. In December 2019, it presented the European Green Deal (EGD), a plan for a sustainable EU economy. In October, the Council of the EU accepted a draft reform of the Common Agricultural Policy in which SD gains importance. Mercosur’s willingness for a compromise with the EU will depend on the former’s consensus on liberalisation within the bloc and on whether they consider the deal with the Union an important means to support economic growth after the pandemic.

The dispute about SD has obscured a broader—more than commercial—meaning of the EU-Mercosur agreement. An important objective is to strengthen EU political partnerships with Latin American countries, including improving conditions to compete, in particular, with such countries as China, which has consistently increased its economic and political influence in the region.

Not Only an Environmental Dispute

The effectiveness of the EU-Mercosur accord’s chapter on SD is the main focus of the current bi-regional discussion. The document’s critics see Brazil’s policy as proof that these provisions will not ensure that the parties to the agreement respect international obligations, including on the protection of forests and the people living there. In September 2020, the French government published a report prepared by external experts. They argued that the environmental mechanisms negotiated by the EU with Mercosur were not effective. They also suggested that the growing trade between the two blocs would increase deforestation of the Amazon—an argument also raised by environmental organisations. In addition, the authors of the study concluded that competitive Mercosur food products would hit EU producers. Agri-food organisations add allegations of lower production standards in the bloc’s countries, for example, the use of pesticides banned in the Union. The EU is therefore seeking additional Mercosur guarantees on SD and trying to meet the demands of Union organisations critical of the agreement.

The Bolsonaro administration has consistently rejected the EU objections and reiterated that the agreement sufficiently safeguards the SD sphere. It stresses that Brazil already meets strict EU requirements. It also argues Brazil adequately protects the Amazon—an argument questioned, for example, by the Brazilian opposition—but it also defends its right to greater economic use of the forest. At the Mercosur Summit in Brazil in December 2019, the presidents of four member states issued a declaration on SD. They stressed that, as developing countries, they need more financial and technological assistance from developed countries to achieve these objectives. In Mercosur, the EU’s negative attitude towards the agreement is also understood as a result of influence from the strong EU agri-food lobby, which fears competition and utilises environmental arguments to block the deal.

The Situation in Mercosur

A convergence of positions among Mercosur members facilitated the conclusion of the talks with the EU. The bloc also finalised negotiations with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA, in August 2019) and intensified trade negotiations with Canada, South Korea, and Singapore, among others. However, in December 2019, the centre-left government of President Alberto Fernández took over in Argentina, which has been pounded by the debt crisis. The new administration enhanced market protections and control of the movement of capital. In April last year, it decided to withdraw from the bloc’s trade negotiations (this did not directly concern the commitments with the EU and EFTA). The deteriorating situation caused by the pandemic and pressure from the other Mercosur states to quickly finalise the trade talks with other partners influenced that decision. In mid-December 2020, Argentina took over the six-month pro tempore presidency of Mercosur and declared it would continue the bloc’s trade negotiations agenda. With the EU, it intends to resolve the remaining technical issues of the deal, but this does not mean readiness to quickly ratify the agreement. The other Mercosur countries, Brazil in particular, support swift adoption of the deal with the EU

Mercosur countries have been hit hard by COVID-19. The IMF’s October 2020 forecast stated that the Argentine economy would contract the most in 2020 (by 12%), although the country has suffered a recession essentially since 2012, except 2013 and 2015. Brazil’s GDP may fall by 6%, which would end its slow recovery after the 2015-2016 recession. Paraguay and Uruguay GDP could fall both by around 5%. The IMF expects a recovery in the Mercosur economies over the coming two years, but these countries will face long-term negative social impacts on rates of poverty and income inequality.

More support from international financial institutions and the attraction of foreign capital will be needed for Mercosur to overcome the adverse effects of the pandemic, and the deal with the EU could support these efforts. Mercosur’s total trade is still characterised by a low share of intra-regional goods merchandise. In 2015-2019, that portion has not exceeded 15% and in 2019 it decreased to around 13%, per UN Comtrade data. In the same period, the EU’s share in Mercosur trade slipped from nearly 17% to 15% and China’s increased from 17% to almost 22%. The development of relations with the latter country is given priority, for example, by the current Argentine government, which wants to engage in the Belt and Road Initiative, and by Uruguay, whose authorities aim to seize all opportunities to increase trade, not only within Mercosur. The EU is therefore not necessarily seen in the region as a first-choice partner.

Conclusions

The ratification of the EU-Mercosur agreement will not happen without a compromise on the SD, but the South American bloc’s members will expect support from the EU in return, such as financial assistance in achieving its objectives in the concerned area. It is unlikely, however, that agreement on an additional SD-enforcement mechanism will remove the objections of environmental organisations or weaken the EU’s agri-food lobby’s accusation regarding Mercosur production standards. Consequently, the EU will need to ensure stronger guarantees on SD in its future trade agreements. The delay in ratification of the deal with Mercosur will urge its members to strengthen cooperation with other partners, mainly China. Paradoxically, developing these links may result in faster deforestation, which the EU will not be able to prevent.

Mercosur’s share in Poland’s trade remains marginal. However, the agreement could create conditions for increased merchandise turnover, including in exports by Polish industrial companies, for example, in the automotive sector, that are part of international supply chains of companies based in other EU countries, Germany in particular. The delay in ratification of the agreement gives the Polish agri-food industry more time to prepare for competition with Mercosur products on the EU market.