Chinese Financing Impacting Developing Countries

China is not only an important trading partner for developing countries but also an investor and lender. Chinese engagement has become for many countries an alternative to cooperation with the West. However, the activities of Chinese companies increase local levels of corruption and can have a negative impact on the environment and observance of labour laws. In order to remain competitive against China and avoid an erosion of their political positions, Western countries should develop solutions to effectively prevent illicit business practices abroad and thus be ready to prepare more beneficial offers for recipients than those originating from China.

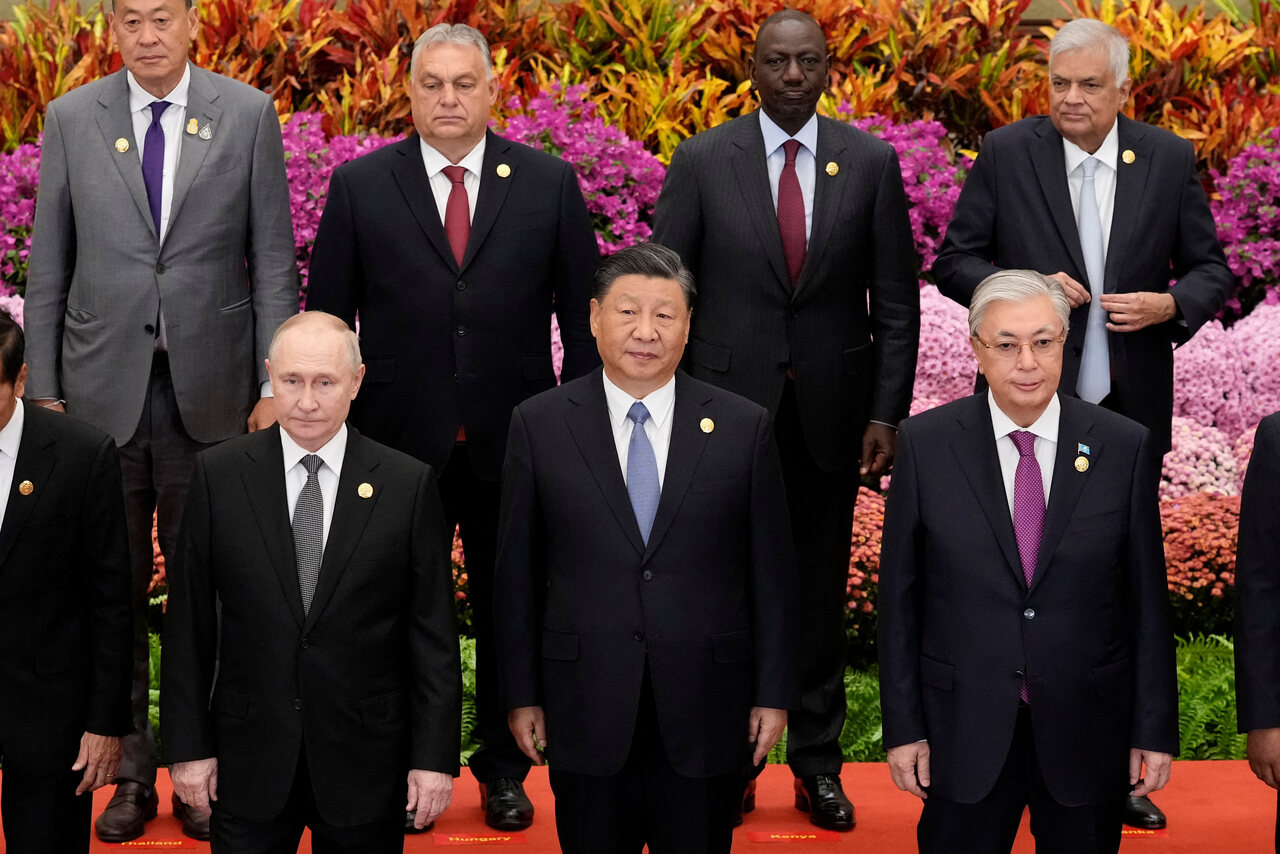

SEBASTIAN CASTANEDA / Reuters / Forum

SEBASTIAN CASTANEDA / Reuters / Forum

As its ambitions have grown, China has been seeking to undermine the position of the West (in particular the U.S., the EU and its close allies in the Asia-Pacific region, such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia) in its relations with developing countries. This is part of an attempt to build a world order in which the U.S. does not play a dominant role. One of the tools China uses to try to achieve this are infrastructure investments, which are not only a business venture but also a foreign policy instrument and closely linked to other forms of Chinese economic presence abroad. Developing countries seek the most favourable solutions, which means that they will be reluctant to decisively side with either the West or China.

Modes of China’s Involvement

The presence of Chinese capital in developing countries takes the form of aid (including preferential loans), loans at market conditions and investment. It also often includes cooperation in the non-financial sphere with the participation of Chinese companies in projects co-financed by China. The various forms of involvement may coincide in a single project. The lack of transparency and public access to contracts, greater state control over the private sector than in the West, and China’s use of its own definitions in the field of development finance make it difficult to distinguish between various forms of its overseas economic activity. While China’s recent engagement has not been growing as fast as before (e.g., the value of new projects under the Belt and Road Initiative has declined and the outbound foreign direct investment flows, while high, are still below the record level of 2016), a long-term growth trend is clearly visible. Internal economic difficulties may cause a further slowdown, but China will remain the West’s most important rival in economic relations with developing countries.

China’s role in development finance is illustrated by the value of China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China loans to public borrowers abroad. Between 2008 and 2021, these amounted to $498 billion, more than 80% of the value of equivalent World Bank loans. China’s role is also growing in the field of investment: according to the OECD, the Chinese outward foreign investment stock increased eightfold between 2010 and 2020 (the latest available data). China is also now one of the world’s most important foreign investors in terms of flows, with Chinese investment less than half that of the U.S. and similar to German, Japanese, Dutch, British, or Australian investment. While much is directed to developed countries, even smaller investments in developing countries can be crucial to their economies. According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) data for 2021, China was the largest foreign investor in Tajikistan, Cambodia, and Niger, and one of the five largest in Kazakhstan, Zambia, Bangladesh, Pakistan.

Consequences of Chinese Business Activities

Projects with Chinese capital are criticised for increasing levels of corruption, disregarding environmental issues and workers’ rights, and raising debt levels through unprofitable investments. These criticisms are grounded in reality, but it does not mean that they are valid for every project. The increasing levels of corruption in developing countries receiving Chinese investment is confirmed by quantitative research. Chinese companies are embroiled in corruption scandals in countries around the world, including ZTE and Huawei (telecommunications) in the Philippines, Solomon Islands, Algeria, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, among others. Chinese business expansion, such as the exploitation of copper at the Las Bambas mine in Peru and the Letpadaung mine in Myanmar, and the cancelled construction of a power plant in Lamu, Kenya, have repeatedly led to conflicts with local populations over environmental damage. There are also reports of local labour laws not being applied to Chinese workers employed by Chinese companies. This occurred in Serbia and led to protests by workers who accused the employer (Zijin Mining Group) of, among other things, taking away their passports, introducing a 12-hour working day, or restricting their freedom of movement.

Rising debt levels, also influenced by loans from China, increase the risk of repayment difficulties among developing countries. China is therefore stepping into the role of “lender of last resort”, saving countries from default. This type of financing, almost absent until around 2012, has reached around $30 billion every year for the past few years, and in 2022, around $40 billion. At least 22 countries have benefited from it, including Argentina, Belarus, Ecuador, Egypt, Laos, Mongolia, Pakistan, Suriname, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Ukraine, and Venezuela. Although the narrative of China causing intentional dependence of their partners by predatory lending for unnecessary infrastructure (the so-called debt trap) is not validated by research, and the projects implemented often serve the local population well, this does not mean that they are economically profitable. As a result, they can be an additional burden, making foreign debt repayments more difficult. In addition, China’s developing competence in emergency lending will open up another field of competition with the West.

The ability to access finance from China reduces the dependence of local authorities on aid and investment from the West. The increased availability of funding is a positive development that can accelerate the pace of development. However, failing to include conditionality in the area of democratisation or human rights will in many cases lead to the strengthening of authoritarian regimes.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Activities of Western states and their business community in developing countries have not always been beneficial to host countries, but the increasing role of Chinese capital exacerbates the above-mentioned problems. Countering China’s influence should include presenting an offer that is favourable to recipient countries, going beyond rhetorical criticism of China’s actions. In many places, attitudes towards the West will be negative, as Western companies have also been involved in corruption scandals, ignored environmental and labour issues, and Western financial institutions have made loans to developing countries beyond their capacity for repayment. The challenge will be establishing effective control of the activities of companies so that they comply with both home and host country laws and do not replicate previous mistakes. In such a situation, it will be possible to show partners that the Western offer is more advantageous than the Chinese.

Cooperation with local authorities can be problematic, especially in non-democratic countries obtaining Chinese funding without conditionality. Western countries will be faced with a choice between lowering standards or giving up competition with China.

China’s presence in emergency lending is potentially dangerous for the West. Such lending has traditionally been the domain of the IMF, which prioritises repayment in resolving debt crises. This is an important element of discipline in the sovereign debt market. The possibility of obtaining rescue loans from China reduces the dependence of developing countries on the IMF and, as a result, could lead to defaults on debts owed to Western financial institutions. This would in turn destabilise the Western financial sector and increase the economic and political dependence of countries taking such action on China.

Poland has no capacity to take direct action to limit the negative consequences of Chinese involvement in developing countries. However, it is advisable to increase funds for development cooperation, collaborate with and promote the Polish private sector, as well as develop solutions that would benefit both Polish business and potential host countries. Poland can also use the experience of its economic transformation and adjustment to deepen economic relations with developing countries. Taking action through the EU is also possible, in particular by advocating increased funding through the Global Gateway initiative.

.jpg)