Brazil Engages Unconvincingly in Mediating End of Russia's War Against Ukraine

Since the end of January, President Lula’s government has been promoting an initiative of a multilateral dialogue for peace in Ukraine. Its main objectives are a ceasefire and mitigating the adverse socio-economic effects of the war on developing countries, but also strengthening Brazil’s international position. Lula’s government openly condemns Russia’s aggression but criticises the sanctions against that country and the military support for Ukraine. It maintains it is neutral in the war but also relativises the Russian responsibility for starting it, which undermines Brazil’s credibility as an impartial mediator.

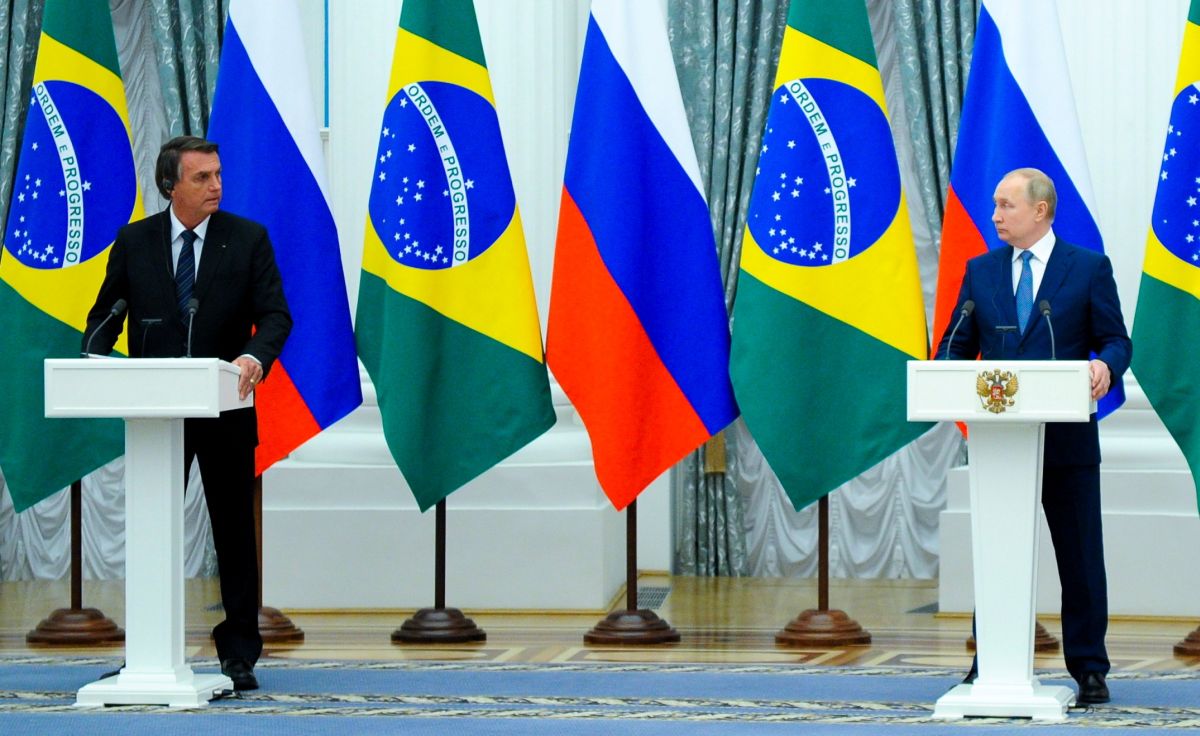

ADRIANO MACHADO / Reuters / Forum

ADRIANO MACHADO / Reuters / Forum

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has led Brazil since the beginning of 2023, is proposing to establish a group of countries not involved in the war that could mediate between Russia and Ukraine. First among this group, he mentions China, arguing that it is the only country able to influence Russia. Together with Brazil, he also points other countries, including India and Indonesia. Lula, however, has not specified the preconditions for negotiations and is currently surveying support for this format. He did not receive much interest in it during talks with the German Chancellor or the presidents of France, Ukraine, and the U.S. In mid-April, he will try to persuade the Chinese leader to his proposal during a visit to Beijing. The Brazilian government’s initiative is part of efforts to rebuild the country’s reputation and international importance after perceiving that the previous president, Jair Bolsonaro, who held power until the end of last year, had led Brazil to marginalisation in the world.

The Brazilian Government on the War

Although Lula, unlike Bolsonaro, openly condemns the Russian aggression against Ukraine as a violation of international law, the government’s position on the war under both politicians are similar and influenced by close Brazilian-Russian relations. The Lula government upholds its declaration of neutrality towards the conflict and emphasises peace talks as the only correct way to end the war. He opposes sanctions on Russia, stressing that the cost mainly falls on developing countries, and argues that its isolation in international forums hinders the dialogue on resolving the conflict. Lula criticises military support for Ukraine and refuses to hand it weapons, arguing that Brazil would then become a party to the war. At the UN, Brazil voted in favour of subsequent resolutions on the war in Ukraine, but did not support the exclusion of Russia from the UN Human Rights Council.

Lula’s government justifies its position by referring to the traditional foundations of Brazil’s foreign policy, for example, universalism, which consists of maintaining relations with all countries, and the principles of external relations set out in the Brazilian constitution, including non-intervention and peaceful settlement of disputes. Declarations made by representatives of the Brazilian government, though, demonstrate that they apply these rules ambiguously and that they relativise the Russian responsibility for starting the war.

In May last year, Lula, then a presidential candidate, argued that Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky was seeking personal publicity and was just as guilty for the war as Russia’s Vladimir Putin. He argued at that time that a clear declaration by NATO that Ukraine would not gain membership would help to avoid a conflict. When he became president this year, Lula suggested that both sides wanted the war to go on. Explaining his peace initiative, he stressed that the mediation effort would be about making Putin aware of “the mistake he made by violating the territorial integrity of Ukraine” and showing the Ukrainian authorities “that it is necessary to learn to talk more, because this would help to avoid war”.

Statements made by Celso Amorim, an influential adviser to the president on international policy and foreign minister during Lula’s first two terms (2003-2010), are another important source of knowledge about the Brazilian perspective. When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Amorim argued that this was a response to NATO’s “expansion” and that since “the Alliance was looking for an enemy”, Putin’s fears were justified. He suggested that European countries’ support for Ukraine showed subordination to the U.S. In March, Lula’s adviser suggested that Ukraine’s and its allies’ alleged rejection of peace talks meant that they wanted to destroy Russia. He stressed that peace talks must consider Russian demands in the sphere of European security. Like other representatives of the Brazilian authorities, he did not refer at all to the peace formula presented by Ukraine last November.

The Impact of the War on Brazil-Russia Relations

Both countries have been linked by a strategic partnership agreement and intense political dialogue since the beginning of the 21st century. The BRICS group has become a special platform for their cooperation, serving as an element of implementing the concept of a multipolar order, including both Brazil and Russia attempting to break U.S. hegemony. Russia’s war against Ukraine has not diminished Brazilian-Russian diplomatic contacts. In June last year, Bolsonaro spoke to Putin by phone and Lula did the same last December shortly before his inauguration. At the end of March, Amorim made a discreet visit to Moscow. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov is due to travel to Brazil on 17 April. In the weeks since the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin, Brazil has not formulated a clear position on whether, as a member of the Court, it would strictly comply with the warrant.

Despite the war, both countries recorded a large increase in trade in goods in the last year. According to the Brazilian government, the value of trade with Russia in 2022 reached $9.8 billion, the highest since 2007 and more than a third higher than in 2021. The increase resulted mainly from imports of fertilizers—Russia has been the largest supplier of the products to Brazil, accounting for almost a quarter of its imports (foreign products satisfy over 80% of the Brazilian demand for fertilizers). The value of trade also increased due to large purchases of fuels by Brazil (especially naphtha and diesel), and in the case of exports to Russia there has been a clear increase in soybean sales.

The impact of the War on Brazilian-Ukrainian Relations

Brazil and Ukraine have had a strategic partnership agreement since 2009, signed during Lula’s visit to Kyiv during his earlier term. However, Ukraine has been a marginal political and economic partner for Brazil. Trade turnover is small and in 2021 it reached $438 million, down from $1.09 billion in 2011.

In March 2022, in response to the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Brazilian government introduced humanitarian visas for Ukrainian refugees (over 400 were issued by February 2023). Zelensky and representatives of the large Ukrainian diaspora in Brazil, estimated at several hundred thousand, have been urging the Brazilian authorities to political and military support. The change of president in Brazil has facilitated intensification of political contacts. In mid-February, the deputy head of the presidential office of Ukraine, Andriy Sybiha, talked with Lula’s advisor Amorim, presenting the Ukrainian peace conditions. In March, Lula had a phone conversation with Zelensky, who invited his Brazilian counterpart to Kyiv.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Lula is not the first Latin American leader to present his vision of bringing peace to Ukraine (for example, the Mexican government presented a ceasefire concept last September). While the initiative is an important self-promotional element of the Brazilian government, it actually consists of proposing a format for talks and urges hostilities to end as soon as possible. The Lula government’s approach, however, de facto favours Russia, which undermines Brazil’s potential status as a mediator.

The cautious language of the Brazilian representatives—most probably intended to not antagonise the parties—is accompanied by relativisation of Russian responsibility for the aggression. Lula’s government is clearly guided by the primacy of long-term interests, considering Russia an indispensable partner in accomplishing the idea of a multipolar world order, so it does not want it to be defeated in the war with Ukraine. In the statements by Brazilian representatives, one can find references to the “legitimacy” of Russian security demands, while the Ukrainian perspective is either unnoticed or ignored.

After the start of the invasion, Zelensky sought the possibility of remote speeches to decision-makers in Latin American countries or forums, but he encountered a lot of resistance. For example, Mercosur in July 2022 turned him down. The Lula government’s stance is an important point of reference for other Latin American countries and for the wider Global South. Even if there are doubts about the Brazilian peace proposals, strengthening political dialogue with Brazil is in the interest of Ukraine and the countries that support it, including Poland. The emphasis in any dialogue with Brazil should be placed on a better understanding of the positions of Ukraine and on overcoming false perceptions that it and its Central European partners are in effect non-sovereign entities, which are just subordinate to others, mainly the U.S.