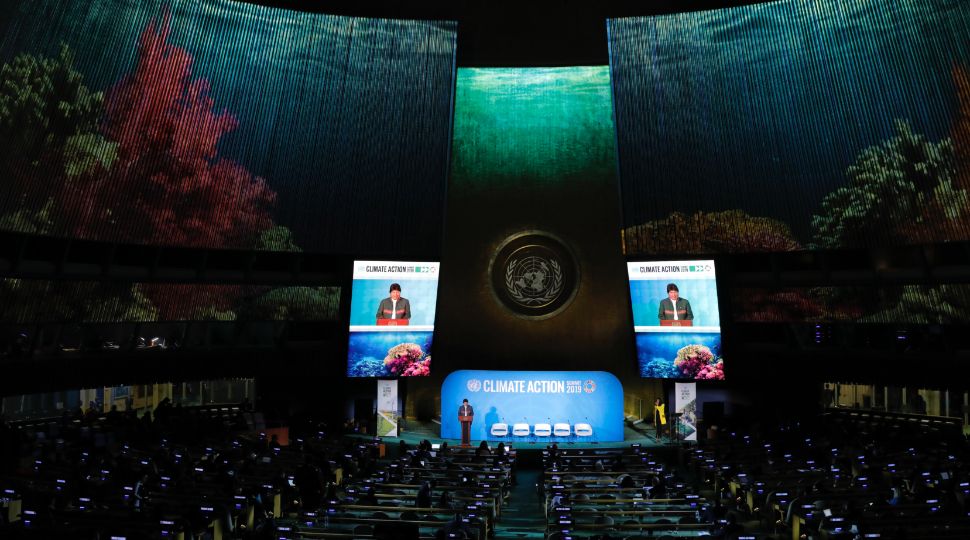

Climate Action Summit in New York - A Political Blockade of Ambition

Why did the Secretary-General convene a climate summit?

Maintaining current goals declared by the states as part of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) undertaken in accordance with the Paris Agreement (PA) could result in global warming of 3–4°C, twice as much as set out in the accord. This would have catastrophic consequences, such as raising the level of oceans, increasing their temperature, limiting access to drinking water, disrupting food production, and forced migration. That is why the UN Secretary-General made the decision last year to organise a summit that would lead to an increase in the ambition to reduce global warming below 2°C (or even 1.5°C), in line with the PA. The summit took place independently of negotiations under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

What new commitments were made at the summit?

A coalition of 15 countries with a smaller share of global emissions declared they would accelerate their reductions of GHG emissions by 2030. However, most of the commitments from industrialised countries were known beforehand, which was why they were not groundbreaking. Many countries, such as France, the UK, and South Korea, have doubled their financial contributions to international institutions, including the Green Climate Fund. Russia ratified the Paris Agreement on the day of the summit. The 47 LeastDeveloped Countries (LDCs) announced a plan to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 (in total, 77 countries have so far declared their pursuit of this goal). Commitments from companies were also significant, including by Allianz, whose assets by 2050 (currently $2.4 trillion) are expected to become zero-emission.

How can the outcomes of the summit be assessed?

The summit was neither a breakthrough nor a failure. The mobilisation of states to make new commitments should be assessed positively. Increasing financial support will help developing countries reduce GHG emissions and adapt to climate change.

At the same time, inaction from such significant economies as the U.S. (President Trump appeared for just 14 minutes of the summit, though he was expected to be wholly absent), Japan, Australia, and Brazil shows that the road to a breakthrough on tackling climate change is still far away. No new declarations have been made by the internally divided EU while China and India have not announced any increases in their emission-reduction targets (the latter, however, declared investments in solar farms). Contrary to prior announcements, Turkey did not ratify the Paris Agreement and did not announce any new actions.

What next in global climate negotiations?

In December, the 25th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP25) will be held in Santiago. The main subject of the meeting will be the conclusion of negotiations on the so-called “Katowice rulebook”, meaning provisions implementing the Paris Agreement. During COP24, compromise on the rules for internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (Article 6) could not have been reached. Progress will be difficult, as Brazil demands the possibility of using units from the previous system established by the Kyoto Protocol, although they operated according to different rules. The official notification of the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement may also negatively impact the proceedings (at the earliest in November this year).

Next year, countries are to submit declarations of national commitments by 2030 in accordance with the Paris Agreement. Then the pressure to increase the ambition of climate action will return.