The Moldovan Gas Crisis: Causes and Consequences

In October, Russia created an energy crisis in Moldova to stop the reform of its gas sector and to undermine public trust in its pro-EU authorities. Moldova survived the crisis with the support of the EU and Ukraine. On 29 October, however, Moldova concluded a new five-year gas supply contract with Gazprom at the cost of postponing energy market reforms. Poland and Moldova’s EU allies can use this time to help immunise the local energy sector against further politically motivated Russian pressure.

Fot. Vadim Denisov/TASS/Forum

Fot. Vadim Denisov/TASS/Forum

Dependence on Gazprom

One of the main tools of Russian pressure on Moldova has been its gas debt. The domestic operator MoldovaGaz buys almost all of the required supply of around 3 bcm annually from Gazprom. The Russian company controls MoldovaGaz with 50% plus one share, along with a 13% stake held by the separatist Transnistria. The Moldovan government has only 35% of the shares after Gazprom took over a controlling stake in exchange separating the Moldovan debt (around $0.7 billion as of 2021) and Transnistrian debt (around $8 billion). Transnistria's debt is so large because the region consumes about 2 bcm of gas imported by MoldovaGaz, with the local Kuchurgan power plant and the steel mint and cement plant in Rybnits consuming up to 1.8 bcm. As the de facto power in Transnistria, Russia subsidises it with gas supplies without demanding payment, just adding it to the debt. The Transnistrian authorities then sell this gas to inhabitants and enterprises at discounted rates, producing an income of about $500-700 million annually. At the same time, Russia argues that the government in Chişinău, which is striving to reintegrate the state, should recognise the entire debt incurred within the constitutional borders of Moldova.

Moldova’s dependence on Russian gas is deepened by the structure of its electricity sector, in which in recent years only 20% of its needs have been covered by domestic gas-fired central heating plants, and about 3% by renewable sources. About 70-80% comes from Kuchurgan, also owned by a Russian concern. Its dumping prices have led to systemic corruption in Moldova and inhibited the import of electricity from Ukraine, which at times has covered from a few percent to around 15% of the needs. Imports from Romania apart from a few border localities is not possible because Moldova’s power grid is synchronised with the Ukrainian and Russian systems.

Moldova, as a member of the Energy Community, an organisation harmonising the energy markets of the Western Balkans, Ukraine, and Georgia with the EU’s, has committed to implement the Union’s Third Energy Package (TEP), which involves the separation of companies producing, transporting, and distributing energy. However, Gazprom has forced the postponement of the TEP implementation in Moldova, first until 2020 and then until 2021, raising the issue of Moldova’s debt and need to protect its investments, and threatening to raise prices. Gazprom’s aim is to preserve its monopoly and postpone the restructuring of MoldovaGaz.

Energy Crisis

The October crisis was provoked by Russia. The gas contract with Gazprom expired at the end of September. Previous contracts had been renewed each year, and Gazprom did not announce it would change this practice. This was also confirmed by Dmitry Kozak, deputy head of the administration of the president of Russia and his special representative for contact with Moldova. During Kozak’s August visit to Chişinău, he reiterated the Russian hope for pragmatic relations with the government of Natalia Gavriliţa comprised of the pro-reform Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), and with President Maia Sandu. At the same time, Transnistria was preparing for the crisis, as evidenced by Kuczurgan’s four-month stockpiling of coal (as an alternative fuel) and the calm reaction of the authorities to the later reduction of gas supplies.

During the negotiations on a new gas contract, MoldovaGaz and Deputy Prime Minister Andrei Spînu agreed with Gazprom to extend deliveries by two months. Nevertheless, in October, the Russian company raised prices to $790 (compared to $550 per 1,000 m3 in September) and reduced the pressure in the pipelines supplying Moldova to a level that threatened operations. This forced the Gavriliţa government to announce on 22 October a state of emergency in the energy sector. It ordered industry to save gas and switch to alternative fuels. It also enabled the state-owned company Energocom, independent of MoldovaGaz, to find other suppliers, simplifying procedures and allocating about €85 million for orders.

Russia aimed at forcing a postponement of the implementation of the TEP in Moldova and undermining public support for Sandu and PAS, which had announced not only pro-European reforms but also an increase in living standards. The pro-Russia opposition of the Electoral Bloc of Communists and Socialists (BECS) accused the ruling party of deliberately antagonising Moldova and Russia to the point of forcing a drastic increase in gas prices and even the possibility of a lack of it come winter. However, the demonstrations called for by BECS were few, as the public’s trust in Sandu and the PAS is based on the promise of fighting corruption.

Foreign Support and Agreement with Gazprom

Energocom started making ad hoc purchases abroad. Polish PGNiG, together with Ukrainian-American ERU Trading, sold it 2.5 mcm of gas, Dutch-Swiss Vitol another 1 mcm and Ukrainian Naftohaz just over 12.6 mcm. The purchases were possible thanks, among other factors, to the €60 million provided to Moldova by the European Commission for this purpose. Romania also supplied mazut to Moldova’s thermal power plants and Ukraine increased its electricity supply. The countries also borrowed the gas needed to maintain pressure in the Moldovan system, with the Ukrainian operator injecting 15 mcm and the Romanian 1.2 mcm.

Moldova has been able to buy gas from foreign companies thanks to the interconnectors developed in Central and Eastern Europe and Ukrainian storage facilities, which hold about 31 bcm. Under the customs warehouse regime, foreign companies can store gas in Ukraine without paying customs duties and VAT, under the condition that it is taken abroad within three years, which is how PGNiG and ERU, among others, delivered gas to Moldova.

The purpose of these purchases was not to diversify supplies, but to strengthen Moldova’s resolve and negotiating position and induce Gazprom to compromise. Energocom’s orders, however, only partially met Moldova's needs, which amount to 7-12 mcm per day. Moreover, the prices, at around $1,000 per 1,000 m3, were not attractive due to the wider gas crisis in Europe, also exacerbated by Russia’s actions.

The new five-year contract with Gazprom, signed on 29 October, fixes prices to oil and gas benchmarks, so the rate for November is around $450 per 1,000 m3. The protocol to the agreement provides for an audit of Moldova’s share of the debt to Gazprom by 2022 and repayment over the following five years, and until then prohibits restructuring to bring MoldovaGaz into line with the TEP without Gazprom’s agreement.

Conclusions and Prospects

The compromise on the gas price allowed Russia to achieve its main objective of postponing the implementation of the TEP in Moldova. This will hinder the diversification of supply and allow Gazprom to retain control over the Moldovan transmission system. Russia’s actions are unlikely to stop the determination of Moldova’s reformist authorities. However, price increases of up to 240% for gas, 75-100% for electricity produced from gas, and 40-60% for heat may contribute to public disappointment with the pro-European government. Russia will probably be able to use the talks on settling the $0.7 billion gas debt for further political pressure, as Moldova’s total budget of about $2.5 billion a year hardly makes this amount bearable. All this means come autumn 2026 when the current contract expires, the gas crisis may be repeated.

By the next crisis, however, Moldova’s negotiating position should be stronger. It will be able to import about 1.5 bcm of gas per year from Romania’s Black Sea fields after production start there around 2023 via the recently commissioned Iaşi-Ungheni-Chişinău interconnector. Similarly, two-thirds of Moldova’s electricity needs will be covered by the 400kV asynchronous Vulcăneşti-Chişinău line, which is to be completed by 2024. However, the Transnistrian Kuchurgan power plant will remain the main supplier of energy, and its dumping prices will encourage corruption and hamper market liberalisation in Moldova. The EU, in supporting the transformation of its energy sector, should give priority to making it independent not only from Gazprom but also from Kuchurgan. The challenge, however, may be the much higher prices for electricity from Romania.

It is in Poland’s interest to strengthen the Eastern Partnership countries’ security and energy independence from Russia. Therefore, it can lobby for EU support to expand cross-border connections and modernise Moldova’s infrastructure. The mechanism of obligatory gas reserves in the EU would also be a beneficial solution in the event of a new crisis in the EU neighbourhood. This would reduce the risk of sudden price increases, which currently make it difficult for small countries like Moldova to buy from the EU and leave them dependent on Russian supplies.

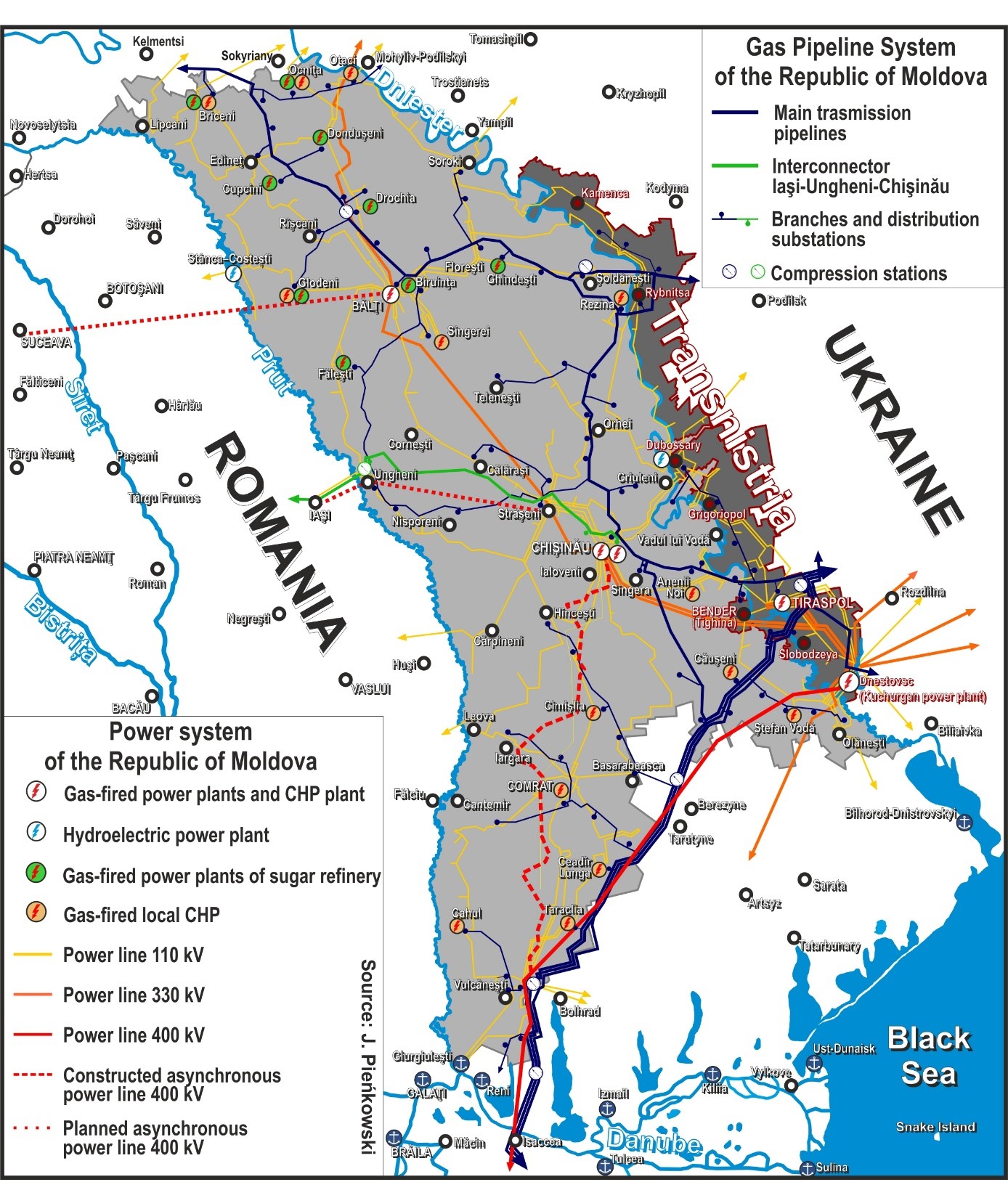

(See map in the Annex below)

The Gas and Power Systems of the Republic of Moldova

Source: J. Pienkowski, based on Moldelectrica, “Starea sistemului energetic al Republicii Moldova,” https://moldelectrica.md/ro/activity/system_state (30.11.2021); MoldovaTransGaz, Schema Reţelelor de Gaze a Republicii Moldova, https://www.moldovatransgaz.md/ro/technical-data/transport-system (30.11.2021).