Turkey’s “Coronadiplomacy”: The Pandemic in Turkish Foreign Policy

Coronavirus in Turkey

The country was the last G20 state to officially confirm a coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) case, reporting it on 11 March. The patient was said to have been infected abroad. From there, the infections developed at a rapid pace—by Day 5 after the first positive test, there were 18 more cases reported, and by the tenth day, that number had reached 670. As of 8 April, official data from Turkey’s Ministry of Health showed more than 38,000 infections and 812 deaths. This means that the pandemic in Turkey is rising at a faster rate than even in Italy at a comparable timepoint.

Coronavirus infections have been recorded throughout Turkey, but Istanbul is the epicentre, with 60% of all cases reported. According to the Turkish health minister, Fahrettin Koca, each infected person in the city has infected on average 16 others (compared to 2–4 in other parts of the world). Transmission of the virus is facilitated by Istanbul’s huge population and density—15.5 million inhabitants and an average of 2,831 people per square kilometre, but in the five busiest districts, that ratio is 30,000–41,000 people per kilometre.

Battling the Pandemic Amid Political Quarrels

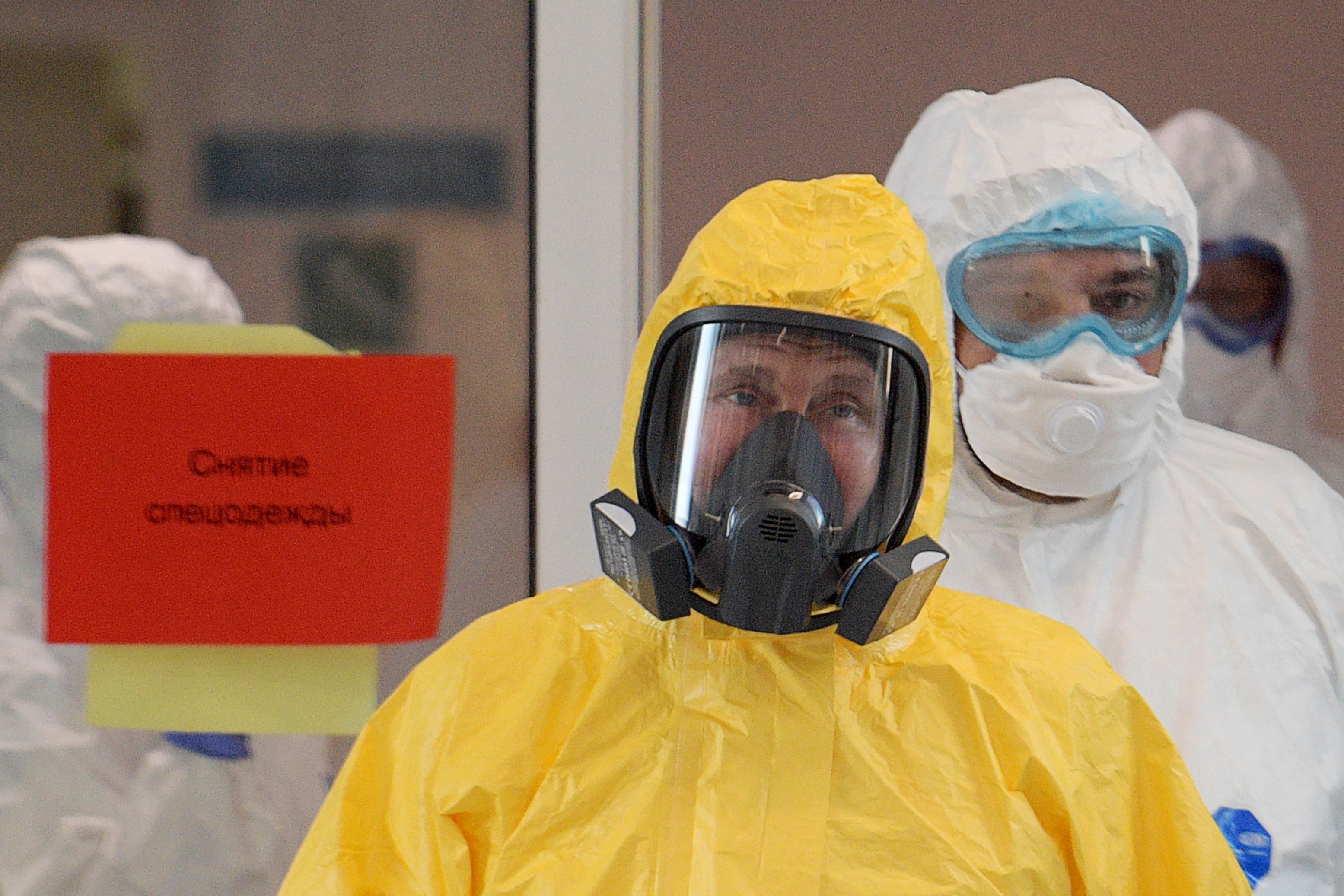

Although the fundamental aim of the Turkish authorities in battling the pandemic has been the protection of Turkey’s economy, the government has gradually introduced more and more restrictions. The priorities were clear in President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s first coronavirus-related speech (18 March) when he focused on the economy. He announced a stimulus package worth about $15.5 billion (around 2% of GDP) in which the government decided to delay the payment of taxes, reduce VAT on domestic flights, increase the lowest retirement benefits, guarantee assistance for the poorest households, and other measures.

At the same time, Turkey is also trying to slow down the spread of infections. On 12 March, the government closed kindergartens, schools, and universities. Then, on 16 March, the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) suspended group prayers. On 21 March, the authorities banned those over 65 and chronically ill from leaving their residences. Further restrictions were added on 27 March and included a travel ban between provinces without governor-level authorisation, the introduction of flexible working hours for bureaucrats, and closing Turkey to international air traffic. On 3 April, the president announced that 30 Turkish provinces would be quarantined and that those violating the social distancing order would be punished. A ban on leaving homes by people under the age of 20, excluding workers, was also introduced.

The authorities’ approach to the pandemic has been widely questioned in Turkey and has been generally praised only by supporters of the ruling camp. Critics have pointed out that, although the countermeasures may seem radical, they were introduced too slowly and are still not adjusted to the scale of the pandemic. They demand a full lockdown for all of Turkey. Also, business groups consider the aid package to be insufficient. The opposition also joined the criticism. Some economists pointed out that Turkey cannot afford a more extensive package because the central bank’s reserves were depleted as a result of defending the Turkish lira during the 2018 currency crisis. Doubts were also raised by the actions of the Ministry of Interior against what it calls “provocateurs”, people who criticise the government and suggest that the pandemic in Turkey is larger than the officials have reported (Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu claimed that about 600 people had been detained thus far). Government plans to give amnesty to prisoners but not political prisoners have also been criticized by the opposition. Yet, the most severe conflict arose between the government and the opposition mayors of Istanbul and Ankara, Ekrem İmamoğlu and Mansur Yavaş, respectively. The conflict is centred on the prohibition by the central authorities of fundraising organised by local authorities to fight the coronavirus. President Erdoğan, who announced his own fundraising campaign under the nationalist slogan “We are enough for each other, Turkey”, accused the mayor of acting like a “state within a state”. His words may have been a suggestion that the local leaders could be removed from office and replaced with state commissars—similar charges have been used by the authorities in the past to remove fractious mayors from office. İmamoğlu complained that the central authorities, despite his numerous requests, did not want to introduce a full lockdown for Istanbul.

“Coronadiplomacy”

Despite the difficult situation in Turkey, the country’s leaders have given aid to 23 countries in their fight against the pandemic, according to data provided by the foreign minister, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu. The Turkish support included a variety of materials and services, such as medicine, medical-grade gloves, masks (including materials for their production), goggles, coronavirus tests, disinfectants and cleaning materials, and disinfection of places of worship. Turkish Airlines also helped to evacuate citizens of several countries (for example, Canada, the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, South Korea, Russia, Indonesia and India) from Wuhan in China.

China was the first country to receive Turkish assistance in the fight against the coronavirus. The number of beneficiaries gradually expanded and included such diverse partners as Bangladesh (assistance for Rohingya), Bulgaria, Hungary, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Yemen, the Philippines, Iraqi Kurdistan (IK), Syria (Idlib), Colombia, and the mostly unrecognised “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus”. So far, Turkish media has focused on three countries: the U.S., to which (according to Minister Koca, Turkey sent 500,000 coronavirus tests, although no U.S. institution has confirmed such a delivery), Italy, and Spain. Local media attention on these cases shows that Turkish assistance also has an internal dimension. It serves the mobilisation of Erdoğan’s electorate, mainly conservatives, by underlining the moral aspect of Turkish policy, and nationalists, by trying to show that Turkey is coping better with the pandemic than Western countries.

Though the Turkish assistance certainly has a humanitarian dimension—some of it is free—it serves the country’s foreign policy goals. First of all, it is aimed at strengthening Turkey’s influence in areas it perceives as zones of its exclusive interest and consolidating its image as a “defender of the oppressed” (Balkans, IK, Idlib). The second goal is to strengthen the message of Turkish decision-makers regarding the revision of the international order along “multipolar” lines. This is especially served by its criticism of supposed inaction on the part of international organisations such as the UN Security Council or World Health Organisation, accompanied by calls for a global response to the pandemic. The third one is an attempt to strengthen Turkey’s relations with its allies (the U.S., Spain, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria) to facilitate its interests vis-à-vis the European Union or NATO. This is indicated, for example, in letters accompanying the aid and sent to the leaders of Italy and Spain from President Erdoğan in which he criticises EU inaction in response to the coronavirus outbreak. By helping highly developed countries, the fourth aim is to win their favour and persuade their companies to relocate production from China. This is evidenced by Erdoğan’s speech of 18 March when he claimed the pandemic could be an opportunity for Turkish producers.

Conclusions and Prospects

The Turkish authorities perceive the coronavirus pandemic as a chance to gain political and economic benefits after it ends. Above all, they count on the humanitarian aid provided during the crisis paying off by increasing the recipients’ willingness to recognise Turkey’s interests. NATO and EU members should be aware of these expectations when they decide to accept the assistance from Turkey.

These plans may be thwarted by the course of the pandemic in Turkey, especially at the current pace of reported new infections. This development is very likely because the actions the government has taken so far indicate that it has adopted the risky assumption that the course of the pandemic will be short. The deterioration of the situation in Turkey may increase the political rivalry between the authorities and the opposition and force the government to focus on internally. It may also increase the government’s tendency to limit freedom of speech and strengthen the central government by further eroding the decision-making of local governments.