Between Competitiveness and Protectionism: Economic Priorities of the French Presidency

The French presidency of the Council of the European Union will seek to increase the resilience of European industrial ecosystems, support the green and digital transformations, and develop new production capacities. The solutions promoted by President Emmanuel Macron, such as a carbon border tax or minimum wage, are to simultaneously increase the role and competitiveness of French industry and European strategic autonomy. The French presidential elections scheduled for April may make it difficult to achieve these goals.

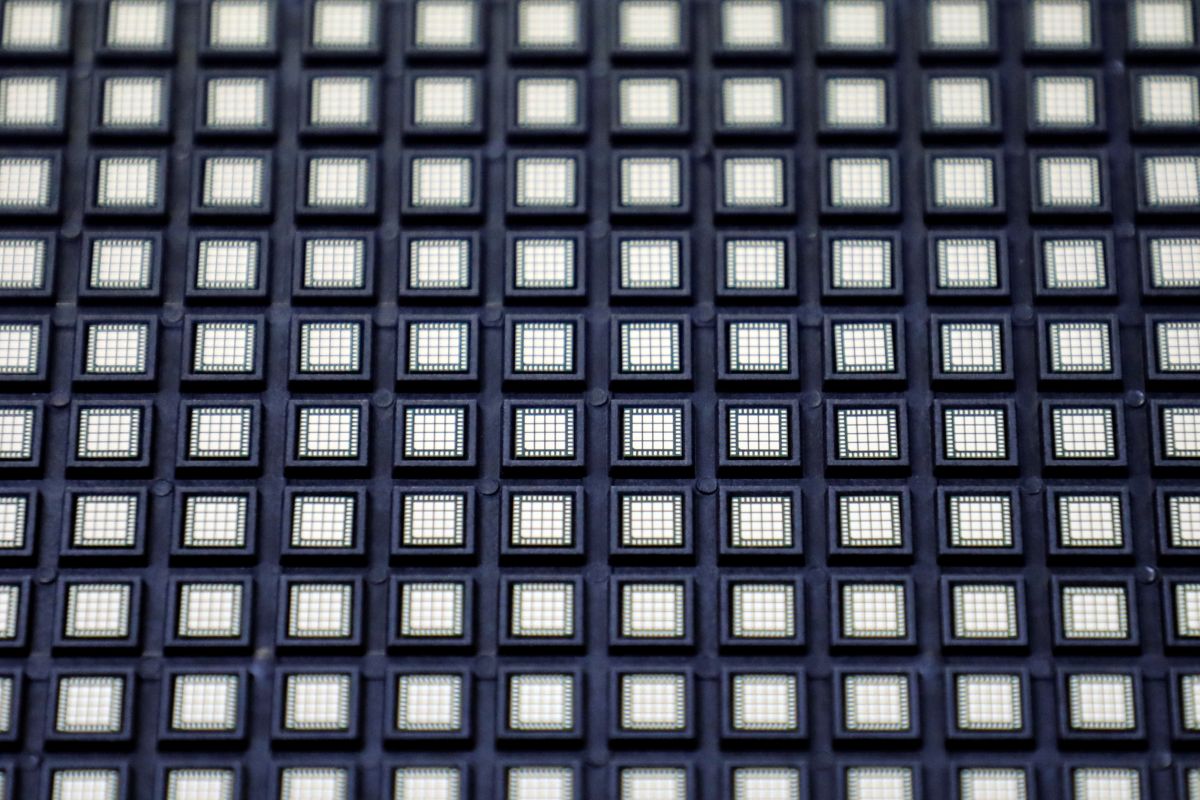

Fot. Reuters/ GONZALO FUENTES/ FORUM

Fot. Reuters/ GONZALO FUENTES/ FORUM

France took over the presidency of the Council of the EU on 1 January. The tough political and economic situation of the Member States caused by the COVID-19 pandemic makes it essential to ensure economic recovery. The EU Member States face meeting commitments to the green transition and reducing the dependence on raw materials import.

Economy and Strategic Autonomy

Digital issues were the main focus during the preparations for the French presidency. For France, a precondition for ensuring the EU’s digital independence and security is to regulate the digital economy, including finalising the Digital Services Act (DSA) and accelerating negotiations on the Digital Markets Act (DMA). The proposed solutions are also expected to have a positive impact on the protection of the privacy of European citizens. The acts adopted by the European Parliament (EP) cover the regulation of digital services in terms of user data security, content moderation, and advertising transparency (DSA). The DMA is to prevent unfair practices of Big Tech companies against business users, eliminate digital monopolies, and strengthen the European single market competitiveness.

France, allied with Germany and the Netherlands, is calling for an increased role for national authorities in enforcing the DMA. Both French digital lobby groups (France Digitale, API, Numeum), aspiring to be a counterweight to global tech giants, and French corporations closely related to the military sector and with the ambition of becoming European champions (Dassault Systèmes, Atos, Thales) are interested in finalising the regulations immediately. Launched in December 2020, the French initiative to build global technology leaders in Europe—Scale-up Europe—brings together more than 200 representatives of leading European companies (including Accor, Airbus, Air Liquide, BNP Paribas, Sodexo) and aims to have 10 technology giants in Europe by 2030 with a total value of more than €100 billion.

Macron announced that he will seek greater public funding and political support for enterprises in strategic industrial sectors through the implementation of Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI), the adoption of the European Chips Act, the EU recovery fund, and the revision of competition rules. IPCEI enables public funding from national or European sources of industrial research and development in strategic areas, such as batteries, semiconductors, hydrogen, raw materials, plastics, and zero-emissions aviation.

France supports the EU initiative on industrial alliances of European companies in a given industry. French corporations participate in most of the IPCEIs. At the same time, Macron aims for greater consolidation of industry and technology so that European corporations can compete with their Asian and American counterparts. The Strategic Forum for IPCEI—the European Commission expert group—was made up of national business groups (including France Industrie). In December 2021, French Minister of the Economy and Finance Bruno Le Maire announced the allocation of €8 billion for joint European investment projects in batteries, semiconductors, hydrogen, and the health sector. The French business lobby (e.g., MEDEF, CCI France, Engie, PFA) is interested in the development of IPCEIs. A significant part of Macron’s France 2030 investment plan (€30 billion) announced in October 2021 is to be financed by IPCEIs and public funds, which reflects the French model of close government-industry cooperation. As part of the support for the “industry of the future”, the government wants to subsidise, among others, the production of small modular reactors (SMR), hydrogen technologies, electric vehicles, and low-emission aviation, hence France’s interest in the EU “green taxonomy” and the rules of granting public aid to the energy sector.

The presidency’s plan includes protectionist solutions for the internal and external market. France strives to establish a legal instrument guaranteeing every worker in the EU an adequate minimum wage as determined by the average national wage, which is a continuation of legal actions initiated by the revision of the Posting of Workers Directive to reduce social dumping in the single market. Macron also seeks to establish a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on the import of high-carbon products. The tax would have an impact on the prices of imported goods, such as steel, cement, fertilisers, aluminium, and electricity production. The introduction of CBAM may be of interest to trade federations, such as FTM (Metalworkers’ Federation), defending the French market against steel imports (China, India).

Challenges

The main challenge for France is to persuade free-market-oriented representatives of the EU (especially European Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager), as well as Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands, to the idea of channelling financial support to industry through the IPCEI. On this point, Macron can count on Poland, Germany, and Italy. The economy ministers of these countries, together with France, approached Vestager in 2020 on competition law reform to facilitate concentrations between undertakings. To gain support for its proposals, France may seek an alliance with Hungary and use the rapprochement in relations with Ireland after Brexit. The future relations within the Franco-German tandem will also be crucial for the six-month presidency.

As for the minimum wage, on the initial stages of the proposal only Denmark and Hungary raised concerns, while Germany decided to abstain due to the change of government. Broad support for the regulation may ultimately tip the balance in favour of this proposal.

The achievement of so many goals may be hindered by Macron’s presidential campaign in France. The presidency of the Council of the EU requires a more consensual attitude, while the campaign favours the promotion of national interests. Macron’s main rival, Valérie Pécresse, is reluctant towards EU-coordinated interventionism. The president of the European People’s Party in the EP, Manfred Weber, has already expressed his support for Pécresse. This may encourage the European Christian Democrats to bolster her candidacy and make it difficult for Macron to achieve his goals.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The presidency programme may turn out to be overly ambitious and impossible to implement. Protracted negotiations on priority issues before the national presidential election may be used by Macron’s electoral rivals to discredit the president’s European policy. The first months of the year will be crucial for the DMA and DSA trialogue negotiations. Postponing the talks until after the presidential election in France will make it difficult to adopt the regulations. Tensions may also appear in relations with the U.S. if the Biden administration perceives the DMA as a threat to American companies.

The French presidency may contribute to strengthening the potential of European industry in the context of global competition. This may lend credence to Macron’s election programme. Industrial protectionism is an important topic in French national politics. The introduction of a carbon border tax can be an effective instrument in lowering carbon emissions. Yet, there is a risk of economic sanctions against European exports.

The challenge for France may be to reconcile the will to increase the EU’s competitiveness with the problems on the domestic market, especially the significant trade deficit. In November 2021, France hit a record trade deficit of €9.727 billion, continuing the trend observed over the last few months. France’s policies that aim to reduce the trade deficit may hinder the EU’s competitiveness.

The regulations supported by France aim at promoting domestic industry, but their implementation is also in Poland’s interest. It is important for Poland to strengthen the EU’s economic sovereignty towards external partners (China, the U.S., ASEAN, Japan) while maintaining the principles of free market and openness to cooperation, especially with non-European democracies. In terms of the minimum wage, it will be important to avoid divisions within the Visegrad Group, as visible with the revised Posting of Workers Directive.