The DRC Aims to Enter the Global Electric Car Battery Market

The authorities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo are striving to create a regional industrial base for the production of lithium-ion batteries. This would allow African countries to gain leverage in global markets for new technologies and co-shape value and supply chains. The implementation of the plan will be hindered by technological and political barriers, for example, as competition to China, currently the main producer of these batteries.

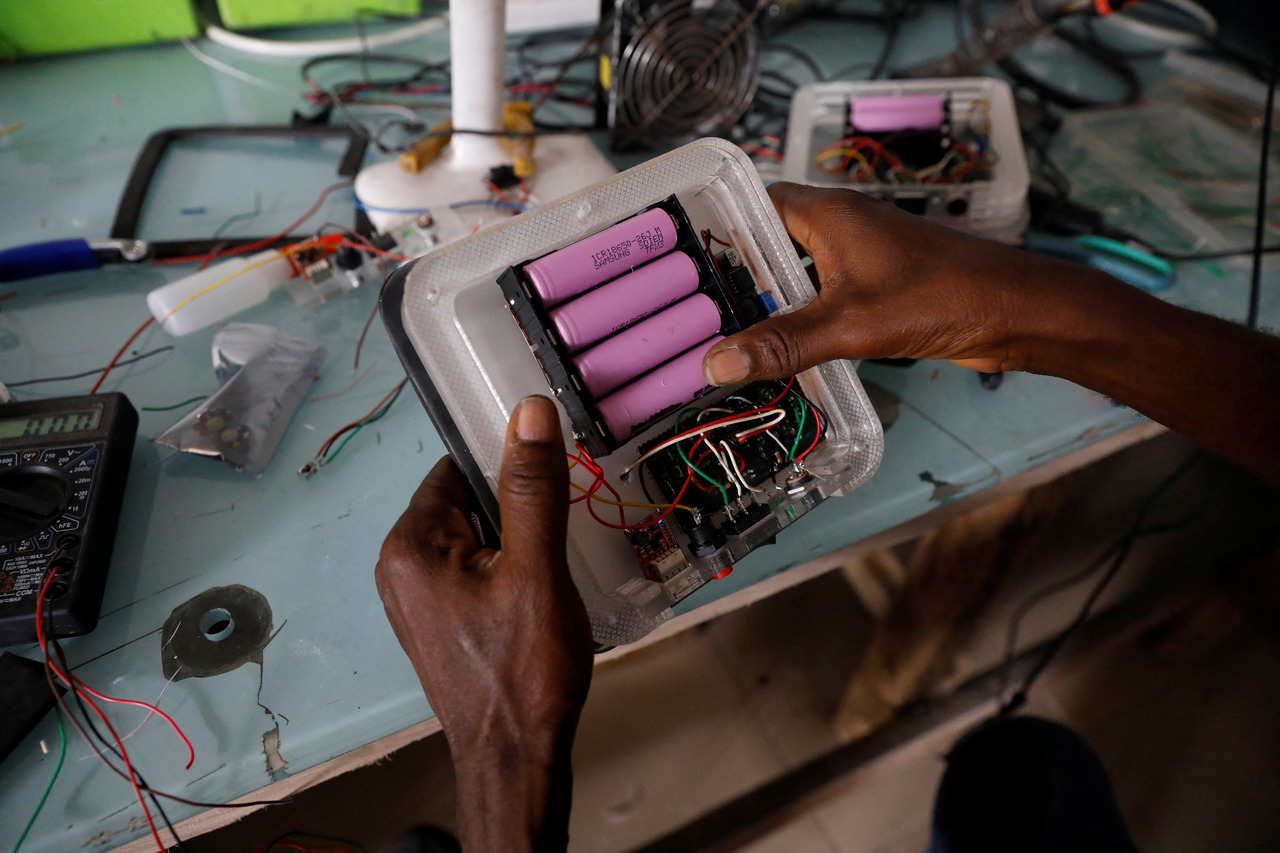

TEMILADE ADELAJA / Reuters / Forum

TEMILADE ADELAJA / Reuters / Forum

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has rich deposits of natural resources, including copper, cobalt, niobium, tantalum, as well as gold and diamonds.. At the same time, it is a poor, underdeveloped country in which, according to the World Bank, 64% of its 100 million inhabitants live below the extreme poverty line. The economic model, preserved since the colonial period and based on the export of unprocessed raw materials, provides the state with only a fraction of the profits from the final product, but fuels corruption and perpetuates the weakness of state structures that has led to armed conflict. Aware of these experiences, the Congolese authorities are determined to take advantage of the global boom in cobalt. Building the country’s own industry for lithium-ion batteries (LIB) would be instrumental in achieving this goal. This idea is promoted by the current president, Félix Tshisekedi, who will run for re-election later this year. He assumed office in 2019 after the first peaceful transfer of power in the history of the DRC, promising to strengthen the economic foundations of the state.

According to IMF data, in the next two decades, the value of copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium production will increase sixfold (to around $13 trillion). A large portion of the projected growth will come from the development of the electric car industry, including the production of specialised batteries, for which demand will increase by 50% by 2030. The Congolese authorities hope that they will be able to account for 10-20% of the global battery production market and, as a result, double the country’s GDP.

The Region’s Potential

With reserves of around 3.5 million tonnes, the DRC holds almost half of the world’s known cobalt deposits. In 2021, about 120,000 tonnes were recovered in the country, which accounted for 74% of the global extraction of the mineral. Congolese cobalt is mainly exported to China, the leading producer of LIBs.

The DRC’s potential in the LIB market is strengthened by regional advantages that can ensure a stable supply chain of key raw materials in the production of batteries: manganese (also from South Africa), copper (from Zambia), graphite (from Mozambique, Tanzania), nickel (from Madagascar, Botswana) and lithium (from Zimbabwe). The DRC already has bilateral trade agreements with some of these countries, and when it joined the East African Community (EAC) in April 2022, it opened up to closer relations with Kenya and Tanzania, which are strong economies in the region. Moreover, on 1 January 2021, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) began to operate, covering 54 countries of the continent and regulating, among others, issues of tariffs in intra-continental trade, economic integration, and innovation. The development of cobalt processing and LIB production in the DRC would be conducive to establishing a regional value chain and diversifying markets on the scale of the entire African continent, opening the way to support from the African Union (AU).

DRC Activities So Far

The country plans to attract investors who will undertake building regional industry for mineral extraction, battery production, and later, electro mobility and clean energy. A consortium of financial institutions to initiate the process is being formed. During the DRC-Africa Business Forum in Kinshasa in November 2021, dedicated to the promotion of this project, the DRC government and others, including the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) and leading continental financial institutions (African Export and Import Bank, or Afreximbank, African Finance Corporation, AFC, and the African Development Corporation, ADC) expressed support for co-financing initiatives. Business representatives also announced their participation, including the Australian AVZ Minerals and German Bosch.

In October 2022, after a year of preparation, the DRC authorities established the Congolese Battery Council (CCB), ultimately the main body to pilot the implementation of LIB plans. The Council is tasked with supporting the DRC authorities in developing the details of the government’s LIB policy, coordinating its funding, attracting investment in this field (especially by Congolese and regional investors) and working with local communities. The latter is to help convince investors that the initiatives do not take place at the expense of human rights.

To increase the chances of implementing the plans and to give them a regional character, the DRC authorities concluded in April 2022—with the participation of UNECA—an agreement with neighbouring Zambia on cooperation and non-competition in the LIB area. The countries agreed on the location of a future industrial base (the provinces of Haut-Katanga in the DRC and the neighbouring Copperbelt in Zambia) and committed themselves to harmonising legislation and jointly attracting investors. Also in April 2022, in Lubumbashi, with German-Japanese support, a Congolese-Zambian research and professional development centre was launched, aimed at educating LIB industry personnel, including in the fields of mechanics and metallurgy. This is to allow the DRC and Zambia to independently maintain and develop the domestic industry in the future.

Continental and Global Contexts

In recent years in Africa there has been a growing desire for systemic changes that will allow the countries of the continent to benefit more from their resources and gain agency in the international arena. This process was highlighted by Pope Francis’ criticism of the actions of international mining companies on the continent during his January visit to the DRC, held in the context of the escalating crisis in the east of the DRC, which threatens to trigger a war with neighbouring Rwanda.

Both the changes in the approach to resources in Africa and the global trend to look for alternatives to Chinese industry worry China. Further, the Tshisekedi government assumes that to improve its ability to manage resources, it needs to limit the influence of Chinese firms. Companies from China now control 15 of the 19 Congolese cobalt mines. In February 2022, a Congolese court ruled against China Molybdenum over control of the Tenke Fungurume mine, which the mining giant bought in 2016 for $2.65 billion. It found the Chinese side had not properly disclosed discoveries of additional copper and cobalt deposits in order to avoid fees that would be due the Congolese state-run company Gécamines. However, the Congolese have so far failed to take over administration of the mine or weaken China’s political influence. The U.S. rivalry with China prompted the former to join the agreement between the DRC and Zambia in December 2022 in which the American side offered its private sector to help build the LIB industry in these countries.

Risks

The success of this and other long-term development plans in the DRC is hindered by the weakness of the Congolese state, especially its vulnerability to crises. To create and maintain the planned production hub, the DRC would have to spend at least $1 billion per year to ensure the availability of energy, currently purchased from neighbouring countries. That requires access to additional financial instruments. Tshisekedi’s term ends in December this year and the prospect of fierce electoral competition, social unrest, and uncertainty in the event of a change of power can scare off investors. A possible armed conflict with Rwanda would most likely spare the far-flung province of Haut-Katanga, but would have a devastating economic and security impact on the country. It also would result in a lack of funds to pay for foreign (e.g., European) expertise and qualified labour, and as a result, would delay plans related to the LIB industry into the indefinite future.

Conclusions

From the EU’s point of view, the development of LIB production in the DRC would be beneficial, as it would decrease the Union’s dependence on supply chains from China, which are vulnerable to crises as evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic or to possible Chinese political and economic blackmail. Therefore, the EU should consider joining with the DRC on the initiative, for example as part of its Global Gateway. The U.S. and Australia’s determination to weaken Chinese influence works in favour of the project’s chances, which, however, are threatened by the volatility of industrial and consumer trends. While the demand for electric cars is growing, it is not certain whether in a decade other technologies, such as sodium batteries, would not replace LIBs. This risk should induce the authorities of the DRC and Zambia to expand the production profile, which, however, would significantly increase the costs of the project. This limits the probability of its success at the assumed scale and thus lowers the risk of competition to others, including Polish LIB producers. However, for the DRC, even limited success in, for example, producing for local markets, would provide a strong impetus for undertaking the structural transformations across Africa that are necessary for development and stability on the continent.