Changes in China's Policy Towards Countries of Central Europe

In 2021, China modified its policy towards the countries of Central Europe, differentiating between them in terms of their relations with Taiwan, the U.S., or influence on EU policy towards China. Some states viewed as friendly, including Hungary, Serbia, and Poland, are encouraged to cooperate through such means as investments, but against perceived opponents, such as Lithuania, Czechia, and Slovakia, China uses political and economic sanctions. Relations with the countries of the region are increasingly treated by China as an instrument of influence vis-à-vis Germany and institutions of the EU. It is in the interests of Central European countries to support the reduction of the EU’s economic dependence on China and to restrain political cooperation with it.

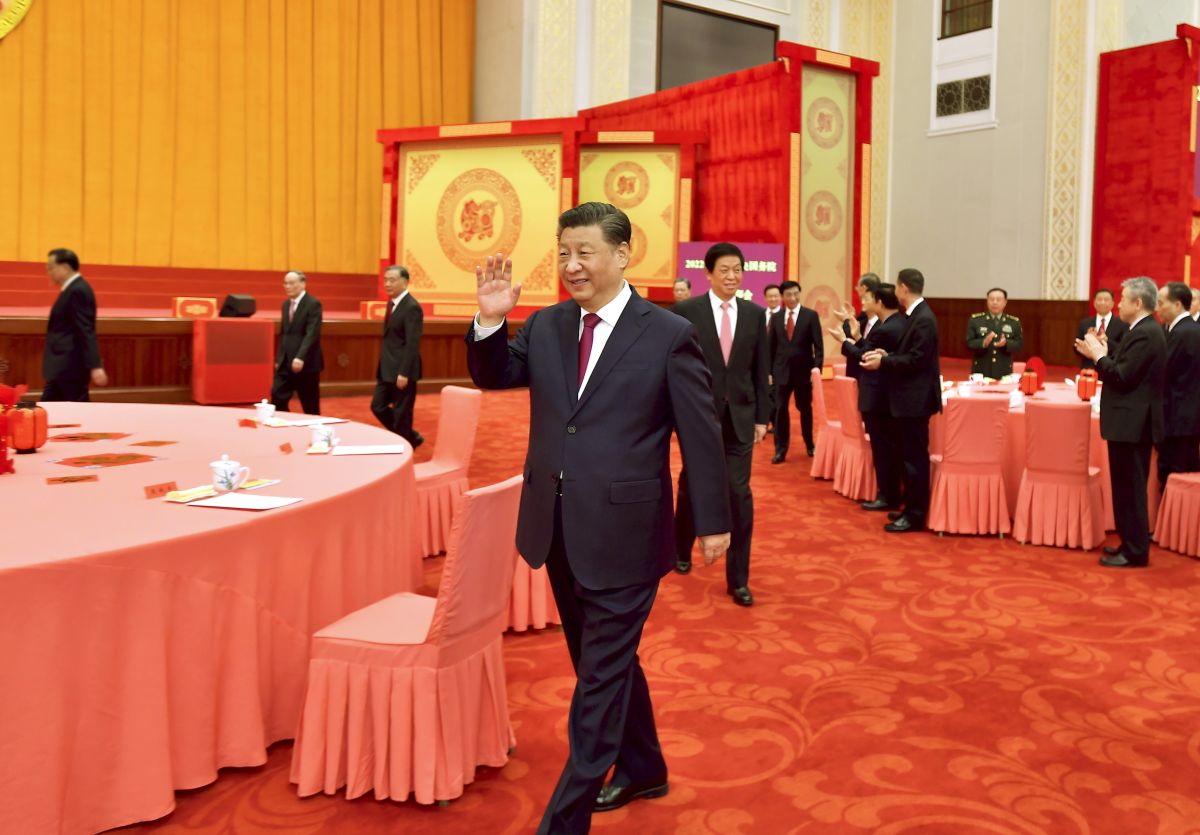

Li Tao/Xinhua News Agency/Forum

Li Tao/Xinhua News Agency/Forum

The correction in China’s policy towards Central Europe results mainly from a broader change of its regional countries policy in the last year. This was especially true of Lithuania, which, by seeking to intensify relations with the U.S., strengthened relations with Taiwan and cancelled its participation in the “17+1” (now “16+1”). Disagreement with China’s policies towards the EU, including the use of disinformation and violations of human rights, for example, in Xinjiang, was also signalled by Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. China’s approach was also influenced by a perception of a negative reaction to U.S. policy by some regional countries (including Poland and Romania) regarding, for example, the suspension of sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 (NS2) gas pipeline.

Partners

China considers as partners countries that are interested in economic cooperation and do not criticise its internal policies or violations of human rights. These states often declare their will to intensify contacts with China as part of a multi-vector foreign policy. Such states include Croatia, Hungary, North Macedonia, and Serbia. For China, these states are the main target for future “16+1” initiatives, particularly infrastructure. In return, China expects international support for its demands, including opposition to U.S. or EU sanctions on China, as well as against instruments oriented to protect the Union’s market, such as the anti-coercion instrument (ACI) being developed. China also wants these countries to globally recognise the success of its development model.

China’s approach to Poland is special in nature. China has noticed the political differences of the Polish authorities in relations with the U.S. and the disputes with EU institutions. China is aware that Poland considers the alliance with the United States to be of key importance for its security, especially the threat from Russia. However, the participation of the President Andrzej Duda at the “17+1” summit in February 2021, followed by the visit of Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau to China in May last year were recognised by the Chinese authorities as signals of Poland’s readiness to strengthen contacts. Therefore, the Chinese decided to intensify the political dialogue with Poland. In November 2021, Huo Yuzhen, a special representative of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for relations with Central and Eastern Europe, paid a visit to Poland. In December, virtual meetings of the Poland-China Intergovernmental Committee were held, with discussions on cooperation in logistics and transport (a meeting between foreign ministers is planned for this year). The culmination of this process was the official visit of the Polish president to China in February this year. During his stay, President Duda also took part in the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Beijing. Even before his arrival, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs described the visit as a sign of the international community's readiness to build a “common future for mankind” with China. This phrase refers to the new concept by Xi Jinping that in practicality means the creation of global spheres of influence, among other things. In a statement issued after the Xi-Duda meeting, the Chinese side emphasised the importance of economic cooperation (including logistics or Polish food exports to China), as well as the will to cooperate within the framework of the revised “16+1”. However, the communiqué did not mention security issues in Central Europe, which were pointed out by the Polish side as part of the official talks.

Opponents

China has also identified opponents, which means countries that, among other things, criticise the lack of observance of human rights in China, seek to strengthen contacts with Taiwan, and/or support the tightening of EU policy towards China. This group includes Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Romania. Most of them (e.g., the Baltic states) perceive relations with China through the prism of an immediate threat to their security due to Sino-Russian cooperation, which was strengthened in February by a joint statement following the Xi-Putin meeting in Beijing. At the same time, they assess and publicly emphasise that Chinese policy, such as economic sanctions targeting Lithuania, negatively affects EU cohesion.

Depending on the actions of a given country, China’s reaction includes criticism by its foreign ministry or restrictions of bilateral political contacts. China also emphasises the differences of opinion on policy towards China within a given country (including Lithuania) to try to limit its effectiveness on the wider stage. For example, Chinese media reports on meetings between Chinese diplomats and opposition politicians from the Central European country. Economic sanctions are applied in the most sensitive areas, such as Taiwan. The case of Lithuania is telling. After it allowed the establishment of a “Taiwanese” (and not the Chinese preferred “Taipei”) representative office in Vilnius, China stopped importing certain goods from Lithuania, including beef and dairy products. These Chinese informal sanctions against both Lithuanian and foreign companies that use Lithuanian products and components and are present on the Chinese market in the form of investments or sales are new in nature. The Chinese authorities have announced that such entities will not be able to operate in China unless they terminate cooperation with their Lithuanian partners. In this way, China is hitting companies from, among others, Germany and France, putting pressure on these countries to try to force Lithuania to change its policy. This approach reduces the investment attractiveness of Lithuania and disrupts the functioning of the EU’s single market. The effect of this is visible: the Slovenian prime minister had suggested possible consent to the opening of a “Taiwanese” representation similar to Lithuania, but withdrew from it under pressure from the opposition and information from Slovenian companies about the difficulties they were encountering on the Chinese market.

Conclusions and Perspectives

It is key for China in Central Europe to increase economic and political ties with individual countries of the region. However, the offer of cooperation applies only to those countries that will not criticise it, including for violations of international law in Hong Kong or human rights in Xinjiang. Therefore, instead of economic incentives, these countries will mainly be subject to sanctions. For propaganda purposes, the Chinese authorities emphasise the importance of multilateral cooperation with the countries of the region, especially in view of the 10th anniversary of the “16+1” format this year. In reality, however, this initiative carries little weight, and China’s contacts with the region will remain focused on the bilateral dimension.

The rivalry with the U.S. means the region remains important for China, but it leaves the main role in this regard to Russia and gauges the U.S. response to the Russian actions in the region, for example, on Ukraine. China treats the development of relations with Central European countries (cooperation with partners and sanctions against opponents) primarily as additional instruments of pressure on Germany (the most important economic partner in the EU, both for China and Central European countries), as well as EU institutions. In the event of disputes, for example, concerning Taiwan, China may block access to its market for companies from EU countries that pursue policies against its interests.

The actions of China in Central Europe, and especially towards Lithuania, are further proof of the risk of EU economic dependence on China. It makes the Union vulnerable to Chinese influence and thus threatens transatlantic cooperation. Lithuania’s possible submission to the pressure from China, as well as signals from Germany, France, or Central European countries about the inevitability of developing cooperation with China, reduce the effectiveness of the EU. In this context, for example, the consensus needed to launch the ACI or other instruments to protect the single market becomes uncertain.

It is in the interest of the EU to treat China’s restrictions on individual countries as an attack on the entire EU market. Filing a complaint to the WTO on China’s actions towards Lithuania and cooperation with foreign partners with similar disputes with China—the U.S., Australia, Canada, the UK, Japan, and Taiwan have expressed their will to join the WTO case—are not sufficient. EU support for companies forced by Chinese sanctions to change their supply chains and the Union’s introduction of postponed restrictions on access to the EU market for companies using forced labour from Xinjiang, are also very important.