Ethiopia Seeking to Regain Access to the Sea

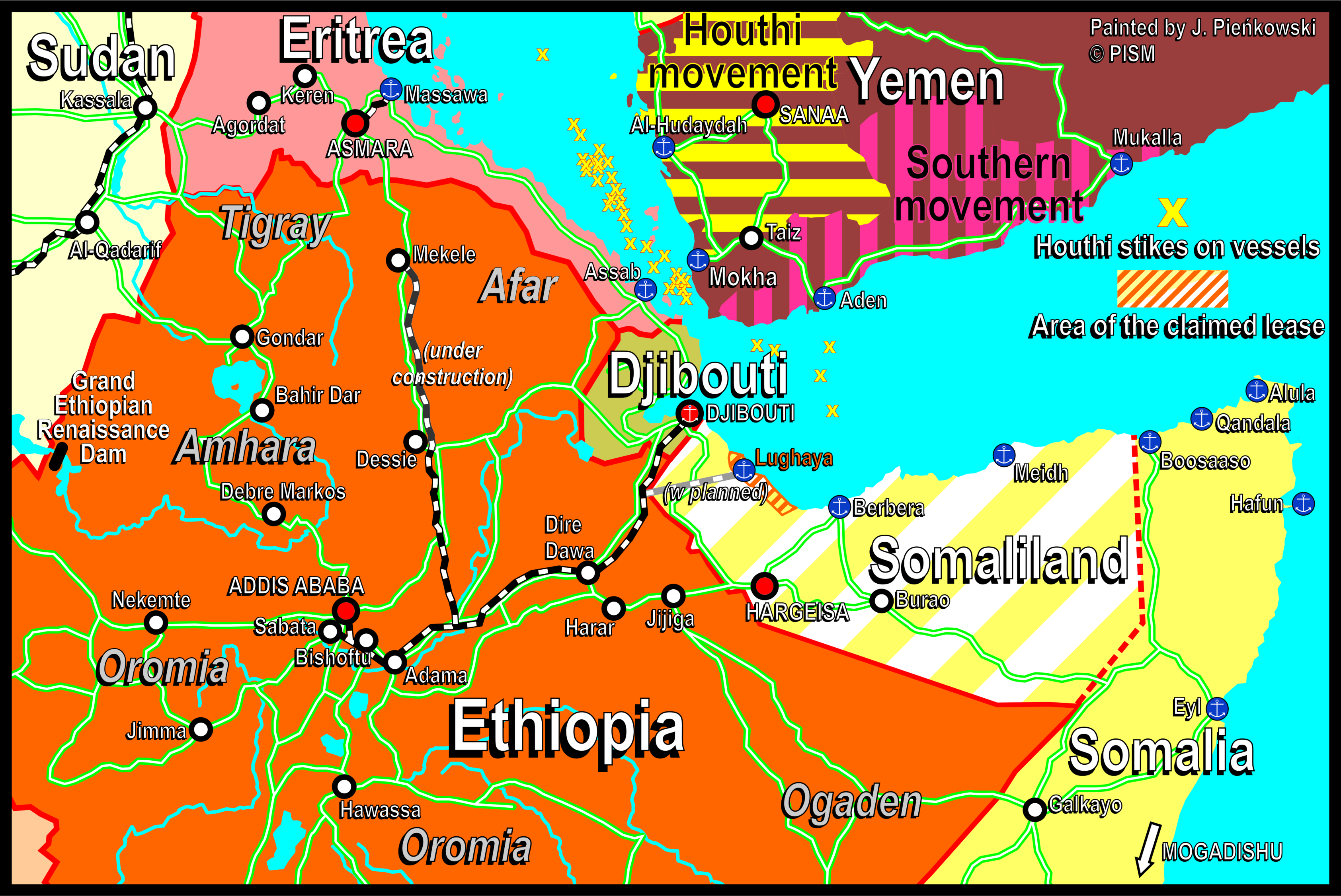

The president of the unrecognised Republic of Somaliland, an integral part of Somalia under international law, has agreed to lease 20 km of coastline to landlocked Ethiopia for a naval base and commercial port. In return, Ethiopia would be the first country in the world to formally recognise Somaliland. The Somali government considers this a hostile act and threatens to take retaliatory measures. The conflict is likely to consolidate the de facto division of Somalia and complicates the security situation around key maritime trade routes.

TIKSA NEGERI / Reuters / Forum

TIKSA NEGERI / Reuters / Forum

On 1 January, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Somaliland President Muse Bihi signed a memorandum of understanding on the lease of part of its territory. Its full content has not been disclosed and the details of the contract are to be finalised by the end of the month. However, the statements of the parties’ representatives indicate that Ethiopia is to lease a section of the coast in the Awdal province in Somaliland, neighbouring the Republic of Djibouti, for 50 years. There, Ethiopia will locate a future navy base, as well as a commercial port, and will build a 90‑km railway line. The Ethiopian authorities also will recognise the independence of Somaliland and give it shares in Ethiopian Airways, the most profitable state-owned enterprise.

Status of Somaliland

In the 19th century, the lands inhabited by Somalis were divided between European colonial powers, comprising Great Britain, Italy, and France, and the Ethiopian Empire. During decolonisation, the former so-called British Somaliland, a protectorate on the lands of the Isaaq clan on the Gulf of Aden, won independence on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland with its capital in Hargeisa. It has been recognised by, among others, the UK, France, China, Ethiopia, and Egypt. Four days later, due to cultural and historical ties, Somaliland united with the so-called Italian Somaliland to form the Republic of Somalia with its capital in Mogadishu within its currently recognised borders. The act of union, which was supposed to define the framework for integration, was never created and the people of Isaaq faced discrimination in the new country. It intensified under the dictatorship of Gen. Siad Barre (1969-1991), as a result of which an armed separatist movement was established in Somaliland. In response to the fall of Barre and the disintegration of the Somali state in 1991, the region unilaterally proclaimed independence. In 2001, in a credible constitutional referendum that served as a plebiscite confirming the de facto independence of this country, this course was supported by 97% of voters (with a turnout of about two-thirds of the eligible inhabitants of Somaliland).

Although many countries maintain actual diplomatic and consular relations with Somaliland (e.g., host missions issuing visas), none have yet recognised its independence. The Somaliland authorities argue that there are more international legal arguments for this than in the case of Eritrea and South Sudan, which were internationally recognised in 1993 and 2011, respectively. There is also a functional argument for Somaliland’s statehood: unlike Somalia, which was plunged into chaos, it remained stable, free from jihadist influence, and created efficient and relatively democratically elected institutions. The Somali central authorities in Mogadishu seek to regain control over the entirety of their internationally recognised territory, so they assume the reintegration of Somaliland.

Ethiopia’s Motivations

Ethiopia, with a population of 130 million and the largest economy in the Horn of Africa, has been landlocked since Eritrea, its former province, gained independence. Although initially able to use its ports, it lost this opportunity with the outbreak of the Ethiopian-Eritrean War (1998-2000). From then on, foreign trade was conducted mainly through the port in the capital of the Republic of Djibouti, connected to Addis Ababa by a railway line built in 2010-2015. Currently, 90-95% of Ethiopia's trade goes through Djibouti, but the conditions are not favourable for it. Transit costs reach $1.5 billion annually, which is about 10% of the Ethiopian budget. The 2018 agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea on the normalisation of relations (for which Prime Minister Ahmed received the Nobel Peace Prize) envisioned the restoration of exports through Eritrean ports. However, relations quickly deteriorated and broke down completely after the agreement between the central authorities of Ethiopia and the Tigrayan TPLF movement (2022), which ended the war in Tigray, and which Eritrea sought to completely destroy.

As a result of growing frustration with these limitations, in October 2023 in a televised address, Ahmed stressed that the Red Sea is Ethiopia’s “natural border” and access to the sea is an existential issue for it. This was partly motivated by Russia’s example and the feeling that forcible border changes could be effective, as well as the hope for nationalist mobilisation in a country mired in an economic and security crisis. Neighbouring countries Djibouti, Somalia, Kenya, and Eritrea found the content and tone of the appeal unacceptable. Somaliland remained the only possible direction for the idea’s implementation.

Regional Implications

The Somali authorities, who in December were conducting what seemed to be breakthrough talks with Somaliland on areas of renewed cooperation, were surprised by the agreement with Ethiopia. They quickly declared it null and void from a legal point of view and concluded that Ethiopia, the historical adversary, was violating Somalia's sovereignty. Therefore, they began to mobilise citizens around anti-Ethiopian sentiments: they inspired rallies in the country condemning Ethiopia and government representatives announced Somalia’s readiness for armed resistance. Islamists also spoke in a similar spirit, both jihadists from the Al Qaeda-linked Al-Shabaab group, as well as those who have joined its authorities in recent years.

Statements recognising Somalia’s legal arguments and calling for de-escalation were issued by, among others, the European Union, Arab League, and the Organisation of the Islamic Conference. The U.S. authorities, despite conducting talks with Somaliland on establishing a military base, expressed a similar tone. The most far-reaching declarations of “unwavering” support for Somalia’s sovereignty were made by the authorities of Egypt, which is in a dispute with Ethiopia over the already completed Grand Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile. Last December, Egypt left the negotiating format with Ethiopia and Sudan on the GERD after 10 years and is more willing than before to actively oppose Ethiopia’s interests. No such condemnation was issued by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which has great influence in Somaliland, Ethiopia, and southern Yemen, and which pursues an assertive policy in the Horn of Africa.

Perspectives

In the face of the Yemeni Houthis’ attacks on ships on the route through the Bab al-Mandab Strait and the Red Sea, the issue of coastal control in this sensitive section is gaining importance. The possible addition of Ethiopia, a country dependent on support from the UAE, to the group of countries influencing navigation security issues weakens Saudi integration activities in the region, especially the Red Sea Council established under Saudi patronage in 2020 with the participation of eight countries in the region, but excluding the UAE and Ethiopia.

Somalia has no way to threaten Ethiopia in a full-scale conflict, as this country is only rebuilding its institutions and independent military capabilities. It is also too involved in the fight against Al-Shabaab extremists, and the U.S. will discourage it from becoming distracted from this goal. However, the government in Mogadishu may demand the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops from its territory, where they are present to support the fight against extremists, and an anti-Ethiopian resistance movement supported by jihadists may develop in Somalia, similar to the one that forced it to withdraw in 2006. The wave of Somali nationalism may also increase centrifugal tendencies in the Ethiopian province of Ogaden, inhabited by Somalis. The withdrawal of troops from Somalia would be painful for Ethiopia, for which this presence (partly under the EU-funded African Union ATMIS mission) is one of its few sources of foreign exchange. It would deepen its already serious financial crisis. Somalia may seek military support from partners by, for example, inviting the Egyptian air force to its territory and acquiring military equipment from Turkey, which cooperates closely with the Somali armed forces and competes with the UAE.

If Ethiopia formally recognises Somaliland, the UAE may be the next country to do so, opening the way to similar declarations by other countries, which would avert the prospect of reuniting the Somali state. This will strengthen the UAE’s position as an independent, influential player in the region and one that can disregard international law and the position of the great powers.

While open conflict between Somalia and Ethiopia is unlikely, it is desirable that the EU actively supports de-escalation. At the same time, however, it should prepare for the possibility of another extension of the mandate of the ATMIS mission in which it is involved.

.jpg)