EU Trying to Reduce Dependence on China

The European Commission’s (EC) term, which ends in June this year, has been marked by a reduction in the EU’s dependence on China, known as derisking. Protecting the Union’s economic and security interests is intensifying with the Sino-Russian partnership and China’s provocations towards Taiwan. Although there still are differences between the EU Member States as to the extent of derisking, the process itself is likely to continue. However, China and some EU countries will seek to ease tensions in European Union-China relations, partly in because of the uncertain outcome of the U.S. elections this November.

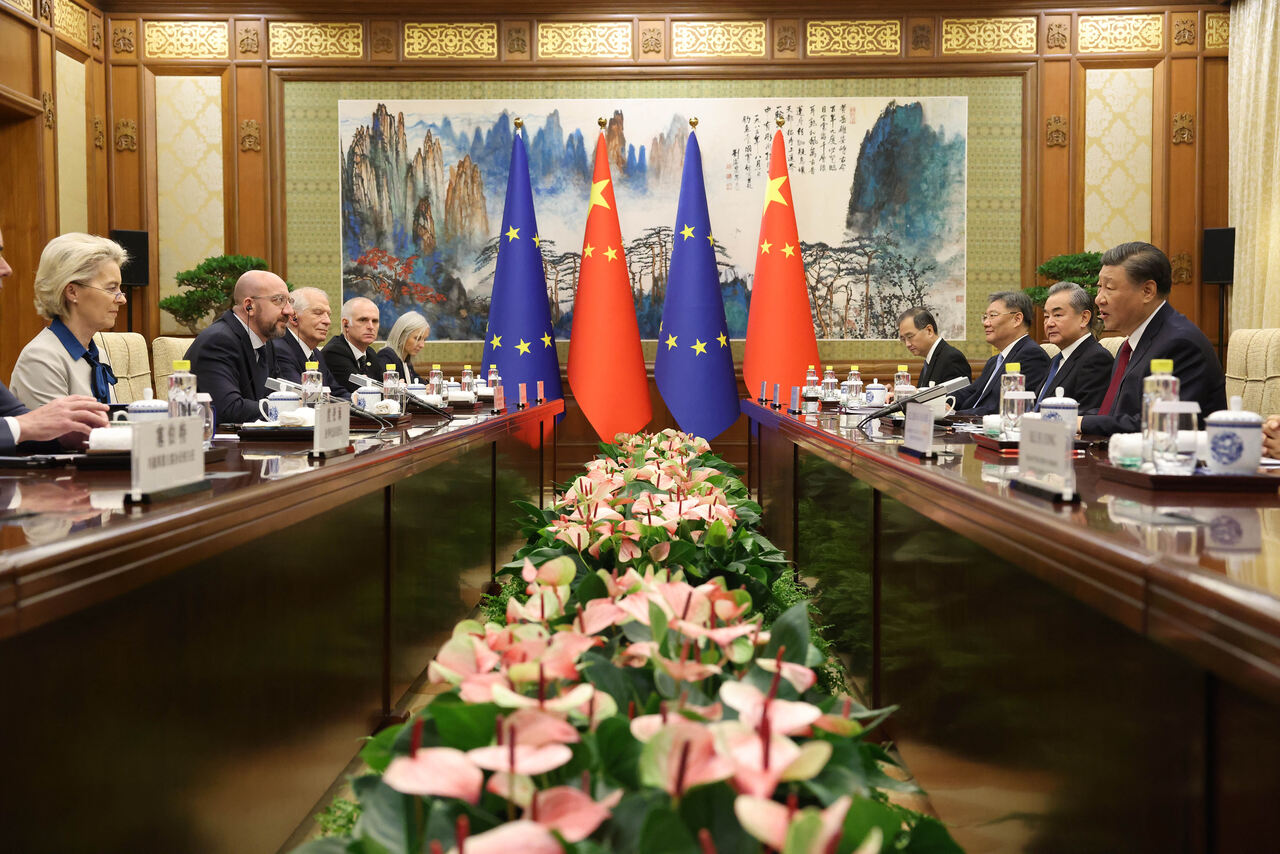

POOL New / Reuters / Forum

POOL New / Reuters / Forum

The last EU-China summit in December revealed the impasse in mutual relations, symbolically confirmed by the lack of a final statement (like after the 2020 and 2022 meetings). Both sides have adopted a wait-and-see attitude ahead of the European Parliament (EP) elections in June this year and the U.S. presidential and Congressional elections in November. Relations are further complicated by China’s difficult economic situation, prompting it to react more forcefully and unfavourably to the EC’s plans and actions towards Chinese entities.

Derisking in Practice

One of the main elements of the EC’s policy is a tougher stance against China’s actions against foreign actors. The Commission has proposed common mechanisms to protect EU companies and the EU market and encourages the introduction of similar tools at the Member State level. Although these instruments are not directly targeting China, it is mainly Chinese policy that is the reason for their introduction, as it is perceived as a threat to EU security, including in the economic dimension. Inbound investment screening (controls on China’s involvement in strategic sectors, such as critical infrastructure) has been in place now for three years at the EU and Member State level (except for Greece and Cyprus). In January, the European Council adopted a position on negotiating a ban on the EU market on the sale of products made with forced labour. In July 2023, a regulation on foreign subsidies distorting the EU’s internal market came into force. It was first used by the EC on 17 February against a Chinese railway company suspected of using subsidies in a public tender in Bulgaria. And another tool, adopted on 7 December 2023, a mechanism against coercion, came into force.

According to the European Economic Security Strategy (EESS), the key to derisking is for governments to work with businesses to identify areas of dependence on China. At the same time, the EC is undertaking investigations into unfair competition from China (some of them have already resulted in the imposition of additional tariffs) and referring complaints to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). As of November 2023, the EC had opened 17 investigations on products from China, including electric cars, PET bottles, and truck tyres. Further EC initiatives from January this year include work on monitoring outbound investment (i.e., examining Member States’ capital exposure in China against the EU’s strategic interests), as well as expanding the assessment of investments in the Union against the broader EU security background. They also include a proposal to intensify the debate on export controls and to strengthen the protection of the research sector dealing with, among other things, dual-use items (civilian/military). Of increasing importance to the EU are the hybrid threats arising from China’s support for Russia. This has resulted in the inclusion of more Chinese companies in the thirteenth package of sanctions on Russia adopted in February this year.

The EC is trying to reconcile its derisking actions with the dominance of Chinese manufacturers in, for example, the electromobility and photovoltaic industries. In October 2023, it published a list of critical technologies for the development of which, among other things, raw materials sourced from China are important in the EU. For example, according to the Commission’s data, 100% of the supply of rare earth elements currently comes from China. Such high dependence is influenced by the limited nature of the EC’s recent proposals suggesting action by Member States rather than the Commission, as well as the suspension in January of a complaint filed with the WTO over Chinese restrictions on Lithuania in 2021. In February this year, during the sixth round of the EU-U.S. Strategic Dialogue, Stefano Sannino, Secretary General of the European External Action Service, emphasised the responsibility of EU Member States to implement derisking. France, for example, is supposed to impose export restrictions in the semiconductor industry from March, but is not doing so because it does not agree with what it describes as the EU’s overly radical and U.S.-like policy towards China. In Germany, on the other hand, there are problems in implementing the China strategy adopted last year due to the opposition of the FDP, a pro-market party in the ruling coalition, as well as high public support for populist parties.

Chinese Optics

China declares its willingness to strengthen cooperation with the EU, regardless of the Union’s allegations related to Sino-Russian relations or China’s escalation towards Taiwan. In February this year, Foreign Minister Wang Yi publicly identified the EU and Russia as the most important directions for Chinese foreign policy. He reaffirmed this in the same month at the Munich Security Conference and during visits to France and Spain. China is trying to prevent a reduction in exports to the EU, important given the problems in the Chinese economy with, among other things, stimulating consumption. To reduce vulnerability to derisking, such as in the electric car industry, China is trying to locate investments in the EU. One of the global leaders in this segment, BYD, is planning to build its first electric car factory in Hungary. Another Chinese firm, Geely, is eyeing a possible investment of a similar nature in Poland’s Izera electric car programme. The Chinese authorities are also trying to encourage EU companies to invest in China in order to create jobs and improve the competencies of Chinese manufacturers and partners. Thanks to previous cooperation of this kind (e.g., in the aerospace industry), some Chinese entities have increased their market share in the country—at the expense of foreign manufacturers—faster than envisaged in the “Made in China 2025” plan. However, China has signalled its readiness to restrict exports of raw materials or products in the event of actions affecting its interests by the EU or its Member States.

The Chinese authorities use “carrot and stick” tactics towards EU countries. They temporarily lift visa requirements or make them stricter (as in the case of Lithuania after its authorities congratulated the new president-elect of Taiwan), and restrict market access (e.g., for alcohol from France), or loosen it (e.g., for Polish, Spanish, and Irish beef and Belgian pork). The EU’s cooperation with China is also supposedly supported by some European political elites who are cooperating with Chinese special services, as undercover operations in Belgium and Germany last December revealed.

Conclusions and Outlook

The EC has emphasised cooperation, competition, and rivalry in its relations with China since 2019, but reducing the EU’s dependence on China has become crucial. The EC’s actions are no longer just defensive, but increasingly offensive. Its motivation is rooted in fears of the negative effects of China’s international policy on EU interests, particularly in the high-tech and green-technology sectors (artificial intelligence, semiconductors, electromobility, renewable energy sources). Threats to EU supply chains arising from close Sino-Russian relations or the possible destabilisation of the situation in the Taiwan Strait are also increasingly important.

The lack of unanimity among the Member States on derisking remains a problem in the implementation of EU policy. Some of them believe that the impact will be too great (e.g., Germany, the Netherlands) or support Chinese political interests (e.g., Hungary). The determination to reduce economic dependence on China is not helped by, among other things, the EP election campaign and the EU’s growing budgetary challenges. The Polish president’s visit to China in June, the German Chancellor’s visit to Beijing in April, or the expected trip of Chinese Chairman Xi Jinping to France should further encourage a softening of EU rhetoric towards China. In this context, it is the responsibility of European countries to maintain the narrative of derisking from the EU’s point of view when dealing with the Chinese authorities. It is also difficult for the EC and Member State governments to cooperate with businesses distrustful of derisking. Many companies are sceptical about greater independence from China, realising the EU’s low potential (compared to the U.S. and China) in industries such as environmental protection, electromobility, and artificial intelligence. They prefer to maintain a presence in the mostly receptive Chinese market. Derisking could be slowed by a greater presence of populist parties in the new EP. The loss of MEPs currently sanctioned by China will strengthen pro-China circles, for example, when taking up the ratification of an EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI).

A constant in China’s policy is communicating its readiness to improve relations with the EU, but on the conditions that it stops emphasising Sino-Russian relations and developing relations with Taiwan. The Chinese authorities will try to use the EU’s concerns about a second Trump term after the U.S. presidential election in November, which likely would include a general tightening of trade policy, as an argument for strengthening cooperation with China rather than continuing derisking. This possibility was pointed out by Wang Yi in February during visits to Munich, Madrid, and Paris. Therefore, in the coming months, China will try to tone down conflicts with the EU to take advantage of a possible conciliatory approach by some EU countries towards China in hopes of a compromise in the context of a possible deterioration of transatlantic relations.

.jpg)