What are the Prospects for Restricting the Entry of Russians to the EU?

A large number of Russian citizens have tried to enter EU territory since a mobilisation order was announced in their country. Member States, however, could not agree on the criteria for issuing visas. The Baltic states, Poland, and Finland settled on the strictest entry restrictions. Reaching consensus in the EU would be an important political signal to the Russian authorities. A coherent announcement on this issue could also shift the dissatisfaction of Russian society towards the elites responsible for the attack on Ukraine.

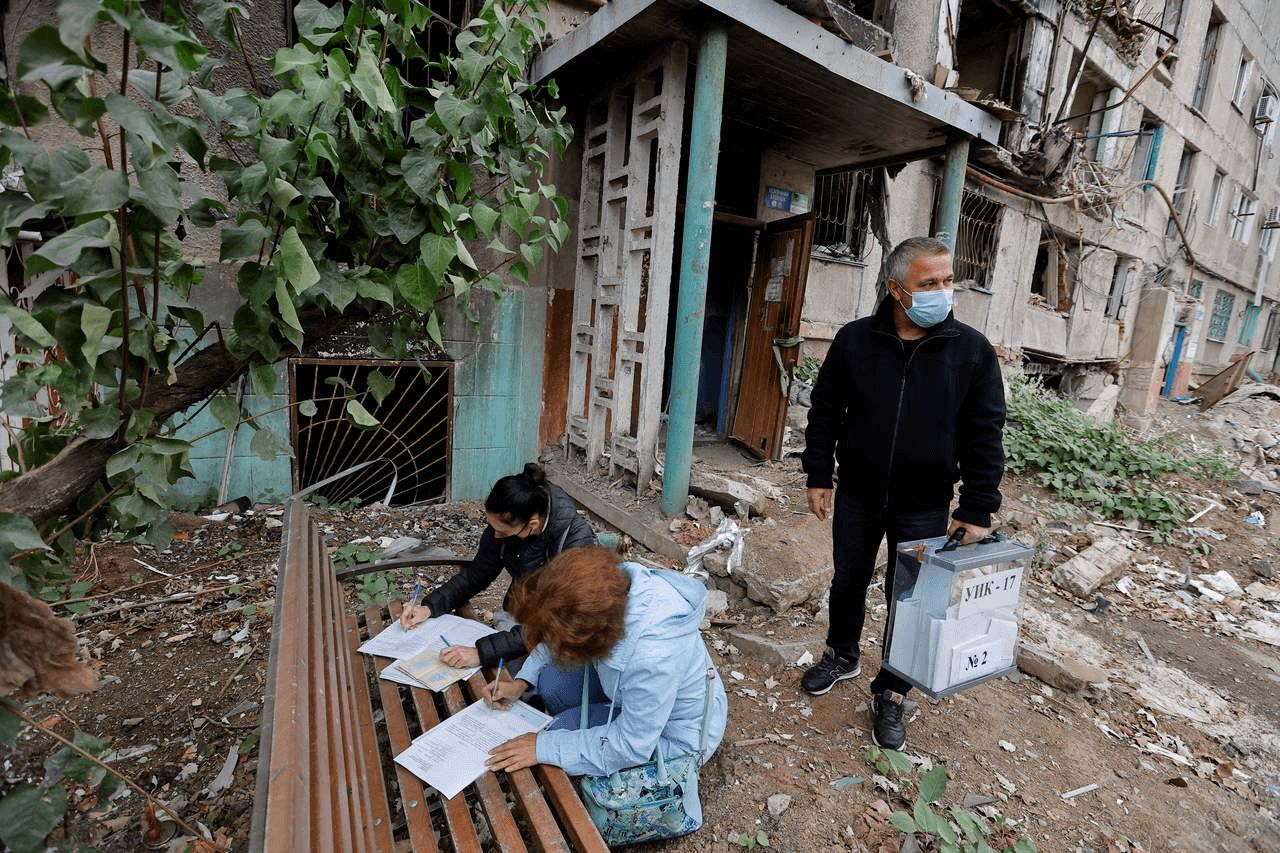

JANIS LAIZANS/ Reuters/ FORUM

JANIS LAIZANS/ Reuters/ FORUM

Russians in the EU

Entry obstacles for Russian citizens were introduced by the EU at the end of February 2022 under the third package of sanctions along with a ban on flights through EU airspace and access to EU airports for Russian carriers. As a consequence, most Russians wishing to enter the EU had to cross land borders of neighbouring countries, mainly Estonia and Finland. Some also exploited other possibilities by flying to Serbia, for example, and then continuing their travel to EU countries such as France and Italy. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, however, did not result in a mass emigration of Russians, and their trips to the EU were mostly of a tourist or business nature.

The EU recorded a significant increase in the number of Russian citizens at its borders after Vladimir Putin’s decree on partial mobilisation of 21 September 2022. According to Frontex data, 66,000 Russians entered the EU in the week the decree was announced, which was 30% more than the previous week. The largest number crossed the border with Finland—30,000 within the first four days of the mobilisation announcement. Most of the Russians who crossed the EU’s borders already had a valid residence permit or visa and some had dual citizenship. Frontex reported that the number of crossings started to decline from 26 September 2022 and the situation at the EU’s borders is stable.

EU Visa Policy

Since the start of Russia’s latest aggression against Ukraine in February, some have called on the EU to introduce visa restrictions on Russian citizens who are not subject to personal sanctions (that list currently has 1,236 names of Russians). The debate sparked anew in the summer when many Russians went on holiday to EU Member States. The controversy over their presence came from the pro-regime attitudes and open hostility of some of the Russian tourists towards refugees from Ukraine. Although during an informal meeting of the Council of the EU in August 2022 foreign ministers discussed the suspension of issuing tourist visas to Russians, no agreement was reached on the issue. It was only agreed that the visa facilitation agreement between the EU and the Russian Federation would be suspended. By the decision of the Council of the EU from 12 September 2022, the entry of Russian citizens for short-term stays that do not exceed 90 days in a 180-day period is carried out according to the general rules of the Community Code on Visas. As a result of this change, the visa fee was raised from €35 to €80, as well as the procedure made more complicated by the obligation to present additional documents, while processing time of the applications was extended. The EU regulations, however, do not apply to long-stay visas, including humanitarian ones, which are based on national regulations. Therefore, it would be even more difficult to reach a common approach on this issue.

New Rules for Entering the EU

At the beginning of September 2022, the European Commission (EC) took two steps in an attempt to increase the coherence of Member States’ actions in relation to visas. First, it published guidelines on general visa issuance in relation to Russian applicants. Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson argued that the possibility of traveling to the EU is not a fundamental right, and Member States—for security reasons—can scrutinise applications, refuse to issue visas, or revoke already issued ones. Thus, applications for tourism purposes, among others, may be processed subsequently in a period extended from 15 to 45 days, and consulates may require documents beyond the standard list to increase the level of control. Decisions are issued individually, which helps to limit discriminatory practices based on the country of origin. Entry to the EU remains possible for the families of EU citizens, journalists, dissidents, human rights defenders, and representatives of civil society. Due to the abrupt increase in the number of Russians fleeing to the EU from mobilisation, the EC updated the guidelines at the end of September, calling on the Member States to strengthen security checks when issuing visas, as well as to tighten border controls.

The EC moreover submitted a proposal on the non-recognition of Russian travel documents issued in occupied foreign regions. The adoption of a decision on this matter would unify the approach of the Member States to Russia’s illegal passportisation process, carried out in the occupied territories, for example, in parts of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts of Ukraine. If the proposal is accepted, passports issued by the occupation authorities would not be considered valid travel documents, and could not be used as a basis for a visa application or crossing an EU border. So far, only a few countries such as Poland follow this approach. Work on the EC’s proposal is ongoing, and the EU’s position has so far been limited to condemning Russia’s illegal annexation of the four Ukrainian oblasts.

Member States’ Positions

Despite the initiatives taken by the EC, a uniform approach to the entry of Russian citizens into the EU has not been developed. The Baltic states and Poland have from the start presented the most principled position, and on 19 September 2022 introduced jointly agreed visa restrictions. They covered Russian citizens traveling for economic, sports, tourist, or cultural purposes at all border crossing points. In accordance with the guidelines of the EC, however, these countries maintained the necessary exceptions and allow entries for humanitarian reasons, among others. Nevertheless, most Russians do not apply for protection in the Member States and prefer to travel to other countries, such as Georgia and Kazakhstan. Although Finland supported the position of the Baltic states and Poland, it postponed taking similar steps, counting on consensus action within the EU. It introduced visa restrictions only more than a week after the announcement of the partial mobilisation in Russia due to the significant increase in border crossings by Russian citizens. Norway, which is the only non-EU member of the Schengen area bordering Russia, is also considering similar actions. So far, the Norwegian authorities have significantly reduced the number of tourist visas issued to Russian citizens, and in September suspended the visa facilitation agreement with this country. Also, several other EU countries, such as Czechia, Slovakia, Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands, have suspended issuing tourist visas to Russians. However, a different position is presented by, for example, Germany and France, which blocked a joint EU decision on this matter in August. Moreover, in September the German Minister of Justice Marco Buschmann stated that Russians fleeing mobilisation are welcome in his country, thus shattering the unity of the EU on this matter.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In view of the reluctance of some Member States, the introduction of further restrictions on the entry of Russian citizens into the EU, including a complete ban on issuing tourist visas, is unlikely for the time being. Such a ban, if introduced, could not be sanctioned by the EU institutions, as decisions on issuing visas are the responsibility of the Member States. The entry restrictions introduced so far result mostly from the determined attitude of the EU members bordering Russia. In this situation, it is worthwhile for Poland to strive to expand the coalition of states supporting further EU entry restrictions. Terminating privileged access by Russians to the EU resulting from the suspension of the visa facilitation agreement did not bring the expected results. First of all, it did not stop the significant increase in the number of Russians trying to cross EU borders after mobilisation was announced. Moreover, it did not channel the dissatisfaction of Russian society towards Vladimir Putin, who is responsible for this decision. However, a coherent announcement on further restrictions on the entry of Russian citizens to the EU could have that potential. The migrants from Russia do not organise anti-war protests in the EU and do not openly oppose Vladimir Putin’s regime, and the underdeveloped civil society and fear of reprisals cannot justify their overly passive attitude. A coordinated approach would also increase the level of security within the Schengen area. It cannot be ruled out that Russians fleeing mobilisation will, for example, present openly pro-regime attitudes or even be hostile to the numerous refugees from Ukraine while in the EU.