Return to Multilateralism: The Biden Administration and the UN System

Trump vs. the World

The U.S. president’s policy towards the UN and its agencies was distinguished from his predecessors by far-reaching transactionalism. It was linked to a belief that the high contributions to international organisations by the U.S. due to its greater economic development should directly translate into more American influence in their activities. In return for continuing the current payments, and sometimes even U.S. membership itself, the Trump administration demanded the implementation of precisely formulated reforms or political changes (e.g., ending criticism of Israel, limiting Chinese influence). Usually, the Trump administration presented its ideas in the form of ultimatums that would be carried out if its demands were rejected.

In practice, this tactic failed to force changes, instead resulting in a reduction in U.S. involvement in multilateral cooperation. Within the UN system alone, the U.S. has left the Human Rights Council (2018), UNESCO (2019), and the climate agreement concluded under the aegis of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 2020). In addition, it withheld funding from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA, 2017), the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA, 2018), and the World Health Organisation (WHO), while also initiating its exit from the latter (2020). Trump’s only success was with the Universal Postal Union (UPU). After an announcement in October 2018 that the U.S. would leave the UPU, in September 2019 its members developed new rules for cross-border shipping to replace a system Trump considered as unfairly favouring Chinese exports.

While former presidents from the Republican party took similar steps against UNESCO or UNFPA, the unpredictability of Trump’s other actions (often at the instigation of advisers such as John Bolton) came as a surprise even to his party. The best example was the plan to cut funding for the UNICEF, the UN’s specialised agency for children which enjoyed the strongest backing among the American public for years. The move was blocked by Congress with the support of both Republicans and Democrats.

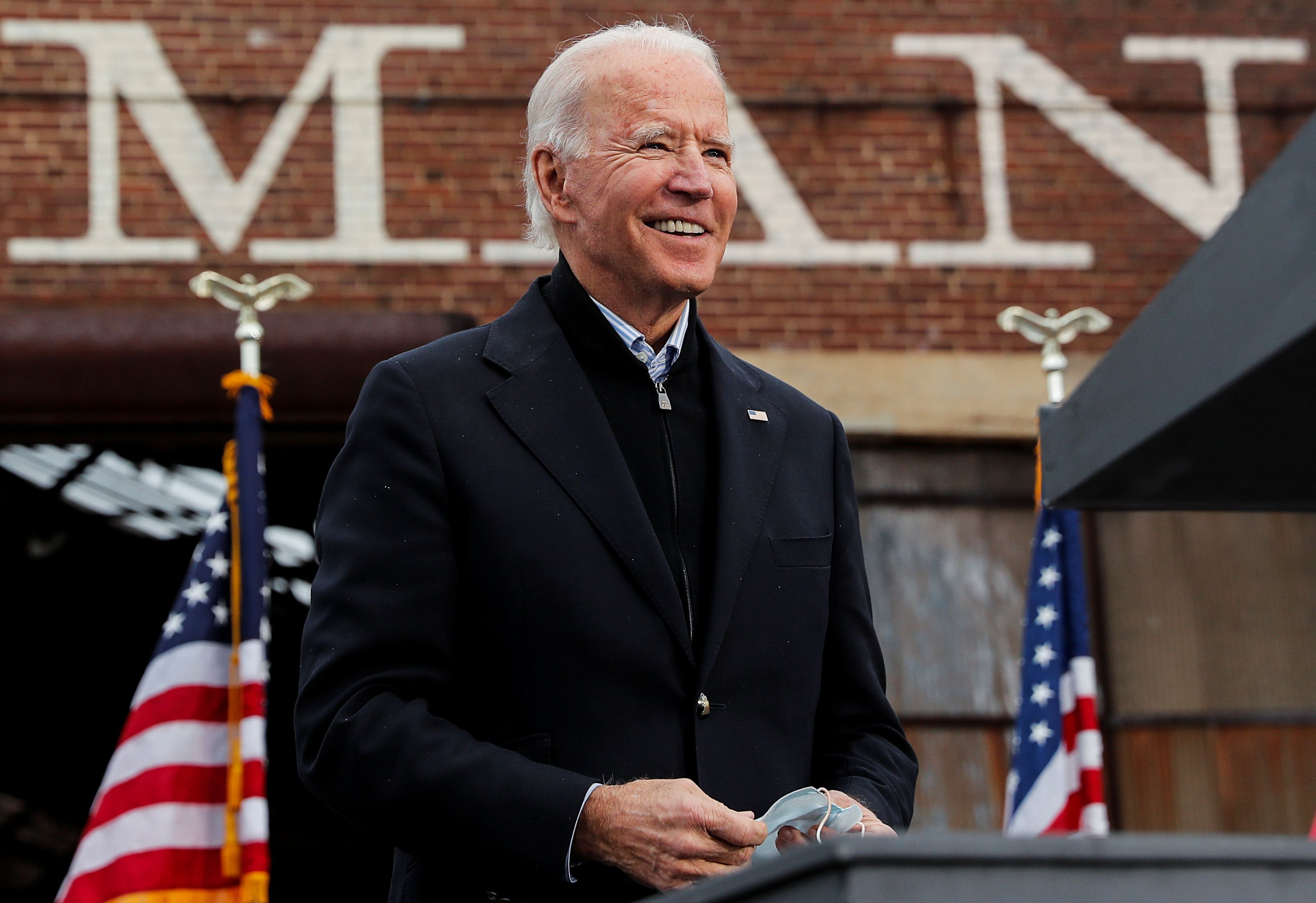

Biden and His New Approach

Biden’s presidency will mean, above all, a change in the style of policy towards the UN and its agencies: giving up the confrontational rhetoric and seeking compromise instead of ultimatums. Biden wants the U.S. to “lead by example” and rebuild its soft power based on promoting democracy, liberal values, and the market economy. He intends for the U.S. to strongly re-engage, in particular in multilateral initiatives in climate, health, and human-rights protection. He announced that on the first day of his presidency, he will return the U.S. to the Paris climate agreement (it would then take effect in February 2021) and he will try to persuade other countries to increase the scale of actions to combat climate change. Biden’s candidate for Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, announced that at the start of Biden’s term the U.S. would withdraw its intention to leave the WHO and restore funding. The president-elect considers the organisation crucial in the fight against COVID-19, although he has expressed scepticism about the WHO’s initial response to the outbreak of the pandemic and seeks to reform it and limit China’s influence in it. It is also realistic to expect the U.S. to return to the Human Rights Council, even in 2021. Biden announced a comeback in December 2019 and later repeatedly declared his will to rebuild the U.S. ability to support and protect human rights in the world, including through international institutions.

It is also quite likely that Biden will restore UNRWA financing. In November 2020, Vice-President-elect Kamala Harris announced that after the new administration is sworn-in, the U.S. would immediately take steps to restore economic and humanitarian support to the Palestinians, especially in the Gaza Strip. While she did not specify whether the aid would be delivered through the agency or otherwise, UNRWA officials say they have been in close contact with Biden’s staff members and are confident that the U.S. will restore funding soon. This is important because the agency is on the verge of insolvency. The U.S. was its largest donor until 2018; although it was replaced by Arab states, they have limited their support in 2020 due to expenses related to the fight against COVID-19. It is less certain that UNFPA funding will be resumed quickly because since 2017 the gap in funding has been successfully replaced by states such as Australia, Canada, and Switzerland. The return to UNESCO is also not obvious. It would require changes to laws by Congress and could adversely affect relations with Israel, which is critical of the organisation.

The general U.S. administration attitude to the United Nations will also change. Biden’s staff has a separate team to deal with American politics in the organisation. Linda Thomas-Greenfield, who is Black and a diplomat with extensive experience in relations with Africa, was nominated as the U.S. representative to the United Nations, where she will help strengthen the American position and rebuild the confidence of developing countries. It is possible that the U.S. will settle outstanding pledged contributions to peace operations, which amount to about $1 billion after Trump’s term in office. In 1999, Biden co-authored a law under which the U.S. repaid a similar amount of similar debt. He also supports UN peacekeeping operations on the idea that they reduce the need for the U.S. to engage its forces to ensure stability in conflict regions.

Challenges

A mere U.S. return to organisations it has left or planned to leave under Trump and an increase in financial support of them will not be enough to strengthen the American position in the UN system. It will be necessary to restore the credibility that has been damaged in recent years (e.g., in terms of climate action) and to present a reform programme for elements of the system that have not always worked properly, such as WHO, and that is convincing for the broadest possible group of countries. It will also be important for the Biden administration to develop a strategy on how to make U.S.-promoted values and initiatives attractive again to most African, Asian, and Latin American countries, like it did in the mid-1990s. A more traditional approach to multilateral diplomacy may help the U.S. develop a common stance on various issues with countries sceptical of Trump’s actions, especially in Western Europe. However, a challenge will be China’s stronger position in the UN system, which it has taken advantage of in recent years with the decline in U.S. involvement in multilateral diplomacy and good relations with some African and Southeast Asian states to increase its political influence. U.S. actions will also be counteracted by Russia, reluctant to American leadership and advocating a polycentric international order, as well as countries such as Belarus, Iran, Cuba, Nicaragua, Syria, and Venezuela, fearing increased pressure for democratisation and internal changes.

Conclusions

Biden’s presidency will create the conditions for at least a partial restoration of the U.S. position in the UN system. This will be beneficial for Poland, which considers the UN one of the main pillars of the present international order and, at the same time, remains a close ally of the U.S. It will give the opportunity to undertake new joint initiatives, for example, to improve the WHO’s ability to respond to threats to public health, improve the performance of UN peacekeeping operations, and protect the climate in a way that would be beneficial to economic development. In connection with the participation of the Polish contingent in the UN mission in Lebanon (UNIFIL), the possible settlement of financial arrears by the U.S. to the UN would also be positive from the Polish perspective.

Poland’s support will be important for the possible return of the U.S. to the Human Rights Council, and especially to UNESCO. In the first case, Poland will be able to support the U.S. in a secret ballot in the UN General Assembly, and in the second, it may participate in the preparation of a recommendation by the UNESCO Executive Board (where Poland’s term ends in 2023) and vote in the General Conference of this organisation.