EP, Council in Dispute over EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

Despite an initial agreement reached with the European Parliament (EP), the Council on 28 February rejected the proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which concerns, among others, protection of human rights and ecosystems and supports the implementation of the Green Deal. On 15 March, it eventually accepted the text in an amended version that limits the scope of the companies covered by the CSDDD and thus weakens the potentially beneficial effects of the legislation on environmental and worker protections, among others. This may hinder the adoption of the act by the EP.

KM Asad / Zuma Press / Forum

KM Asad / Zuma Press / Forum

Context of the Proposal

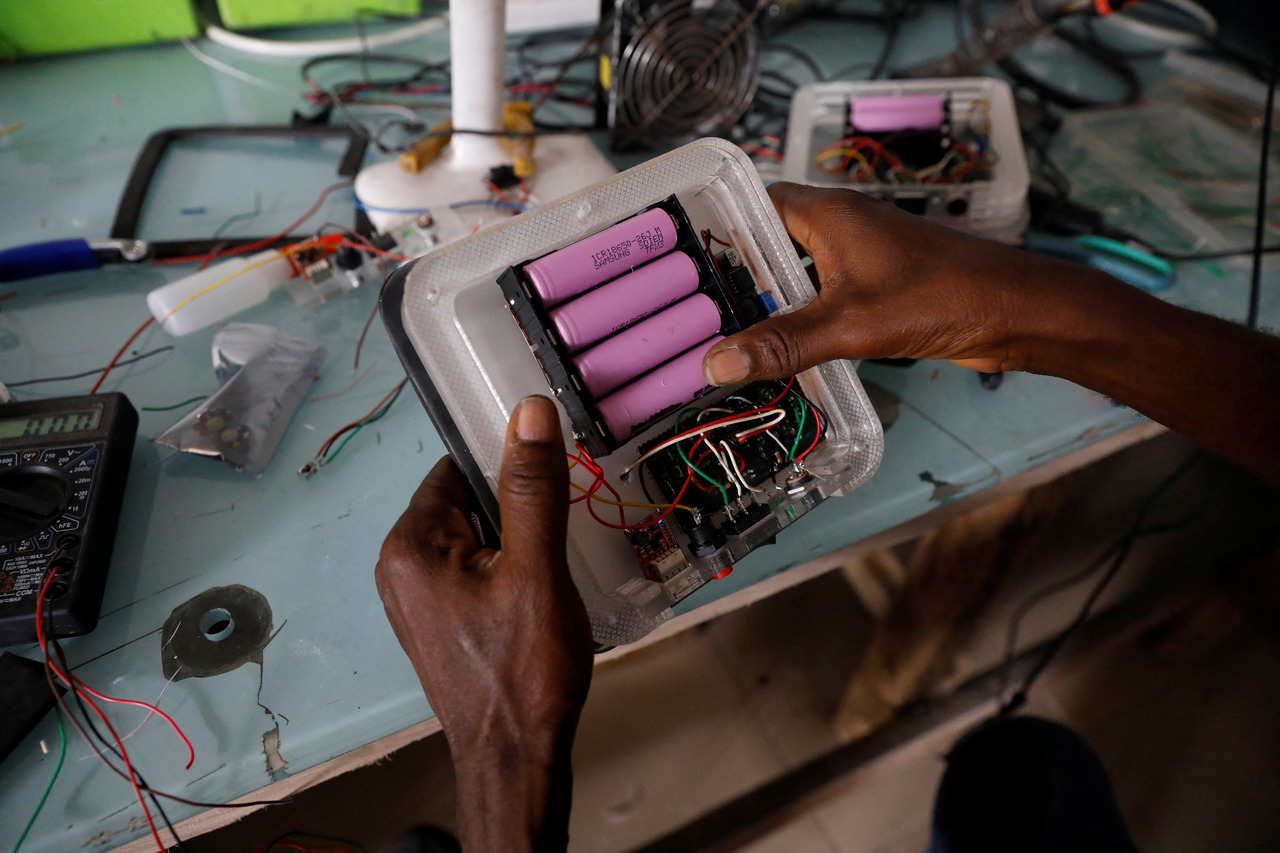

The CSDDD aims to enhance respect for the environment and human rights by major EU and third-country companies and their suppliers. It obliges them to monitor and address negative impacts of their activities, including violations of labour rights, environmental pollution, and deforestation. It is also intended to contribute to improving the environmental and social situation in Global South countries that are suppliers to EU companies. In this way, the EU is trying to counteract the exploitation by businesses of child labour (e.g., in mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo where cobalt is extracted to be used in lithium-ion batteries), non-compliance with environmental standards (e.g., pollution of the Niger delta by European oil companies), or work in dangerous conditions (e.g., in factories in Asia that produce clothes for many European brands).

The CSDDD complements initiatives by the UN, ILO, and OECD by imposing legally binding obligations on companies. It is intended to raise national standards, as only some Member States have their own regulations, including France, Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, but, for example, not Poland. It also extends the EU’s corporate sustainability reporting (CSRD) and disclosure regime for the financial services sector. The proposed solution is important for the EU’s image, as other major economies, such as the U.S., UK, South Korea, Japan, and Brazil, are also working on similar acts.

Implications for Companies

The CSDDD is to apply to companies with at least 1,000 employees and revenues of more than €450 million per year. They will be obliged to identify and prevent the most serious negative impacts of their activities on the environment and human rights, and those most likely to occur. They are also to put in place complaint procedures (e.g., by employees) to be used in case of legitimate concerns about causing such (or potential) impacts and to publish reports on issues covered by the CSDDD. EU states, in turn, are to set up supervisory bodies with the power to inspect, indicate deadlines for remedial action, order the cessation of violations, and impose fines.

In a survey conducted by the Commission (EC), 70% of businesses indicated the need for environmental and human rights due-diligence provisions in EU law. About a third apply them on their own initiative, but this practice is usually limited to the verification of direct suppliers, while violations often occur downstream in supply chains. Opponents of the CSDDD (e.g., Confindustria, the Italian association of manufacturing and service companies) fear excessive obligations and costs to comply with the new rules. These arguments are countered by, among others, representatives of the food industry (e.g., Ferrero, Mars Wrigley, Mondelez), which point to the inconvenience of fragmented rules in the EU and the risk of undercutting standards. Unilever, Ericsson, and Nike see the CSDDD as an opportunity for fair competition by harmonising the conditions of operation across countries. The CSDDD can also have a positive impact on the image of the EU and its companies as caring for the environment and labour rights, which attracts consumers, workers, customers, and investors. In addition, the CSDDD is important for Ukrainian subcontractors of EU companies as they would benefit from better protection, for example during post-war reconstruction initiatives. In contrast, the obligation of EU businesses to verify their partners was perceived by Chinese companies as another way of limiting cooperation with them.

Difficulties with Adoption

The idea of regulation was controversial from the start. The Commission, as urged by the EP, presented the proposal more than six months behind schedule. Trade unions accused it of negligence and of omitting thousands of consultation surveys or failing to include them in monitoring companies’ compliance with due diligence. Some industry representatives, meanwhile, sought to block the initiative altogether and to limit its impact. The scope of regulation was also hotly debated: The EC proposed to extend the CSDDD to value chains, while the Council narrowed this down to the chain of activity, mainly to companies distributing to end customers. In addition, France, supported by Spain, championed the exclusion of the financial sector from the CSDDD (but with the possibility of extending it later), despite opposition from the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, and the EC to such a far-reaching exception.

Although the content of the CSDDD was provisionally agreed in the trilogue by the EC and by the Council and the EP last December, the vote in the Council was postponed several times due to announcements of abstentions by some countries. France, Italy, and Germany were concerned about the regulation imposing too many obligations on businesses. Finland, on the other hand, was hostile to the CSDDD because the act allows for the filing of class action lawsuits, which for the country is a relatively new and rarely used instrument in its legal system. Prior to the February vote, France had proposed raising the threshold for the application of the CSDDD to companies with more than 5,000 employees, which would have reduced the number of companies covered by it by 80%. Austria, Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Slovakia, and Sweden also voted against the CSDDD in February. In the end, the Belgian presidency and the EC made far-reaching changes to the act that led to its adoption by the Council on 15 March, but which were uncharacteristically broad. Normally, once consensus is reached in a trilogue, there is little interference with the text and its adoption is a formality, whereas in this case, the EC and Belgium de facto resumed negotiations on it.

The March amendments narrow the scope of application of the CSDDD. Eventually, the new rules will cover, according to various estimates, between a third and up to half as many companies than the assumed 16,000 (initially they were divided into EU and third-country companies and by sector of activity, with the lowest threshold applied to, e.g., mineral extraction and textile production at more than 250 employees and €40 million in revenue). More favourable arrangements were also created for certain industries, such as agriculture. Moreover, the new agreement reduces the obligations of companies in, for example, waste management.

Conclusions and Outlook

The Council’s withdrawal from the agreement with the EP on the CSDDD could become a damaging precedent that will diminish the EP’s role in EU law-making if such situations recur. At the same time, there is still no certainty that the CSDDD will be adopted, as lowering the level of protection of human rights and the environment tends to weaken support for an act in the EP. According to preliminary estimates, MEPs are split down the middle on whether a weaker law or no law is better. In order to be adopted, the CSDDD should be approved at the plenary session in April, the last one before the EP elections in June. If it fails to be adopted, the fate of the CSDDD will be affected by the outcome of the elections, with the draft either sent for further work, abandoned, or replaced by a new one. On the other hand, if the EP rejects it altogether, a new EC proposal will be required. This means that changes—if any—will enter into force with a significant delay, reducing the benefits of the act.

The adjustments have weakened the potential positive effects of the introduction of the CSDDD. It may be seriously doubtful whether it will really improve the situation of employees of partners of EU companies in the Global South because—due to the definition of the chain of activity in the CSDDD—not every one of the downstream companies must be verified. In addition to this, the protection granted to victims will depend on the national regulations of individual EU states, which may also limit its effectiveness.

It is in the interest of Polish companies that Poland continues to support the adoption of the CSDDD. Polish companies, due to their size and place in supply chains, should not feel the burden of the new legislation and, thanks to the standards of respect for human rights, including workers, already in place, they may be more likely to be selected as partners of large EU companies than competitors from third countries.