Gazprom’s Struggle to Complete and Control Nord Stream 2

The Challenges to Completing NS2

The main issue for Russia and Gazprom has been the delayed construction of the pipeline. According to the initial plans, it should have been completed by the end of 2019, but it was delayed by a late permit for construction in Denmark’s exclusive economic zone by the Danish Energy Agency (DEA). The permit was issued on 30 October 2019, when around 85% of the pipeline had been completed. However, construction was halted soon after when the U.S. president signed on 20 December 2019 the National Defense Authorization Act, in which Congress included sanctions. The act stipulates sanctions on the owners of vessels involved laying pipe for NS2 at a depth of 30m or deeper and on entities facilitating such works, such as insurers, which are a DEA requirement. Due to the risk of sanctions, the key contractor, Swiss company Allseas, which has specialised pipelaying vessels, withdrew from the works immediately. The risk of sanctions means the Russians cannot count on foreign partners and must complete the remaining 160 km on their own.

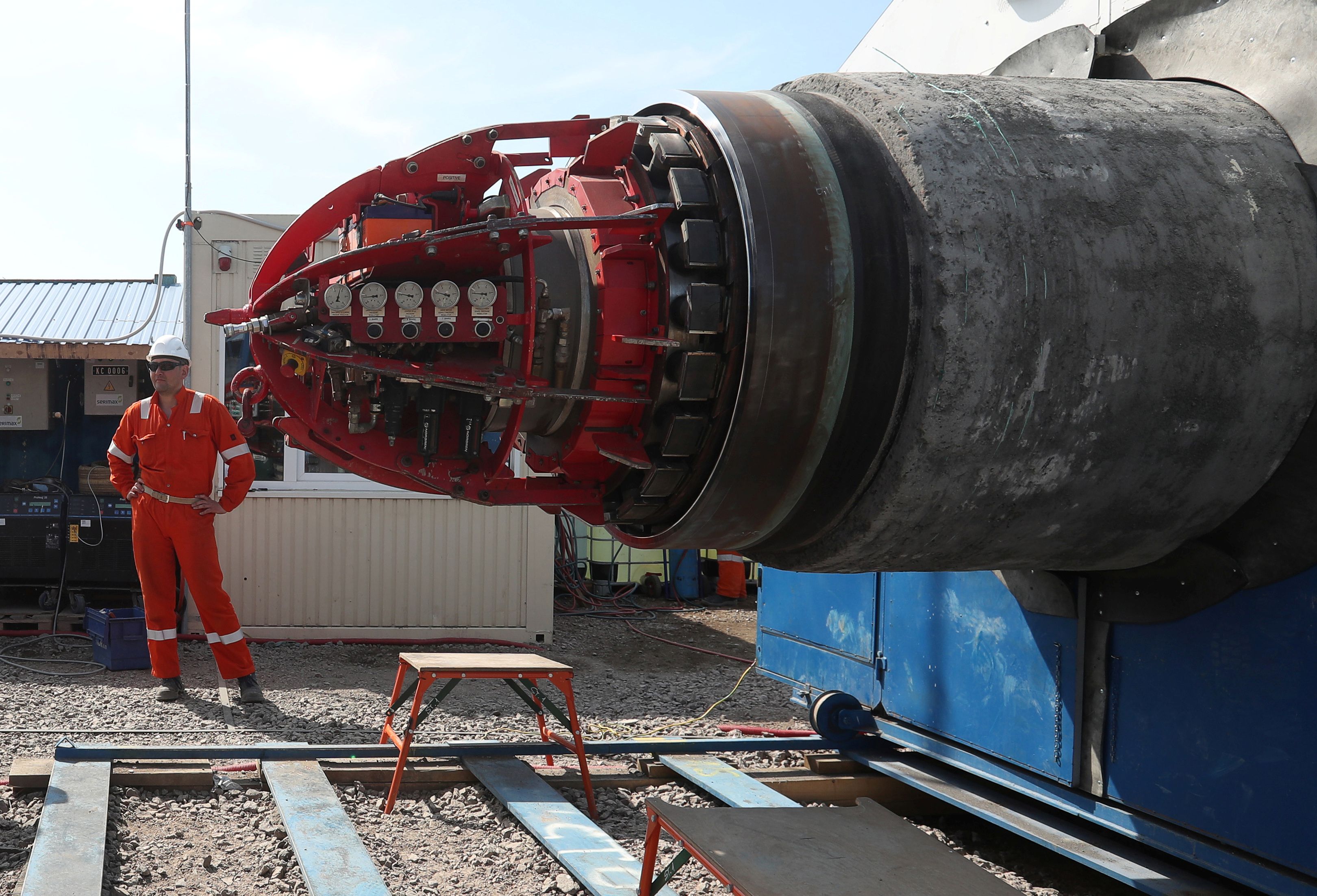

Unlike Allseas, Russia does not have modern and efficient pipelaying vessels. The use of some of them, like those owned by Russian company MRTS, is complicated by the fact that their position at sea is maintained by anchors—forbidden under the DEA environmental permit since the anchors could release chemical weapons that were sunk in the Baltic Sea in the 20th century and could lead to pollution. According to the DEA permit, pipelaying vessels must use a dynamic positioning system (DPS), which excludes the anchoring risks. Nord Stream 2 AG (NS2AG), the Swiss-based Gazprom subsidiary, has not submitted (as of the beginning of May) nor has DEA received any request to amend the permit, so MRTS could be involved in the project. The Russians plan to use the Akademik Cherskiy vessel owned by one of Gazprom’s subsidiaries and equipped with DPS. After a three-month voyage from Asia where it had been dispatched to the Baltic, it is supposed to be upgraded and then begin work on NS2. This probably will take a few months more, but it remains an open question as to what the real capabilities of the vessel are and the start date. Storms and other complications should also be taken into account. According to the Russian side, NS2 should be completed at the end of 2020 or in the first quarter of 2021.

The Challenges to Pipeline Operations

Gazprom’s concern is that the company will not have full control of the pipeline after it is commissioned. On 23 May 2019, the updated Gas Directive, which now extends Union law to pipelines linking to EU and third countries (so, also to NS2) entered into force. The effect is that such pipelines must function according to EU law: an independent operator must be designated, transparent tariffs must be applied, and access by third parties must be ensured. Gazprom, which has the monopoly on exports by pipeline from Russia, is especially concerned by the latter requirement. It means that access to NS2 should be granted to its domestic competitors, such as Rosneft, which has lobbied for this for years now. If it doesn’t happen, the European Commission might ask the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) to limit Gazprom’s access to NS2’s capacity.

The amendments to the Gas Directive had been stalled mainly by Germany, which, however failed to gather the blocking minority needed at the February 2019 EU Council to halt the changes. After the directive’s transposition to German law, Germany doesn’t have options for further political action. Also, NS2AG’s attempts to legally challenge the Gas Directive have had no effect.

According to the Gas Directive, pipelines completed before the amendments may apply for a derogation, which means an exception from some of the directive’s new rules. Therefore, NS2AG has attempted to change this meaning in the directive by interpreting it in a way that would make NS2 eligible for the derogation The company and some of its supporters try to push forward the idea that the pipeline had been “economically” completed, so, according to this interpretation, the date of “completion” should not be determined by the physical construction of the pipeline but by the fact that the investment decisions on the project had been taken before 23 May 2019. NS2AG representatives have also argued that the requirement of completion before 23 May 2019 should be applied only to the NS2 part in German territorial waters. Following this strategy, NS2AG applied on 10 January 2020 for a derogation to the German regulator, the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA), which will make the decision about a derogation. BNetzA must decide this by 24 May, but, according to a draft decision leaked to media, the regulator will reject NS2AG’s application. The company has already announced it will challenge that decision in German court if issued.

The Gas Directive also allows pipelines completed after 23 May 2019 to be exempted from some of the requirements, but this option is less probable in NS2’s case. The exemption can be granted only once (a derogation may be renewed) for investments that increase the competition and security of supplies, among others. In NS2’s case, there are concerns by some Member States, the EC, and European Parliament that the pipeline does not meet the criteria. Furthermore, in the exemption procedure, the regulators from countries whose gas market might be affected by the decision should be consulted—for NS2, that includes Central and Eastern European states, most likely also Poland. Furthermore, the EC is directly involved in this procedure and can demand additional explanations and expertise. Given these challenges, the Russians might view derogation as the only viable alternative to full implementation of the Gas Directive and push the legal proceedings to challenge the BNetzA decision.

Conclusions

The delays in completing NS2 add to other financial burdens Gazprom has recently suffered, including the lost arbitration cases involving Ukraine’s Naftohaz and Poland’s PGNiG (the Russian company had to pay Naftohaz about $2.9 bn and owes PGNiG $1.5 bn). The company’s financial issues are exacerbated by the dropping gas prices and lower demand stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite these issues, NS2AG and its lobbyists may use the economic crisis as an argument for completing NS2 (and for receiving a derogation for the pipeline and fighting the U.S. sanctions). Reports paid for by the company reiterate the alleged economic benefits Europe will reap from this investment.

Despite the delays and changes in EU law regarding NS2, the threats this project poses, as highlighted by Poland and others, have not changed. The current problems NS2AG is facing are a consequence of the fact that the company started the investment despite earlier EU plans to update the Gas Directive and the possibility the U.S. would introduce sanctions related to Russian aggression. It remains almost certain that no company would take on such risk without political support from the governments of Russia and/or Germany.

Regardless of the progress of the construction of NS2, it is in the EU’s interest to subject it to EU regulations to the fullest extent, as they guarantee transparency. The EC will have to ensure this transparency and possible violations should be red-flagged and sent to the Commission by Poland and others. In case Russia does not ensure third-party access to the pipeline, the ECJ might, upon an EC request, limit Gazprom’s access to it to force Russia to change its rules. The competition between suppliers who may export gas via the NS2, as stipulated in the directive, could mean some economic advantages for them, something the NS2AG refers to in justifying the project, but even in that scenario, it should not weaken Poland and the EU’s push to diversify natural gas supplies, a goal to which NS2 does not contribute.