U.S. Bombs Islamic State Targets in Somalia

Forces in Puntland, the autonomous region of Somalia, have captured a number of so-called Islamic State mountainous bases on the region’s territory since January with U.S. air support. The Somali branch of IS is now one of the most significant in the organisation’s global structure, attracting volunteers from Africa and the Middle East. The U.S. attack in early February was the first such operation after President Donald Trump took office.

.png) Feisal Omar / Reuters / Forum

Feisal Omar / Reuters / Forum

IS in Somalia

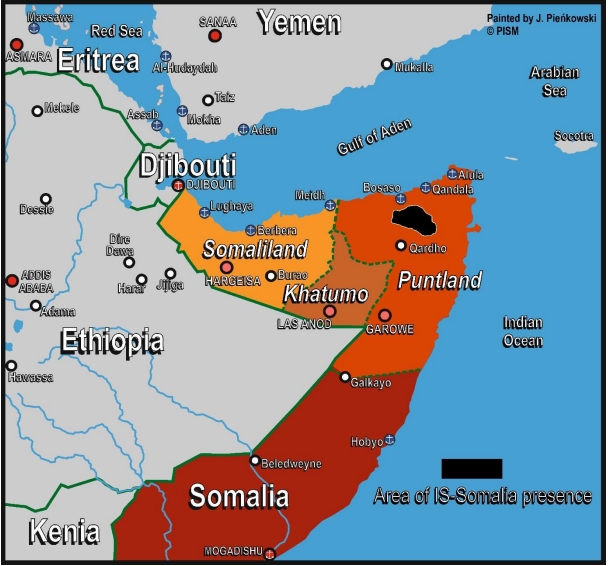

Armed groups appealing to Islamic extremism are firmly entrenched in modern Somalia. They have gained a popular foothold by promoting theocracy as an alternative to clan divisions and the corruption of official authorities in Mogadishu. The strongest of the extremist movements is Al-Shabaab, which has led the fight against the Ethiopian occupation since 2006 to take control of most of the country by 2009. Despite ousting Al-Shabaab forces from the capital Mogadishu with the help of African Union forces between 2010 and 2012, the group still controls much of southern Somalia. It formally became an integral part of Al-Qaeda in 2012, and remains its largest regional cell. IS leader Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi’s 2014 self-declaration in Iraq’s Mosul as caliph of the so-called Islamic State triggered, as in other jihadist organisations around the world, a split among Somali Islamists. In 2015, Al-Shabaab commander Abdulkadir al-Mumin pledged allegiance to the caliph, creating a local IS branch of the (IS-Somalia), of which he became emir. It established itself in the mountains in the north of the country, on the border of the quasi-independent republics of Puntland and Somaliland. For the next few years it was not very active and had only about 200 fighters. IS-Somalia, however, began to play a significant role as a financial hub within IS’s global network, allowing the organisation to finance its affiliates in Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as some operations in Afghanistan. According to the U.S. authorities, terrorist attacks in the U.S. and Europe were planned with its participation.

In the global IS structure, Abdulkadir al-Mumin has grown into one of the most important figures. Last year, the U.S. authorities speculated that he could have even become its new caliph. According to later findings, he serves as the head of the so-called Directorate of Provinces, in other words, the de facto supervisor of the entire, worldwide IS network. In the past year, IS-Somalia has significantly increased its own fighting capacity by attracting volunteers from a number of African countries, such as Tanzania and Ethiopia, and the Middle East, bringing its numbers to around 600-1,000 fighters. It took full control of the Miskaad mountain range located in close proximity to Bosaso, Puntland’s most important port. It was also able to recruit highly qualified specialists, such as Moroccan IT experts.

Puntland Operations

The region’s forces first fought IS-Somalia in 2016 when the Islamists briefly seized the city of Qandala. Since then, they have mainly monitored the group and increased the combat capabilities of their own armed forces, which number around 10,000 troops. In the second half of 2024, alarmed by the IS-Somalia expansion, they turned to international partners for support in a planned offensive against the extremists. They managed to enlist limited help from the U.S. and Moroccan special services, mainly in training and intelligence. At the end of December, they announced readiness for the land-based Operation Hilaac, for which a special group composed of members of the armed forces, police, and coast guard (the latter was set up with the support of the United Arab Emirates, UAE) was drafted in. The authorities also held consultations with clans living in the area of the planned operation to win their support. Since the beginning of January this year, Puntland forces have succeeded in seizing a number of the bases of IS-Somalia, whose fighters were retreating under the pressure. In January, for example, these bases included one that housed a recruiting office, and in early March the likely quarters of the group’s emir and senior leadership, as well as a sniper training centre, were captured. They were located in mountain caves reinforced with concrete structures, where supplies and equipment were gathered. In response to the offensive by Puntland forces, IS-Somalia launched a series of suicide attacks against them using trucks filled with explosives, often led by foreign fighters. This method mimics the actions of its parent organisation in Iraq from the period of its expansion around 2013-14. Having scant air capabilities, the Puntland forces in January announced the addition of their first helicopter to their operations, with airstrikes against IS-Somalia targets carried out by UAE aviation squads.

At the same time, Puntland authorities are trying to publicise the situation, pointing to the global nature of the IS-Somalia threat. Puntland forces, for example, displayed the passports of slain or fugitive fighters found in bases in the Aleelo-Yar region that were destroyed in late March. They belonged to citizens of Saudi Arabia, Germany, Argentina, Tunisia, Morocco, Kenya, Lebanon, Bahrain, and Bangladesh.

US Actions

In early February this year, President Donald Trump authorised the first strikes against IS-Somalia leaders. The move came despite the new administration’s campaign narrative of reducing involvement in foreign conflicts. These actions were, however, a continuation of earlier policies.

Since 2003, the U.S. has carried out airstrikes, mainly using combat drones, against extremists in Somalia. In the case of those affiliated with IS, the last raids in Puntland under the previous U.S. administration took place in June 2024, while last October, the head of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) sounded the alarm about the growing threat from IS-Somalia, indicating that the organisation had doubled its forces in a short period of time. It can be assumed that Trump accepted the list of targets presented to him by the military, selected in connection with Operation Hilaac’s ground, UAE air, and U.S. intelligence activities. They promised high effectiveness at low cost and offered the possibility of politically discounting the operation. After it was carried out, Trump claimed he was succeeding where his predecessor, Joe Biden, had “failed”.

At the same time, Israeli media reported that the U.S. authorities were considering Puntland as one of the places to which Palestinians from Gaza could be resettled. This was met with an inconsistent response from Puntland officials. While Deputy Information Minister Yaquub Abdalle suggested in an interview with The Daily Telegraph that the region would be willing to accept them, his superior, Minister Mohamud Aidid Dirir, categorically ruled it out, indicating the former had shared a private opinion. Regardless of this stance, in the following weeks the U.S. launched a series of further strikes against IS-Somalia targets, coordinated with the advances of Puntland ground forces.

The cooperation with Puntland is also part of the shift in U.S. policy toward Somalia, fostered, for example, by Peter Pham, who is anticipated to become the future Assistant Secretary of State for Africa. He has signalled a desire to end support for the internationally recognised but dysfunctional and foreign aid-dependent authorities in Mogadishu in order to guide policy toward Somalia by the criterion of effectiveness. In addition to cooperation with Puntland, this could even include recognition of Somaliland’s independence.

Conclusions and Outlook

The Somali affiliate of the IS has in a short time grown into one of the most significant parts of its global structure. Its neutralisation is in the mutual interest of Puntland, Somalia, African and Middle Eastern countries, as well as the EU and the U.S. The proximity of the group’s bases to the Gulf of Aden and Yemen increased the risk that it would become another threat to the security of maritime trade routes, in addition to Houthi activities. The course of the campaign so far, with Puntland’s ground forces leading the way, indicates that there is a real chance of defeating, or significantly weakening, IS-Somalia. Even if it leaves the Miskaad mountains and revives elsewhere, the loss of infrastructure it has built up over the years will be impossible to make up for in the short- to medium term.

The active involvement of U.S. forces in the fight against IS-Somalia is the first example of their military involvement in crises in Africa since Trump took power. This could accelerate diplomatic engagement on the continent, as some are hoping, such as members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Success or failure in Puntland will be an important indicator in this regard. It may also play a role in justifying the continuation of some U.S. military missions that have direct benefits, including from the point of view of EU interests, but whose future is uncertain, such as in northeastern Syria. The EU should therefore increase the pressure on IS-Somalia, including by expanding sanctions that facilitate the dismantling of the organisation.