The Katowice Rulebook and Perspectives on Global Climate Policy

The Summit’s Main Outcomes

The most important achievement of the 24th Conference of the Parties (COP24) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held in Poland was the adoption of the “Katowice Rulebook.” It specifies, among others, the structure and methodology of reporting on both GHG emissions and the progress made on climate action. The reports are required from all parties to the agreement every two years, starting from 2024. This will guarantee the transparency of the entire process, enabling verification and comparisons of actions of states party to the agreement.

The Katowice summit filled in the most important gaps in the Paris Agreement, which set the goals and basic guidelines for global climate action. The notion of Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) agreed in Paris did not have specific requirements, namely the elements comprising the form of the declarations and uniform principles guiding them. A universal system was created at COP24, which is a departure from the division into two groups under the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol, the first, developed countries, obliged to take measures to reduce GHG emissions and provide financial assistance, and the second, the developing countries. China’s position turned out to be decisive in this respect, and in the last days of the conference, it agreed to uniform principles for the NDC and reports on activities undertaken.

In addition, the Katowice Rulebook specifies requirements for financial reporting. Developed countries will have to report on planned support of developing countries two years in advance. Setting a new global climate financing target (currently $100 billion annually by 2020) will start in November 2020. The Paris Agreement gives the parties time to do so until 2025.[1]

Apart from the rulebook, Poland, as host of the summit, also offered three political declarations (non-binding, to be voluntarily adopted by some states). The first declaration, titled “Solidarity and just transition,” drawing attention to the social aspects of climate policy, was signed by 55 countries. The second was the partnership “Driving Change Together,” promoting e-mobility and clean transport, signed by 42 countries and 22 other entities. The third, “Forests for Climate,” emphasizing their role in the natural absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, was signed by 69 countries.

Global Climate Policy Challenges

Compromise could not be reached on the clarification of Art. 6. of the Paris Agreement on market mechanisms (trade in GHG reductions). In Katowice, attempts were made to determine how to avoid double booking (in which the reduction in emissions is counted both on the spot and by the country that purchased it) and whether to allow emissions reduction units from the Kyoto Protocol to circulate in the new system. There was also an issue with creating a mechanism to achieve higher emissions reductions on a global scale—a specific share of units would be withdrawn from the market. Brazil, a beneficiary under the Kyoto system and hoping to benefit from the more liberal rules of the emissions reductions market, vetoed the presidency’s proposal of a rulebook for Art. 6. Because potential loopholes could undermine the entire Katowice Rulebook and obscure the system’s transparency, the delegates postponed negotiations on this issue to the next climate summit.

During COP24, the U.S., Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Kuwait objected to the summit conclusions, which were unequivocal in support of the special report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), whose authors indicated that limiting global warming would be possible by quickly achieving climate neutrality. If no action is taken, the increase in GHG emissions will lead to an increase in average temperatures of 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052. The resistance from these four countries was driven by concern that welcoming the report in the COP24 conclusions could in the future become an argument for more ambitious climate action. Taking action at sufficient scale to stop global warming below 2°C or even 1.5°C will be the biggest problem in international climate policy.

The adoption of the rulebook is all the more significant because, since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, global efforts to combat the effects of climate change have faced resistance. The U.S. administration under President Donald Trump has loosened environmental regulations, especially those tightened under President Barrack Obama, and announced the withdrawal of the country from the Paris Agreement. An attempt by Australia to set its emissions reduction target was stopped by its parliament. Despite its positive attitude to global negotiations, China is experiencing a significant increase in GHG emissions. The new president of Brazil announced plans to loosen environmental regulations and withdrew his country from organising the next UNFCCC conference in 2019 (taken up by Chile in cooperation with Costa Rica).

Perspectives on Climate Policy

The lack of compromise on trade in emissions reductions does not mean, however, that trade will not be possible. According to Art. 6.2. of the Paris Agreement, it might be possible without general guidelines on a bilateral basis. In contrast to the very loose rules Brazil has pushed for, this scheme would be less likely to weaken transparency or the global efforts to protect the climate.

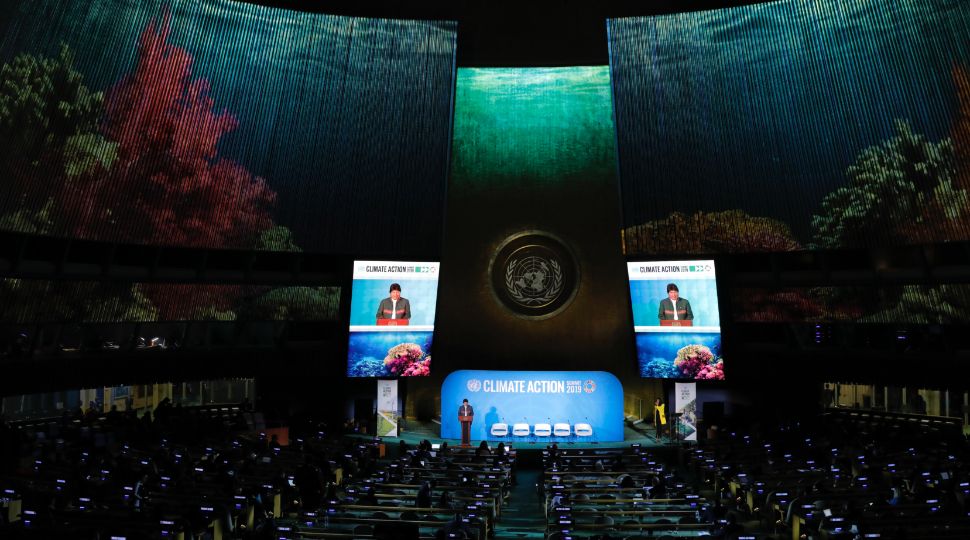

An important role will be played by the climate summit planned for September 2019 and organised by the UN Secretary-General—the New York Summit. It will focus on the topic of increasing the scale of the GHG emissions reduction (termed “ambition”), which, in the face of numerous international climate policy challenges, the discussions in Katowice lacked.

In turn, the EU will continue to strive to set more ambitious climate policy goals with a horizon of up to 2030 or even 2050. The IPCC report findings have shown that the insufficient actions of the parties in reducing emissions will be the basis for increasing the EU commitments. The Katowice Rulebook is also important for the EU because it was the developed countries that promoted a uniform NDC system, as well as monitoring and verification of GHG emissions. For the EU, determined to be the leader of climate action in the world, a strong international system provides the basis for raising emissions reduction targets. In 2019, negotiations on long-term climate policy strategy are taking place at the EU level.

Conclusions for Poland

Until the beginning of 2020, when COP25 will be held in Chile, Poland will hold the COP presidency. 2019 will be a meaningful one for climate policy, since as of 4 November, three years will have passed since the Paris Agreement entered into force allowing Trump to formally notify withdrawal of the U.S. from it. Already, the adoption of a rulebook guaranteeing the unification of regulations for all countries, including emerging economies such as China, may give the U.S. administration grounds to abandon or delay the plan to leave the Paris Agreement.

To seal the success of the Katowice conference, it is worth actively seeking solutions to non-closed negotiation topics. For this, it will be necessary to first conduct a dialogue with Brazil on market mechanisms. Although bilateral trade in emissions is possible, a multilateral system would achieve greater global reductions and provide additional funding for developing countries.

In addition, the declarations adopted at COP24 offer opportunities to promote Poland as the initiator. The most important is the promotion of multilateral cooperation on e-mobility and the just transition. In 2019, the first global e-mobility forum will take place in Warsaw.

Annex: Most Important Elements of the Katowice Rulebook

|

Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) |

All countries will include measures to reduce GHG emissions in their NDCs. Developing countries do not have to set targets that cover the entire economy but they have to strive for them. |

|

The NDC will consist of quantifiable information on the base year, the period concerned (from 2031, all NDCs will cover the same period), scope of actions (e.g., sectors), planning process and national conditions, assumptions and methodology for calculating GHG emissions, the declaration of fairness of the NDC, and demonstrating how it contributes to the collective goal of reducing global warming to 2°C at the end of the century. Parties should use the common GHG calculation methodology provided by the IPCC. |

|

|

Monitoring and reporting |

From 2024, parties will report on emissions and adaptation to climate change every two years, including their NDC. Common methodological guidelines will guarantee their transparency and comparability. States will also be able to point to their efforts related to loss and damage caused by extreme weather conditions. |

|

Flexibility is provided in the preparation of reports for countries that need time to meet the uniform requirements. In that case, however, they must present arguments for why they would meet them later than expected. |

|

|

The NDC and reports will be recorded and published on the UNFCCC website. |

|

|

The rules for the operation of the expert committee on compliance with the Paris Agreement were also agreed. Acting in a non-adversarial and non-punitive manner, it will consist of 12 experts who could investigate parties to the agreement that do not submit NDCs or in a case when data in the reports is suspected to be inconsistent. Then, with the consent of the party, a facilitative dialogue between the commission and the government of the given state may begin. |

|

|

Reviews and revisions |

Every five years, a global stocktake will take place to assess the implementation of the global GHG emissions reduction target. The reviews will consist of the following issues: emissions reduction, adaptation, financial flows, and the loss and damage mechanism. |

|

Issues of transparency will be assessed and reviewed in 2027 and 2028. |

|

|

Financing |

From 2020, reports on financial support will be presented every two years, including planned financing two years ahead. Developed countries are obliged to do so while the others, voluntarily. On the basis of these contributions, a synthesised report should be prepared and ministerial discussion on climate financing should take place. |

|

Setting a new global target for climate finance (currently $100 billion annually by 2020) is due to begin in November 2020 for the period after 2025. The COP21 decisions (when the Paris Agreement was adopted) require that the new target is to be set until 2025 at the latest. |

|

|

Response Measures |

An expert committee was also established to investigate the impact of the implementation of climate action (Katowice Committee of Experts on the Impacts of Response Measures). |

|

Technology transfer |

The operation of the technology-transfer mechanism supporting developing countries with the use of new technologies has been clarified. |