Cooperation and Peril: Germany Attempts a Policy Balance with China

The COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian aggression against Ukraine, and the resulting disruption of supply chains have intensified the ongoing debate in Germany over the preferred shape of German-Chinese relations. Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s government sees China as both a partner and rival. Reducing dependence on China is challenging due to its scale and the strength of the pro-China business lobby. This unsteady position will cause tensions in relations with partners, including the U.S., and conflicts within the governing coalition. Germany will continue to develop trade relations with China while blocking Chinese investment in critical sectors.

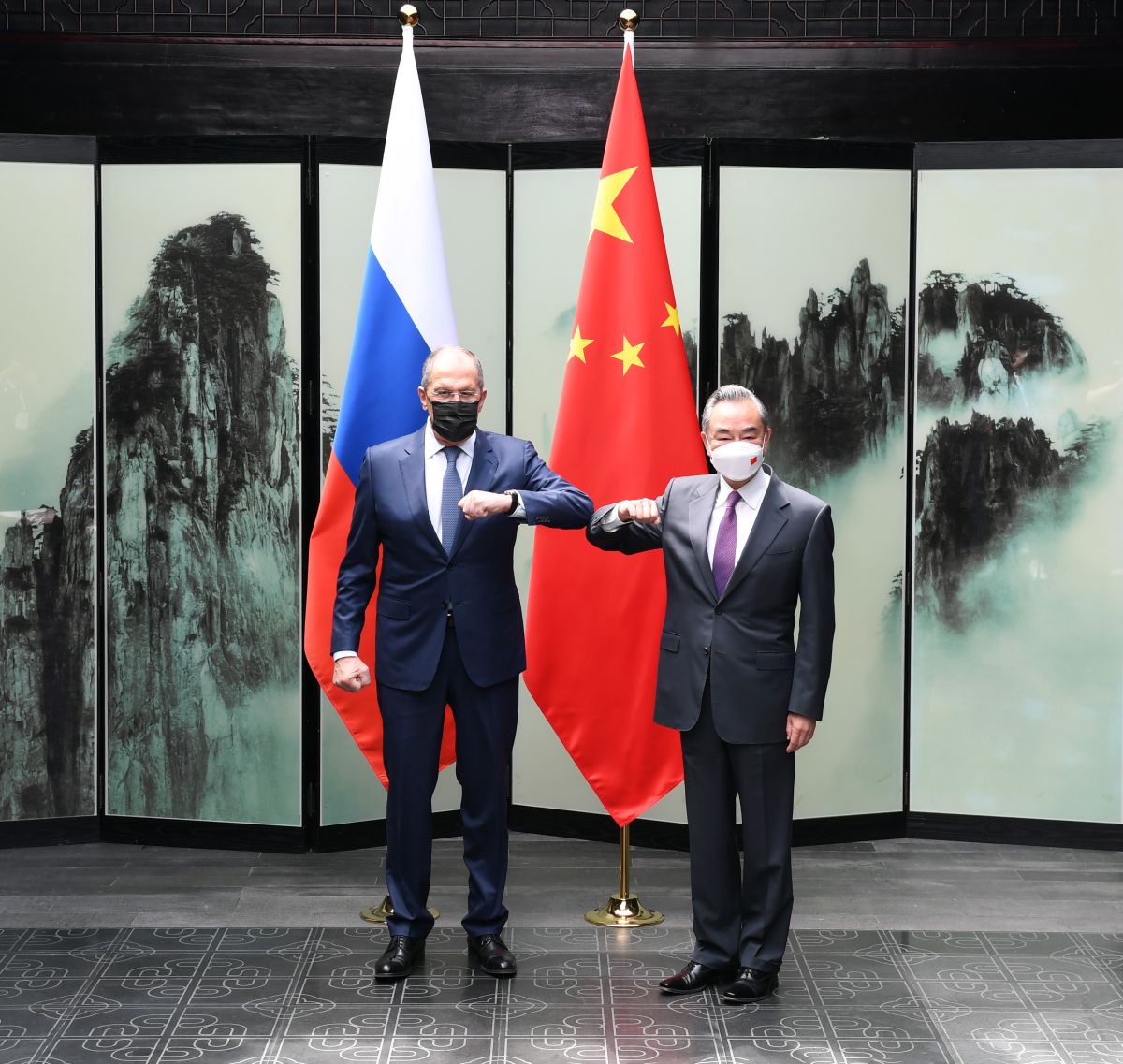

.jpg) THOMAS PETER / Reuters / Forum

THOMAS PETER / Reuters / Forum

Economic relations with China

China is ranked number one on the list of Germany’s trade partners. In 2021, German imports from China, primarily electronics and sub-assemblies, were worth €143 billion, and German exports were €103 billion. China remains the second-largest market after the U.S. for German goods such as automobiles and machinery and equipment. According to a study by the Kiel-based IFO institute, a sharp cut in cooperation with China would mean a 1.4% drop in Germany’s GDP, which would trigger a recession.

An important element of the economic cooperation is investment. Between 2018 and 2021, foreign direct investment by German companies accounted for as much as 46% of total foreign investment in China. The largest investors are companies from major German industries, such as the automotive (BMW and Volkswagen, among others) and chemicals (BASF) sectors.

Chinese investment in Germany is characterised by the linking of economic interests with political goals of procuring new technologies and increasing the degree of dependence of Western economies. Chinese companies are buying up shares in German companies in industries related to, among others, electromobility, pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment. This process has slowed due to increasing political resistance to Chinese business ventures.

In addition to the trade deficit and the link between investment and politics, the scale of dependence on Chinese raw material supplies remains a challenge for Germany and other European countries. China provides 75% of the lithium used in battery production and 45% of the rare earth metals needed for wind power turbines.

Despite the scale of dependence and the risks associated with investing in authoritarian countries, Volkswagen and BASF are planning further investments in China. These decisions are driven by both the desire to maximise profits as well as Chinese lobbying in Germany. Similar to Russia, China uses the influence of former politicians, including ex-Interior Minister Hans-Peter Friedrich. The China-Brücke association he heads is sparking controversy because of its unclear funding sources.

A more cautious stance of concern about managers and lobbyists is taken by some industry associations, led by the influential Federal Association of German Industry. Its president, Sigfried Russwurm, warns both the government and managers against too much or sole dependence on China.

The Political Dimension of Relations with China

The coalition agreement of the SPD-Greens/FDP describes China as a partner, competitor, and in some respects a systemic rival, which is in line with the European Commission’s position. These terms are tougher than those in the coalition agreement of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s last government, which focused on the opportunities China’s development represented for the German economy.

The attitude toward China is illustrated by statements made by Chancellor Scholz, as well as by President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and SDP Chairman Lars Klingbeil. They emphasise the need to reduce the “unilateral dependence” of the German economy on China, but without making a radical break or reducing economic ties with that country. Recognising the dangers of dependence on China, Germany will seek to preserve a globalisation model that allows it to benefit from exports and free trade. However, this kind of strategy may be difficult to implement in the face of growing tensions between the democratic West and authoritarianism.

An additional factor that has sparked debate about the desired shape of relations with China is its increasingly assertive and anti-Western policies. According to a draft of the German government’s strategy towards China, as revealed by media, the priority is to increase resilience to possible Chinese pressure by diversifying supplies and stocking up on raw materials. In the sphere of values, Germany recognises that human rights are unquestionable and indivisible regardless of any cultural differences.

The approach to China has become the subject of controversy within the governing coalition. The cautious course of the Chancellor and SPD is criticised by the Greens and Liberals. They argue that excessive attachment to economic cooperation with the authoritarian superpower is a repeat of the mistakes in policy towards Russia. The Greens, and Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock in particular, have also raised arguments related to human rights violations, the consolidation of power in the hands of Xi Jinping, and the growing tensions over Taiwan.

The balancing between the need to enhance security and technological independence and the desire to further benefit from economic cooperation with China have been reflected in the contradictory steps taken by the government and state structures. On the one hand, despite warnings from departments and ministries, Chancellor Scholz agreed to Chinese shipping company COSCO’s acquisition of a 24.9% stake in a cargo terminal at the Port of Hamburg. The Chancellor’s attitude (he was the mayor of Hamburg earlier in his career) was related to his desire to support Hamburg maintain its harbour by permanently linking such a large shipowner as COSCO to the port, as advocated by current mayor Peter Tschentscher of the SPD. On the other hand, the Economy Ministry blocked the sale of Dortmund-based semiconductor company ELMOS to the Sweden-based Silex, which is part of China’s Sai MicroElectronics group.

Political controversy and public concern also surrounded Chancellor Scholz’s visit to China on 4 November. According to the poll, 74% of respondents view China negatively, and 49% of those surveyed favour limiting economic cooperation with it. Despite these concerns, as in the days of Merkel, the Chancellor was accompanied to Beijing by the heads of German companies hoping for new contracts. One result of the visit was an agreement to use COVID-19 vaccines made by BioNtech/Pfizer in China, but only for vaccinating foreigners. A moderate success for the Chancellor was obtaining vague declarations from Chinese authorities that they are opposed to the threat of using nuclear weapons. As suggested, Minister Baerbock also addressed the need to respect human rights and stressed that any disputes surrounding Taiwan must be resolved exclusively through diplomacy.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The ongoing discussions in Germany on policy towards China are part of a broader ongoing debate within the EU about the future of globalisation and the export-led economic model and the benefits of free trade, from which Germany has derived many gains over the years. Chancellor Scholz is aware that a sharp reduction in ties with China would trigger a recession. Seeking to reconcile the interests of German companies with the need for greater independence and resilience against possible Chinese pressure, the German government will pursue a policy of gradual, evolutionary diversification of raw material supplies and the search for new markets, while maintaining trade relations with China. Economic rapprochement with Southeast Asian countries and the search for new sources of raw materials in Latin America, among others, can be expected. Part of the policy of increasing resilience to possible pressures will also include blocking Chinese investments in strategic sectors related to new technologies. To limit the scale of new German investments in China, Germany is likely to limit the scope of government guarantees for companies investing in the Asian partner, which is expected to transfer risk directly to corporations and motivate them to seek alternative markets.

Politically, Germany will put its hopes on continuing dialogue with China on issues related to Russia's aggressive policies or the climate. If Chancellor Scholz follows this course, it will generate tensions in transatlantic relations, given the logic of the systemic rivalry between the U.S. and China and the expectation that Germany and other EU countries will unequivocally support the U.S. in this rivalry. The willingness to conduct bilateral dialogue with China without the participation of other partners, including France, may also result in an increase in distrust of Germany by some EU countries.