Moldova's and separatist Transnistria's Caution in the Face of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Moldova supports Ukraine and unofficially respects the Western sanctions against Russia. Provocations in April and May 2022 in the separatist Transnistria, declared in 1990 in eastern Moldova as a de facto Russian protectorate, have increased fears of an attack from that territory on the Odesa Oblast of Ukraine or Moldovan areas controlled by the constitutional authorities in Chişinău. This scenario remains unlikely before a Russian siege of Odesa. Poland and its allies from the EU may discourage Russia from intervening in Moldova by supporting the latter’s self-defence capabilities.

Jakub Pieńkowski

Jakub Pieńkowski

Russia is deliberately raising tensions in the Odesa Oblast and Moldova by suggesting that these areas will be the next target of the Russian offensive. The threat stems from a map publicly exposed in March 2022 by Belarusian authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenka that supposedly displayed Russian military plans. The threats were also repeated by the Russian military, activists of the United Russia party, and state media. The justification for intervention is the alleged persecution of Russian citizens and Russophones in Moldova, including a prohibition on display of Saint George’s ribbons, nominally symbolising the Soviet victory in Europe on 9 May 1945.

Moldovan Support for Ukraine

Moldova is pursuing a policy of benevolent neutrality towards Ukraine in its fight against Russia. President Maia Sandu and Prime Minister Natalia Gavriliţa of the pro-presidential Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) condemned the Russian aggression and offered help to refugees. Moldova still hosts around 100,000 of them and has allowed 420,000 people to cross the border so far. It has provided its neighbour about €1.2 million in humanitarian aid. The Moldovan public is almost equally divided between the two sides of the war. According to a WatchDog/IPIS survey from May 2022, 41% of respondents consider Russia’s actions to be “unjustified aggression”, 23% see it as “defending the Donbas republics”, and 16% view it as the “denazification of Ukraine”.

Moldova does not supply Ukraine with arms, even though it could. It refuses to sell the six MiG-29s withdrawn from service in 2009 and unsuccessfully auctioned several times. However, Moldova has offered sappers to help with mine and munitions clearance when a ceasefire comes.

Informal Actions on Russia

Moldova unofficially respects the Western sanctions against Russia. It has distanced itself from Russian suggestions to help it circumvent the SWIFT bank transactions blockade or to help it exchange euros and roubles for Western companies paying for Russian gas. Under the guise of irregularities, Moldova cancelled a tender for the renovation of a heating and energy plant in Chişinău awarded to a Russian company. It also has closed its airspace except for, citing security issues, in the direction of Romania, which has banned Russian airplanes in its airspace.

The informal nature of its actions stems from the Moldova government’s fear of retaliation, specifically the possibility that Russia will cut off gas supplies. Moldova is 100% dependent on this source and is not able to buy gas on the market at current prices. This policy was probably agreed with Western partners, as it was not criticised by any of the many leaders Sandu and Gavriliţa met with.

The Transnistrian Issue. Neither the ruling elite nor the inhabitants of Transnistria want to be involved in the war. In April and May 2022 there were numerous provocations, for example, the ministry of security and barracks were fired on, Russian radio station masts were blown up, and there was a series of false bomb alarms. However, Transnistrian leader Vadim Krasnoselsky, wanting to remain loyal to Russia and not to accuse Ukraine at the same time, only signalled that “the traces of the perpetrators lead to Ukraine” and asked the Ukrainian services for help in the investigation. From the beginning of the war, Krasnoselsky assured both Ukraine and Moldova that there would be no attack from Transnistria. This stems from concerns for the political and business interests of the holding company Sheriff (Шериф), which has real control over the self-proclaimed republic and its foreign trade. The inhabitants of Transnistria are susceptible to propaganda promoting the so-called Russian World (Russkiy mir), but local historical policy has also perpetuated in them a fear of conflict and the memory of Ukrainian aid during the war with Moldova in 1992.

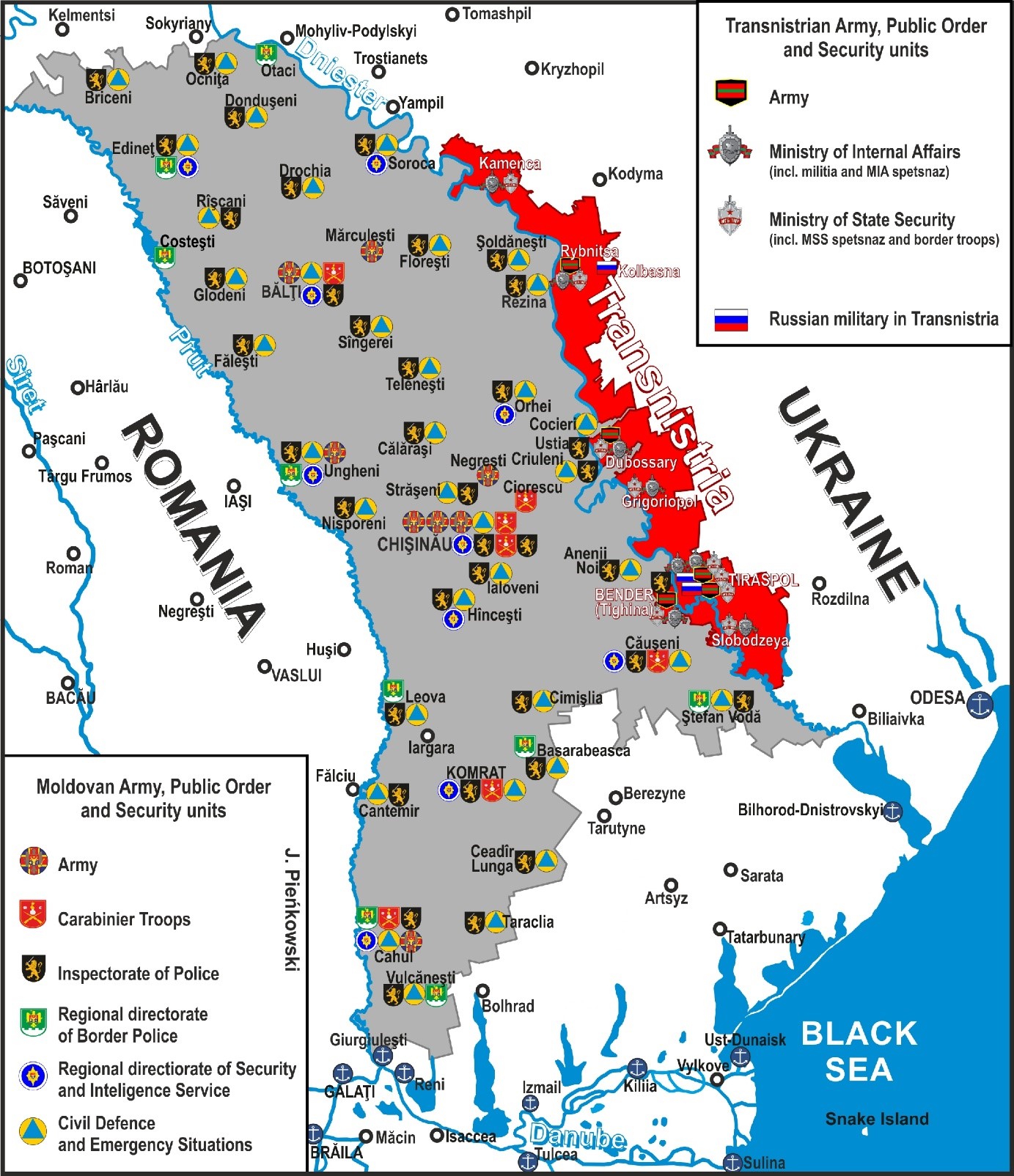

The forces located in Transnistria are not able to threaten Ukraine on their own. They have no aviation, no heavy artillery, and only a dozen tanks. The local army, forces of the Transnistrian Ministry of the Interior, and the Ministry of State Security combined have only about 5-7,000 troops, and in case of a serious crisis Russia will take command of them. The Russian Army has about 2,000 soldiers on the territory. Due to a Ukrainian blockade of military transports to Transnistria, in place since 2014, these troops have a shortage of equipment and are mostly made up of local recruits with Russian citizenship. The only airport in Transnistria is closed and requires repair. Ukraine announced that it will shoot down any Russian airplanes heading there.

Ukraine is ready for a diversion from Transnistria, so it closed the border with the territory, destroyed a bridge on the railway from Odesa to Tiraspol, and blocked roads. At the same time, it excludes a preventive attack aimed at destroying the local and Russian forces there and releasing its own troops guarding the 454 km-long border. Moldova in that case would have to consider Ukraine’s actions to be a violation of its territorial integrity, which results from the Moldovan government’s ambiguous attitude towards the Tiraspol regime and Russian troops in which they simultaneously consider their presence illegal and demand their withdrawal, but also avoid recognising them as occupying forces. Therefore, the advisor to the president of Ukraine, Oleksiy Arestovych, assessed that intervention in Transnistria would be possible only after a direct request from the Moldovan authorities, which exclude it.

Moldova’s Illusion of Security. Moldova emphasises that it is protected against aggression by its policy of neutrality, included in the constitution after the defeat in the 1992 war. This status, however, is not internationally recognised, and Russia is undermining it by keeping troops in Transnistria. Despite this, Sandu and the PAS also refuse to apply for NATO membership in the face of the war in Ukraine. However, in response to Russian threats, Gavriliţa warned that aggression against Moldova would entangle more countries in the war. She also pointed to Romania, which is a member of both NATO and the EU, as the country of citizenship for about 40% of Moldova citizens. She did not refer to an announcement by Vasile Dîncu, defence minister of Romania, that this country would not come to Moldova’s aid without a collective NATO decision.

Successive Moldovan authorities have used neutrality to justify neglect of defence matters. Although the speaker of the parliament, Igor Grosu, and Defence Minister Anatolie Nosatîi declared armed resistance in the event of Russian aggression, Sandu pointed to the country’s inability to defend itself and announced modernisation of the army, without giving any specifics. Moldova’s armed forces have fewer than 4,000 soldiers along with 1,000 militia (carabinieri) subordinate to the Ministry of Internal Affairs in peacetime. The service is not attractive in terms of wages or socially prestigious. They do not have tanks, combat aviation, or effective anti-aircraft and anti-tank weapons. The only newer equipment is used HMMWV vehicles and helmets and body armour for one battalion, which the U.S. donated a few years ago. Although the defence budget for 2022 has increased by 56%, it is only $47 million. That is why Moldova accepted in May a proposal by the President of the European Council Charles Michel for the EU to donate non-lethal military equipment to the country.

Conclusions. Moldova has unequivocally sided with Ukraine and supports it to the best of its limited capabilities. At the same time, it avoids actions and declarations that Russia could use as a pretext for retaliation, such as cutting off gas supplies. A Russian attack from Transnistria is unlikely in view of the slim chances that Russian forces attempt to besiege Odesa, and an isolated attack would probably collapse in the face of a counterattacking Ukrainian army. Without a breakthrough on the front in southern Ukraine and in view of the status of Transnistria, its military significance probably will be limited to binding the relatively few Ukrainian forces guarding the border.

A protracted Russian war in Ukraine and the possible influx of more refugees would destabilise the economy of Moldova. Poland and its EU allies can counteract this by supporting Moldova with refugee care and intensifying support for pro-European reforms. It is also necessary to effectively promote such changes, which also would counter Russian propaganda. Poland and its allies also could urgently equip the Moldovan army and civil defence, as the prospect of tough resistance may discourage potential Russian attempts to enter territory under the control of the Moldovan constitutional authorities.

Poland unequivocally supports the peaceful reintegration of Transnistria with Moldova. The current Polish presidency of the OSCE may intensify its involvement in monitoring the situation in the region and easing tensions between the authorities in Chişinău and Tiraspol. An instrument of persuasion against the ruling business and political system connected to Sheriff may be by pointing to the risk of suspending the EU-Moldova Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) in Transnistria, which would block export opportunities, harming the company.

The Army, Public Order, and State Security Units of Moldova and Transnistria