Russia and COVID-19

Developments

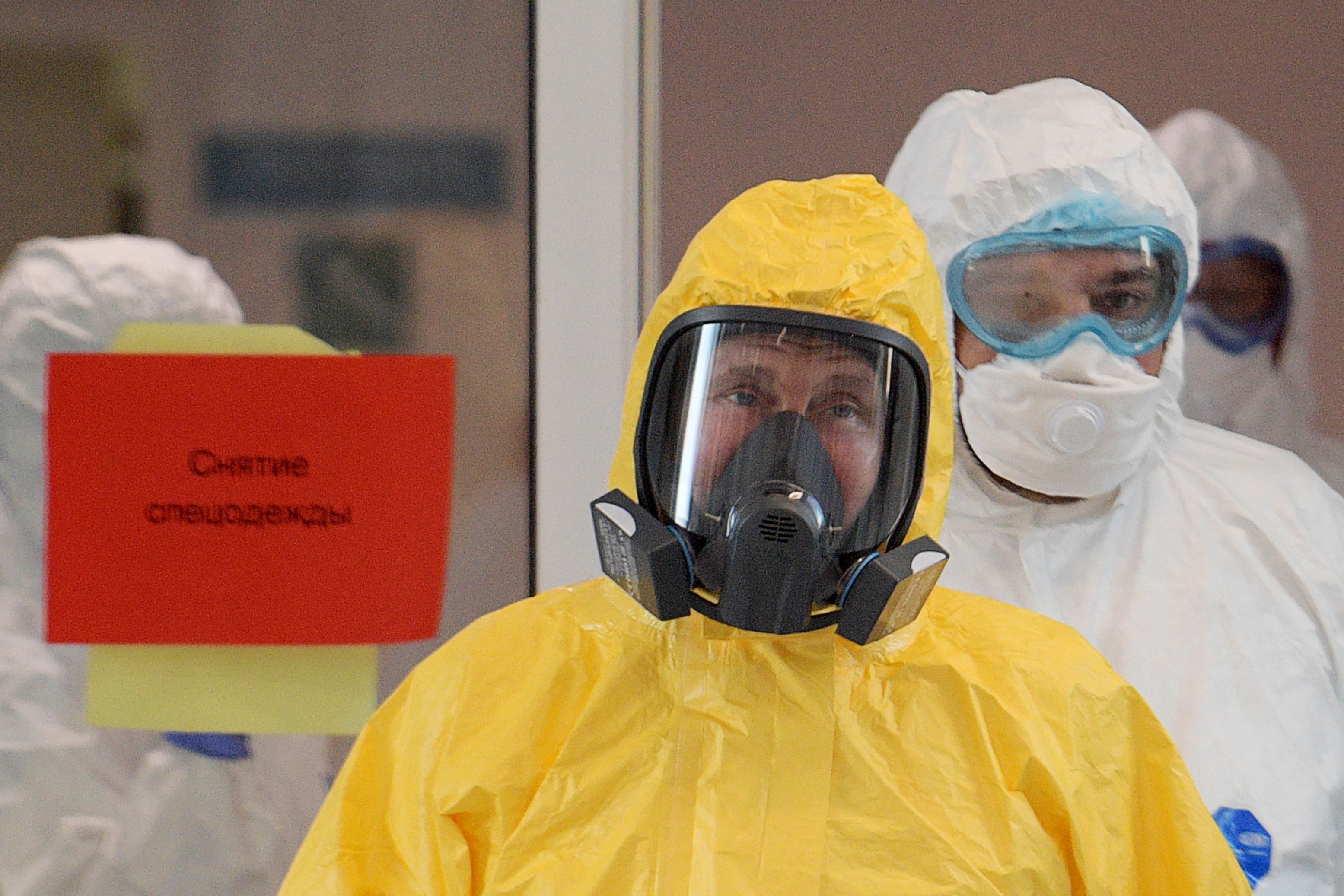

On 13 March, when WHO declared Western Europe to be an epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia had reported relatively few cases (just 45) compared to the purported number of tests performed (94,000) and population (146.8 million). The reason for the small number of infected Russians was explained by doctors as, among other things, the bureaucracy since only one state research centre—Vector in Novosibirsk—was confirming the results, which extended the waiting time for results, and the weaker sensitivity of the Russian tests. This could have resulted in a lower detection rate of up to 100 times. The epidemic in Russia may have developed more slowly as a result of the Russian government’s decision on 31 January to close the land border with China. However, from mid-March, the number of infected increased tenfold (from 63 to 658) in just 10 days, probably as a result of Russians returning from Western European countries affected by the pandemic, mainly Italy and Germany. Restrictions on the population (e.g., assembly ban) were introduced by the Russian authorities gradually. Schools were closed only 52 days after the detection of the first case, the same as in France but later than in Germany or Poland. To stop the growth of the pandemic in the country, residents of Russia have received paid holidays until the end of April, and the regions were left to decide the scale of the restrictions. In the coming months, the pandemic in Russia may take on considerable proportions because, according to polls, most Russians (54%) have not changed their habits (e.g., social distancing). This will be a big challenge because of the country’s inefficient healthcare system, especially outside of large cities.

Political Consequences

The course of the COVID-19 pandemic has had an indirect impact on political processes in Russia. In January, President Putin unexpectedly announced he was seeking changes to the constitution and appointed an efficient technocrat, Mikhail Miszustin, as prime minister. The new head of government was to implement the president’s ambitious plans—social transfers, support for families and the poor. Although the amendments to the constitution suggest that Putin will remain the guarantor of the current balance of power and the system of political and business relations, they did not specify his function after 2024. Probably, the pandemic accelerated the decision to allow him once again to run for the position of head of state (equivalent to a fifth term). On 12 March, parliament adopted an amendment allowing Putin to run for the presidency. The Constitutional Court approved the amendments, justifying them because of “special historical conditions”.

The swift constitutional changes were to be confirmed in a nationwide vote in April, as Putin wanted legitimacy to consolidate his rule in Russia. However, in connection with the pandemic, it was decided to postpone the vote indefinitely, which will make it difficult for the authorities to win public support for the changes (currently 48% of Russians are in favour and 47% against). Due to the pandemic, the celebrations of the 75th anniversary of the end of the Great Patriotic War (World War II) may be cancelled. Some foreign delegations had announced they would attend.

Economic and Social Consequences

The further deterioration of Russia’s economic situation as a result of the epidemic is compounded by the fall in energy prices (with revenues amounting to 40% of the federal budget). During talks at the level of the OPEC+ oil cartel, which attempts to regulate global oil prices, Russia did not agree to Saudi Arabia’s conditions to further reduce the supply of oil. Afterwards, on 9 March, oil prices fell to their lowest level since 1991 and then dropped to below $30 per barrel (Brent Crude). The Russian budget assumes $42.40. According to the influential president of the Rosneft oil company, Igor Sechin, Russia can withstand the price war with Saudi Arabia, which, according to various forecasts, could last from two to five years, thanks to the Russian National Wealth Fund and its $123 billion (as of 1 March). However, the need to finance Russian aid for businesses in connection with the pandemic will put a strain on this fund. An initial support package equal to about $4 billion will not satisfy the rapidly growing needs of enterprises. An assessment of Putin’s current presidency will depend on his ability to control the effects of the pandemic, which is why he has maintained the promise of financial transfers to Russian families (about $5-6 billion a year) and poorer sections of society. However, the weakening rouble will deepen impoverishment. It is not certain whether the authorities will manage to obtain more money faster by taxing richer Russians. The increase in tax on dividends flowing to tax havens (from 2% to 15%), announced by Putin, and the introduction of a new 13% tax on interest on bank holdings over 1 million roubles will not enter into force until January 2021 (and will not be enforced until 2022).

COVID-19 in Foreign Policy

Russia sees the pandemic not only as a threat but also an opportunity in foreign policy. It wants to use the conditions to change the international order to weaken its main rivals, the EU and NATO, and strengthen its position at their expense. By offering visible help to several countries, namely Italy and the U.S. (equipment and doctors), Russia aims to curry favour to lift Western sanctions on it. At the same time, Russia is trying to discredit others, such as Poland, a firm opponent of lifting the sanctions, through disinformation, including the alleged blocking of airspace to Russian aircraft carrying aid for Italy. Russia is also using similar tactics to try to undermine the crisis-management capabilities of the EU and NATO. For example, it is claiming that the reduction of the NATO military exercises Defender Europe 2020 because of the pandemic are really a facade for the weakening credibility of American security guarantees for Europe. The current propaganda campaign using COVID-19 differs from previous ones. It is massive, well-coordinated, and uses both traditional Russian media (RT, Sputnik) as well as trolls, bots, and fake accounts. Since January, the EU’s European External Action Service has registered 110 cases of Russian disinformation regarding the coronavirus. At the same time, Russia is promoting Chinese COVID-19 propaganda suggesting that a U.S. biological weapon is to blame and that only Russia, China and the like are effective in combating the threat.

Conclusions

The coronavirus is rapidly spreading in Russia and the peak is likely only in the coming weeks. In the short term, the crisis will boost Putin as society mobilises around the leader. The president will cite security reasons and countering the pandemic for postponing the nationwide vote on the constitutional changes, and the authorities will increasingly take control of services from residents. In the long run, however, the impoverishment of society may lead to unrest, and this post-pandemic sentiment may weaken support for the party in power (United Russia) in the Duma elections in 2021, as well as affect the outcome of the nationwide vote on the constitution.

The global effects of the pandemic have reduced the demand for oil and Russia will find it more difficult to compete on price with Saudi Arabia. The fall in demand will affect the largest recipient of Russian oil, China, which will limit bilateral economic cooperation despite the common interest in competition with the U.S. With prolonged low oil prices, a recession is ahead for Russia. Therefore, the resumption of talks between producer countries is possible, although they may fail to control the unstable oil market.

Russia’s actions to help selected European countries are aimed at breaking the unity of the EU and NATO. In the future, they may contribute to these countries blocking the extension of EU sanctions against Russia. In the current situation, it will be more difficult for Poland to implement proposals to, for example, strengthen NATO’s Eastern Flank (which includes Poland). Therefore, the fight against disinformation must including limiting Russian RT and Sputnik media in EU countries.