Problems Increasing in EU-China Relations

The EU considers the Chinese political support for the Russian aggression against Ukraine as the main obstacle to the development of cooperation with China. At the EU-China summit on 1 April, the EU warned of sanctions on China if it helped Russia wage war. However, the EU is focused more on implementing mechanisms to protect the common market against economic threats from China. The Chinese authorities are trying to normalise relations with the EU to limit its cooperation with the U.S. in the rivalry with China. To this end, the Chinese also aim to take advantage of the differences between EU members’ stances with regard to relations with China and the U.S.

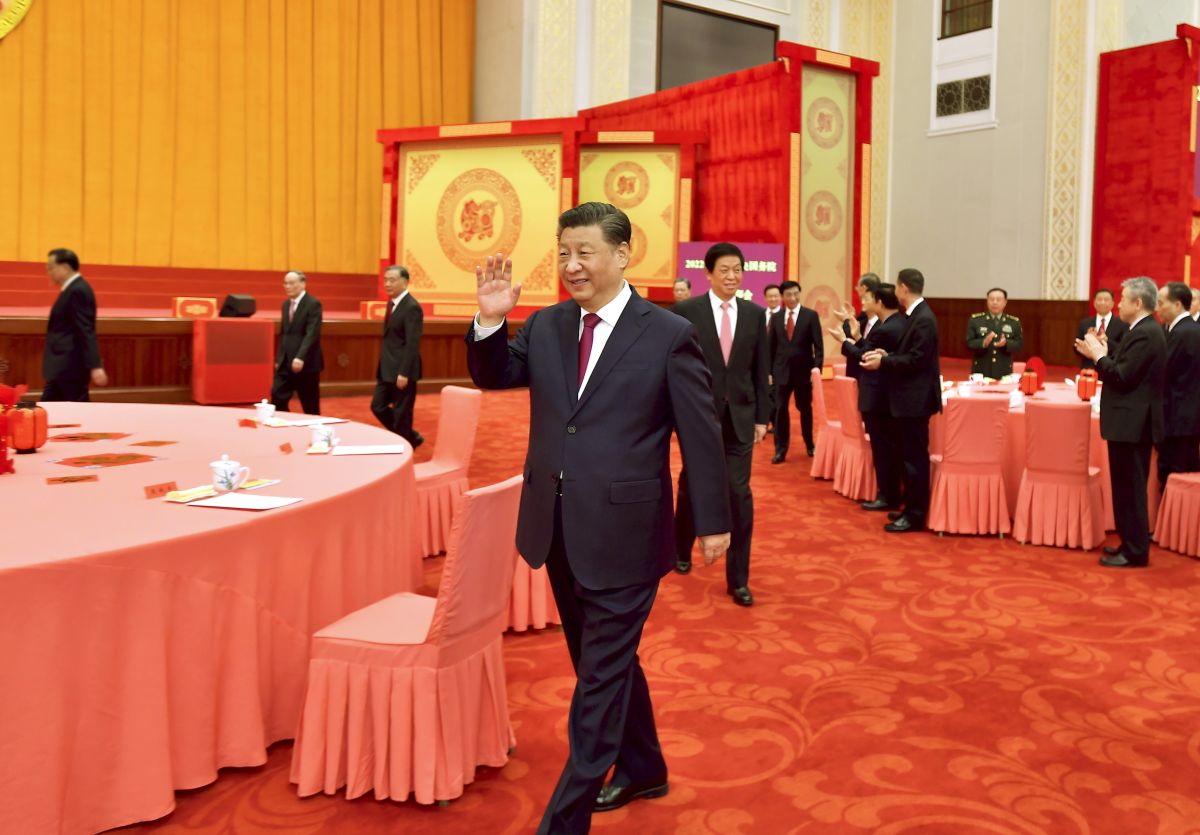

TINGSHU WANG/Reuters/Forum

TINGSHU WANG/Reuters/Forum

The April virtual EU-China meeting confirmed the difficulties in relations between them. The European Union informed China that material support for the Russian aggression against Ukraine or assistance in circumventing the restrictions on Russia will be met with a reaction from the EU, including potential sanctions. The Union also urged China to lift the selective sanctions on Members of European Parliament and economic restrictions against Lithuania. EU representatives raised the issue of human rights violations in China.

For China, the summit was another opportunity to call on the EU to pursue a policy independent of the U.S. and to strengthen political and economic cooperation with China despite the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Provisional arrangements were made for future dialogue sessions on economic matters, the digital field, and human rights. The first one, set for the end of June, is still tentative as the Chinese side has not yet responded to the proposed dates from the EU.

EU Position

Union policy towards China is focused on preventing threats similar to the actions against Lithuania. The legislative process of adopting new instruments aimed at increasing the EU’s capacity for action in trade disputes, but also, for example, in confronting human rights violations, has accelerated. The most advanced work is on the Anti-Coercion Mechanism (ACI), which is to enter into force in mid-2023. It will enable EU members and companies to report situations in which they feel pressure from third countries. If these accusations are confirmed, the European Commission will be able to respond, for example, by blocking imports from these countries. A regulation on foreign subsidies is also being prepared (in May, the EC’s proposal on this issue was supported by the Council and the European Parliament), as well as a ban on the import of products of forced labour to the EU (the EC’s draft is to appear by mid-September). Public procurement procedures have also been modified to allow the issuing agencies to block Chinese entities from participating in them. These instruments will complement existing ones, such as the 2019 investment-screening mechanism.

In the EU’s opinion, suggesting possible sanctions is a sufficient response to China’s political support for the Russian aggression in Ukraine. In the EC’s view, China has no means or instruments to realistically compensate for Russian losses in the financial or energy sectors as a result of the sanctions. Therefore, the work on the catalogue of possible restrictions on China, initiated by the French presidency of the EU Council after the summit, is being carried out slowly. In addition, the EU’s attitude towards China is influenced by the difficult situation of European companies on the Chinese market, resulting from the China’s “zero COVID” policy, which has stopped production in affected areas and led to an outflow of foreign workers from China. Possible restrictions resulting from China’s support for Russia will not improve the conditions for these companies. The pandemic restrictions have made more EU companies re-consider their operations in China. According to a study by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, 23% of 372 analysed entities are considering withdrawing from that market. Similar conclusions were found in an April poll by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Dissatisfaction with the effects of the “zero COVID” policy and the EU-wide reaction to China’s support for Russia have strengthened the cooperation between the EU and the U.S. in regard to China. In April, there were consultations between the EC and U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, and in May the second Trade and Technology Council (TTC) meeting was held on supply chain disruptions, food safety, and other significant matters. Under the TTC, both the EU and the U.S. want to counteract Chinese dumping, for example, in the solar panel sector, and human rights violations, particularly in Xinjiang, including by restricting the import of suspected forced labour products. A working group was also established to assess the reliability and security of suppliers of 5G equipment.

China’s Policy

China is trying to reconcile two goals in its EU policy: on the one hand, it wants to maintain both cooperation with Russia and the rivalry with the U.S., but, on the other hand, it seeks to develop relations with the EU as an important economic partner. Hence, the vague incentives of Chinese authorities to open their market more widely to EU companies, including in investment, or support for the concept of EU strategic autonomy, understood in China mainly as undermining transatlantic cooperation.

The Chinese authorities, even before the Russian aggression on Ukraine, have been trying to take advantage of the differences in the policies of the EU members. They hope that despite the EU states’ current relative unity, sooner or later the divisions will return to the fore, which China then will seek to deepen. This is especially true of Germany, which in May this year was asked directly to support Xi Jinping’s global security initiative. Conciliatory rhetoric also appeared in a Chinese statement following Xi’s talks with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and French President Emmanuel Macron in May.

China’s attempts to deepen relations with Greece correspond to the aim of winning it over. During an April visit by Ambassador Ma Keqing, an envoy of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, she emphasised the importance of Sino-Greek cooperation by referring to this year’s 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries, among other connections. China is also trying to explore the possibility of strengthening relations with the Central European countries (namely Poland, Czechia, Latvia, and Slovakia) that, after the Chinese expressed support for Russia after its invasion of Ukraine, showed growing scepticism about the development of relations with China. In April and May this year, a special representative of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Huo Yuzhen, visited eight countries in the region, including Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Croatia, and Hungary, in an attempt to present a conciliatory approach and suggest Chinese disagreement with Russia’s war, without giving up, however, anti-NATO and anti-American rhetoric. The official reception to the delegation varied, with some countries holding a conversation at the deputy minister level, but in Poland, for example, Huo Yuzhen was not hosted even at the working level. Offering a similar message in May, Wu Hongbo, a special representative of the Chinese government for European affairs and a former ambassador to Germany, paid a visit to Brussels, as well as Czechia and Romania.

Another expression of China’s conciliatory attitude towards the EU was the ratification by China in April of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Conventions on Forced Labour. In 2020, in the negotiated text of the EU-China Comprehensive Investment Agreement, China pledged to “make efforts” to ratify the most important ILO conventions.

Conclusions

The dominant belief in the EU institutions is that it is not necessary to transform the political declarations made during and since the April summit into a specific catalogue of possible restrictions on China. Considering the EU’s clear problems in adopting tougher sanctions against Russia and the Union’s much greater ties than Russia to the Chinese economy, the consent of all Member States to impose sanctions on China is unlikely. The EU instead will continue to focus on launching new economic anti-coercion instruments, including the ACI, and, in cooperation with the U.S., to criticise Sino-Russian cooperation and threaten consequences in order to prevent China from actions seeking to change the international order in cooperation with Russia. This approach will be supported by the Czech presidency of the EU Council starting in July. The Czech authorities are generally sceptical about China, and during the Council presidency they plan to devote a lot of attention to the EU’s actions towards the Indo-Pacific, including trade relations with Australia, Indonesia, and New Zealand.

The signals from China about the will to develop closer relations with the EU are mainly rhetorical and therefore ineffective. Chinese accusations that NATO provoked the war in Ukraine and repeating Russian propaganda, including calling into question Russian war crimes, limit the scope of further cooperation with the EU. For internal reasons, China is not ready to change its policy towards Russia to take into account the demands of the EU. It also underestimates the importance of the change in EU policy since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the wide recognition of China as Russia’s global partner. This misappraisal of EU interests and policy, as well as the focus on the autumn 20th CCP Congress, reduce the likelihood of a breakthrough in EU-Chinese relations in the coming months.