The Course of Cooperation between Russia and its Latin American Partners

For the past several years, Russia has been strengthening ties with the authoritarian regimes of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, and has developed cooperation with other Latin American countries as an investor in the energy sector, a supplier of weapons and Sputnik-V COVID-19 vaccine, and in other areas. Most Latin American governments have condemned the Russian aggression against Ukraine, but they have not imposed sanctions on Russia. It is in the EU’s interest to persuade its Latin American partners of the validity of the restrictions and to work together to mitigate the negative economic effects of the war.

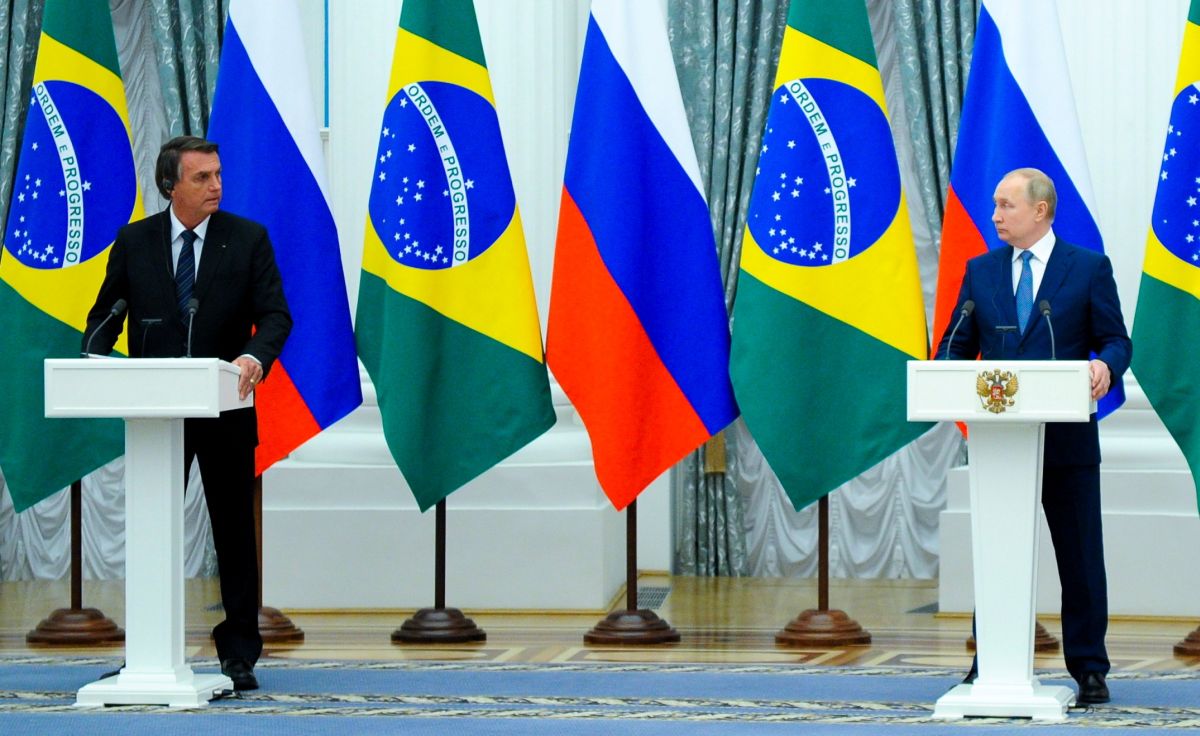

SPUTNIK/ Reuters/ FORUM

SPUTNIK/ Reuters/ FORUM

In response to the Russian aggression against Ukraine, Russia received explicit support in Latin America only from trusted regimes in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. With some exceptions, notably the clearly negative posture by Chile and Colombia, most of the countries in the region condemned the Russian invasion at the UN, but at the same time they have evaluated Russia’s actions and the causes of the war ambiguously. Some of them such as Brazil have criticised the sanctions and attempts to isolate Russia, referring to concepts of neutrality or autonomy in foreign policy as justification for this view. Such a posture is also influenced by the specificity and scale of a given state’s cooperation with Russia, which in the region has sought mainly to develop economic cooperation, recover its superpower status, and limit the influence of the U.S. and its allies.

Key Premises

Russia’s involvement in Latin America has been mainly facilitated by the historical and widespread negative attitude towards the U.S. in the region. From this perspective, the period from 2000 to around mid-2010 was particularly beneficial for Russia. In that time, most Latin American countries were led by leftist politicians. Since 2004, Venezuela, under Hugo Chávez from 1999 to 2013, and Cuba have tried to build an anti-liberal and anti-American bloc that later included Bolivia, Ecuador, and Nicaragua. Argentina and Brazil in particular saw Russia as an important partner in counteracting U.S. dominance in the region and building a multipolar order. In recent years, a further decline in trust in the U.S. was influenced by the antagonistic policy of the Donald Trump administration towards Latin America. This period allowed for even closer relations between Russia and the regimes in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela (under Nicolás Maduro since 2014).

Declining public trust in politicians and democratic institutions has made the inhabitants of Latin American countries susceptible to Russian propaganda and manipulation, which is used to undermine the credibility of the U.S. and the EU, among other goals. Russia was able to effectively influence the public debate and exploit polarisation in society, while the Spanish-language versions of Russian state media—mainly RT and Sputnik—have been expanding their audience in Latin America. They have taken advantage of the freedom to act and of the dynamic growth in the number of social media users.

Russia’s attempts to increase its influence in the region coincided with China’s economic expansion through trade, investment, and credit. For Russia, this reduced the costs of financial support for allied regimes, but it meant rather more competition for political and business influence in Latin America. Russian companies used their advantage in selected sectors, such as arm supplies, which continued based on historical cooperation between the countries of the region (e.g., Peru) and the USSR. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s status as the developer and manufacturer of the Sputnik V vaccine helped it to intensify political contacts with the nine Latin American countries that bought it.

The Outcome of Russia’s Engagement in Latin America

For two decades, Russia has been systematically developing economic relations with the countries of the region. According to UNCTAD data, the value of Russia’s trade in goods with these partners increased from $2.79 billion (0.75% of total Russian trade) in 2001 to $14.6 billion (2%) in 2020. What is important, however, is the dependence on selected products: for example, a fifth of Brazilian imports of artificial fertilisers came from Russia, while Ecuador directed a fifth of its banana exports to Russia. In addition, according to SIPRI, the value of sales of Russian arms to 10 Latin America countries during 2000-2017 (no new transactions recorded since 2018) amounted to $4.68 billion, of which $3.85 billion (over 82%) went to Venezuela. For comparison, the value of U.S. arms deals with Latin America since 2000 is $5.21 billion.

Russia is not a significant Latin American partner in foreign direct investment (with about a 0.2% share by stock value), but it is visible in the raw materials and energy sectors. For example, Gazprom, Lukoil, and Rosneft have invested in the Venezuelan oil industry, although this involvement has been complicated by Venezuela’s constant economic crisis and the U.S. sanctions imposed on the Maduro regime. Rosneft is present in Cuba, Ecuador, and Brazil, among others. Lukoil operates in Mexico and at the end of February took a 50% stake in the Area 4 oil project. In the field of nuclear energy, Rosatom has concluded agreements with Argentina and Bolivia, where it began the construction of a research reactor last year. Russia has also secured its participation in the exploitation of Bolivian lithium deposits. Another example of investment is the space sector: for example, Russia built monitoring stations in Brazil and Nicaragua for its Glonass satellite navigation system.

In the political sphere, Russia has primarily developed cooperation with the internationally isolated regimes of Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. It has supported them diplomatically, including in the UN, and has helped the regimes maintain power and circumvent sanctions. Russia has used these close relations to confront the U.S., such as in military cooperation. In addition to arms sales and technical support, Russia has participated in manoeuvres and carried out provocative demonstrations of force, such as flying strategic bombers to these states in 2008, 2013, and 2018. Nicaragua agreed in 2013 to allow Russian warships to patrol its territorial waters. When in 2019 strong opposition to Maduro arose in Venezuela, Russia sent mercenaries from the notorious private military contractor Wagner Group to protect him. In January this year, amid the escalation of tensions with Ukraine and NATO, Russia suggested it might increase its military presence in Cuba and Venezuela, seen as a provocation meant to ratchet up pressure on the U.S. to limit its actions.

Russia has sought to rebuild its status as a superpower and its global influence primarily by strengthening its relations with the largest countries in the region, mainly Brazil. Both countries have supported each other in their efforts to build a multipolar world order through their strategic partnership, in the G20, and in BRICS, among others. This explains President Jair Bolsonaro’s decision to meet Vladimir Putin in Moscow on 16 February this year, shortly before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and later the Brazilian government’s ambiguous reaction to the aggression (for example, acknowledging the Russian security concerns). The Brazilian leader’s failure to condemn Russia as an aggressor contrasts, for example, with Argentine President Alberto Fernández’s open criticism of Russia’s actions despite meeting Putin in Moscow at the beginning of February. Russia also has been using its state media extensively to promote propaganda about the war and to question the credibility of the rhetoric of Ukraine and its supporters, including NATO members.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Although Russia’s influence potential in Latin America is much smaller than that of the U.S., China, or the EU, it has successfully developed economic and political ties with several partners in the region. The decision to wage war against Ukraine complicates this process, however, as it causes disruption to Russia’s trade cooperation and investment plans in Latin America.

Despite the scale of Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine, most of the countries in Latin America still oppose the sanctions. They see them as measures deteriorating the global socio-economic situation, rather than placing the blame on Russia’s decision to escalate the war or other actions, such as blocking Ukrainian ports. Brazil remains the Russian government’s key partner in the region. It has been openly questioning the legality of the sanctions and opposing initiatives to exclude Russia from various multilateral forums. Brazil also does not see any obstacles to continuing cooperation with Russia in the G20 or in BRICS. However, the restrictions imposed on Russia limit its ability to support authoritarian regimes, which may increase China’s partnership role.

The posture of many Latin American governments weakens the effectiveness of the international pressure on the Russian authorities. It is in the EU’s interest to persuade its partners in the region of the validity and need for the sanctions on Russia, and for the EU to cooperate with them to reduce the global socio-economic costs of the war, for example, in food security. The high public interest in the war in Ukraine in Latin America creates an opportunity to increase awareness of the threat of Russia’s aggressive revisionism, while also strengthening the EU’s credibility and reducing distrust of NATO in the region. In these efforts, Poland may play an important role as a member of both organisations and one of the countries giving the most diplomatic and humanitarian support to Ukraine.