Slovakia's Pursuit of Better Relations with Russia

Slovak Attitudes towards Russia

In Slovakia, relations with Russia—in contrast to transatlantic relations— are not part of the political consensus. Government policy towards Russia stems from the approach of the three coalition parties—the social-democratic Smer-SD, the Slovak National Party (SNS), and the Hungarian minority party Most-Híd. Of the parties, SNS most favours closer cooperation with Russia. Its leader Andrej Danko is also the chairman of the Slovak parliament and took part in both editions of the International Forum for the Development of Parliamentarism, a conference initiated by the Russian State Duma (the most recent took place in July). He was the only representative of his rank from an EU state to attend, just like during the celebration of the end of World War II in Moscow in May. Danko also questions the need for the economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the EU. This position is also shared by the largest coalition party, Smer-SD, and Prime Minister Pellegrini, as well as his predecessor and now chairman of the party, Robert Fico. The party most critical of Russia is Most-Híd.

President Čaputová, who has rather representative functions in foreign policy, is critical of closer cooperation with Russia and therefore represents a similar approach as her predecessor, Andrej Kiska. Čaputová backs the legitimacy of the sanctions imposed on Russia and, during her presidential campaign in Slovakia, classified the actions of the Russian authorities as a threat to global security. During a visit to Warsaw in July, she stressed the need to maintain NATO unity in its actions towards Russia.

Cooperation with Russia has public support in Slovakia. According to a study published by the American International Republican Institute (IRI) in 2017, 75% of Slovaks are in favour of closer cooperation with Russia in the field of security. Thus, they represent the most pro-Russian attitude among the Visegrad Group countries (although supporters of such cooperation are also in the majority in the Czech Republic at 62%, and in Hungary at 54%). This approach is confirmed by a Eurostat survey from the same year, according to which 50% of Slovaks view Russia positively (the most in the EU after Bulgarians, Cypriots, and Greeks).

Signs of a Slovak-Russian Thaw

On the one hand, the government emphasizes the need to strengthen both Slovakia’s cooperation within the EU and in transatlantic relations (the latter was expressed by Pellegrini’s visit to the White House in May) while, on the other hand, it aims to improve relations with Russia. That is why the prime minister has reacted cautiously to Russian actions directed against his allies in NATO. Slovakia was the only V4 country and one of only eight EU countries that did not expel Russian diplomats in a gesture of solidarity with the UK in reaction to the poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter in March 2018. Pellegrini’s government limited its actions to summoning the Slovak ambassador for consultations in Bratislava and asked for clarification from the Russian ambassador in Slovakia.

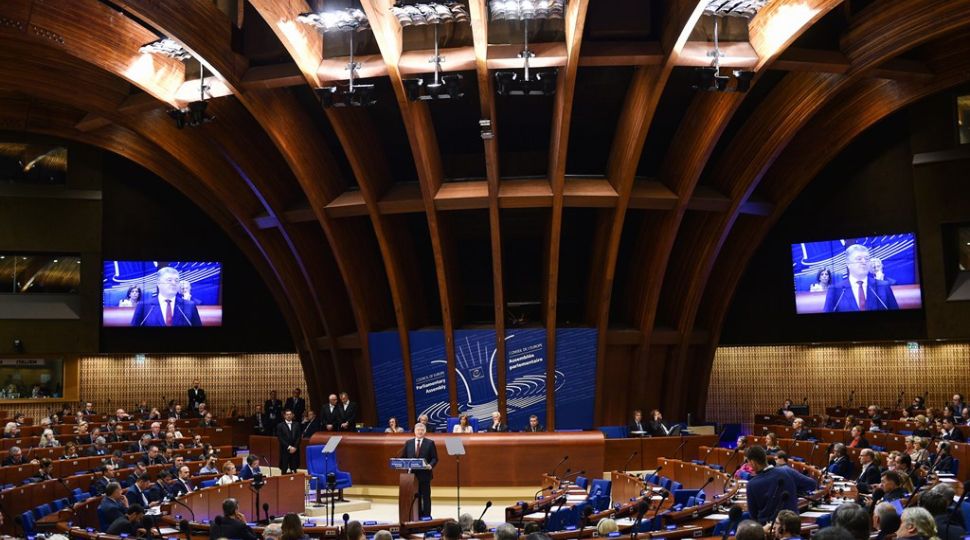

Slovakia wants to expand its communication channels with Russia. In July, most Slovak delegates in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) were in favour of restoring Russia’s voting rights in the body. According to Foreign Minister Miroslav Lajčák (Smer-SD), this change would facilitate dialogue with Russia even though it has not changed its policy towards Ukraine. The Slovak government also emphasizes the need to involve the Russian authorities in solving global problems. Proof of this approach was the discussion in the town of Vysoké Tatry in July with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on issues related to cooperation within the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). An informal meeting of OSCE ministers was part of this year’s Slovak presidency of the organisation and was accompanied by bilateral talks between Lajčák and Lavrov.

The positive attitude of the Slovak government towards rapprochement with Russia does not mean it has an uncritical approach to Russian actions. Lajčák appealed for the release from detention of Ukrainian film director Oleg Sentsov, who in September was released during an exchange of prisoners between Russia and Ukraine. In turn, in November 2018, Slovakia expelled a Russian diplomat suspected of espionage. The countries’ interests diverge, among others, on the integration of the Western Balkan countries into the EU, which is supported by the Slovak government and opposed by Russia.

Economic and Energy Cooperation

As in the other Visegrad Group countries, Slovak-Russian trade has been reviving since 2017. The EU sanctions of 2014 led to the drop along with falling prices of raw materials and weakening of the rouble. In 2018, Slovakia’s trade exchange with Russia amounted to about €5.6 billion. Although trade has picked up in relation to 2016, when it was at its lowest level of €4.07 billion, it is still less than half of what it was in 2013 before the sanctions, at €8.67 billion.

The work of a Slovak-Russian intergovernmental commission is an expression of support for closer economic cooperation. Pellegrini’s presence at this year’s 23rd International Economic Forum in St. Petersburg in a panel discussion together with Russian President Vladimir Putin also served this purpose.

Slovakia and Russia also continue energy cooperation. The effect of Pellegrini’s visit to Moscow was the conclusion of two contracts in this area. The first was signed between the Slovak Economic Ministry and Russian company Rosatom, and the second between TVEL, which is part of Rosatom, and Slovak electric utility company Slovenské Elektrárne. The deals continue deliveries of nuclear fuel to the Bohunice and Mochovce nuclear power plants for the years 2022–2025, with a possible extension to 2030.

Slovakia has been eager to maintain its status as a transit country for Russian gas, which is why it opposed the creation of NS2. However, Pellegrini is withdrawing from this approach as the probability of the completion of NS2 increases. In Moscow, Pellegrini expressed interest in obtaining gas from NS2. In addition, he offered Russia the option of depositing gas. In turn, the Russian government assured Slovak suppliers that gas supplies would continue to be smooth after 1 January 2020.

At the same time, Pellegrini's cabinet is seeking to increase gas transmissions along the North-South corridor. The importance of this was emphasized in the government’s programme for 2016–2020. However, in addition to efforts to diversify energy sources (through the construction of a gas interconnector with Poland, which would ultimately supply gas from the gas terminal in Świnoujście and other locations) Pellegrini expressed interest in gas from the Russian TurkStream gas pipeline.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The Slovak government favours gradual rapprochement with Russia. This is evidenced by the increase in the frequency of meetings at the highest level and the actions of the Slovak presidency of the OSCE, as well as by the increase in trade. This stance is complemented by multilateral instruments of international cooperation, for example, within the Council of Europe and the OSCE. Criticism of the effectiveness of the EU sanctions and the good relations between top-level politicians have been visible in recent years in Slovak-Russian relations. Another stage of rapprochement is Pellegrini’s declarations on gas cooperation with NS2 and TurkStream. This change in approach was caused, among others, by the progress of work on NS2 and Russia’s policy towards Slovakia’s neighbours Austria and Hungary. Slovakia’s new position on NS2 further deepens the split in V4. Now, it is no longer just Hungary that prevents the group from taking a common position.

Following the rapprochement of positions between Slovakia and Russia in the energy sector, it is likely that the two states will further strengthen cooperation, mainly on economic issues. This will be served, among others, by the next meeting of the intergovernmental commission in October in Sochi, Russia. Although the parties that comprise the Slovak government have different views on cooperation with Russia, it is highly likely that the current policy of detente will be maintained since it is also supported by the Slovak For Poland, this means the need to seek partners outside the V4 that oppose a change in EU policy towards Russia.