Trump's Return Challenges the U.S.-Japan Alliance

While Japan remains a key U.S. ally in the Asia-Pacific, it is concerned about many of the new administration’s actions, particularly on the economic front, such as the threat of tariffs. To avoid them, Japan plans to increase imports of American LNG and investment in the United States. In addition to strengthening its alliance with the U.S. and building up its own defence capabilities, Japan will develop security cooperation with partners in the region and beyond, including Poland.

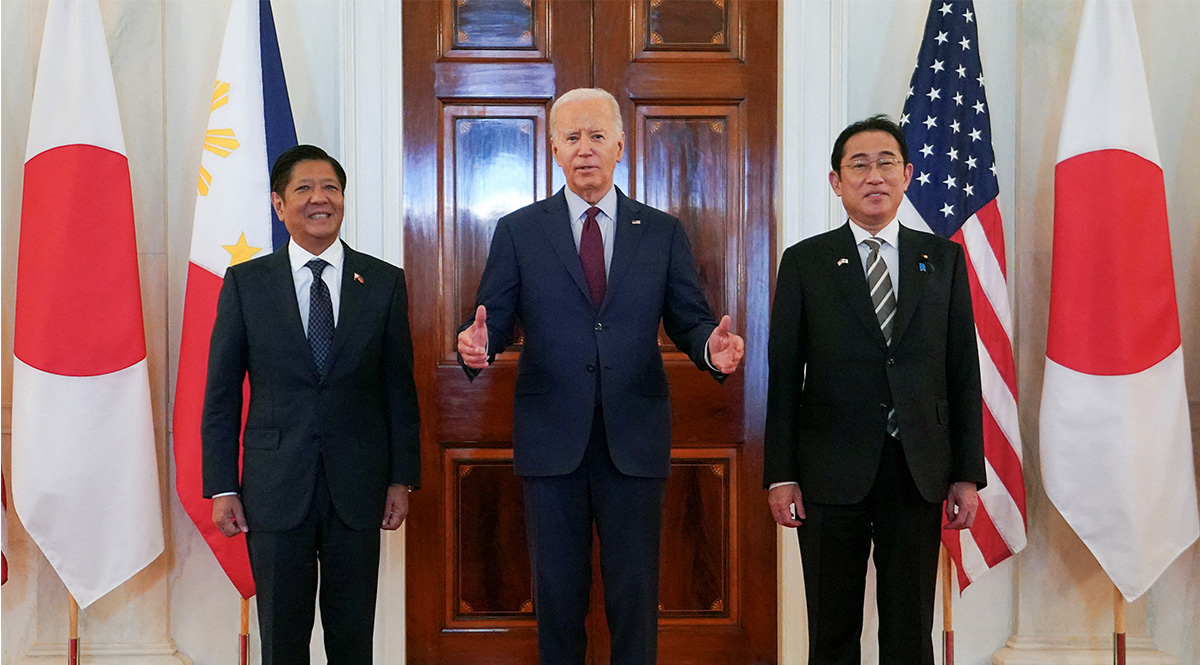

(2).png) Chris Kleponis / Zuma Press / Forum

Chris Kleponis / Zuma Press / Forum

During Donald Trump’s first term in office (2017-2021), Japan had a stable relationship with the United States. This was despite trade disputes, including the imposition of tariffs on Japanese steel and aluminium, and the U.S. president questioning the legitimacy of the alliance between the two countries. The maintenance of good relations was made possible by, among other things, the close personal relationship between then Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and President Trump and by Japan’s non-antagonistic stance towards the U.S. in the economic sphere (it did not use retaliatory tariffs), which allowed for the signing of a trade agreement in 2019. In addition, Japan convinced the United States of the concept of a free and open Indo-Pacific and a return to the Quad formula (cooperation between Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S.), which was initiated in 2007.

Under Joe Biden’s presidency (2021-2025), the two countries deepened security, economic, and technological cooperation. The U.S.-Japan alliance also became the basis for the development of multilateral cooperation in the region, including the U.S.-Japan-South Korea and U.S.-Japan-Philippines formats. Towards the end of Biden’s term, however, a major dispute arose over the U.S. president’s blocking of the $14.9 billion acquisition of U.S. Steel by Japan’s Nippon Steel. The decision was the fulfilment of a Biden campaign promise not to allow a takeover of an American steel company, arguing that it would threaten U.S. national security.

Japan has smoothly established contacts with the new U.S. administration. Foreign Minister Iwaya Takeshi was one of the first heads of diplomacy to meet with Secretary of State Marco Rubio (21 January). And on 7 February, Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru became the second foreign leader after Benjamin Netanyahu to meet Trump in Washington.

Economy

According to U.S. data, U.S. merchandise trade with Japan amounted to $228 billion in 2024, with a deficit of $68 billion on the American side. Only China, Mexico, Vietnam, Ireland, Germany, and Taiwan had larger trade surpluses with the United States. In contrast, the U.S. is Japan’s second-largest trading partner after China and the largest market for Japanese exports (20% of all exports according to Japanese data). Japan has also been the largest foreign investor in the U.S. in terms of capital inflows over the past five years, with cumulative Japanese investment in the United States reaching $783 billion in 2023.

Japan’s biggest concern is the Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs on imports from countries with a trade surplus with the U.S. (including China, Canada, and Mexico) and on selected product categories (including steel and aluminium). The Japanese auto industry, which accounts for 20% of Japan’s total exports with 40% of sales to the U.S. (compared to only about 1.5% for steel and aluminium), is particularly vulnerable to the impacts of tariffs. Many Japanese cars are exported to the U.S. from plants in Canada and Mexico, so tariffs on those countries will also hurt Japan’s economy.

The U.S. is unlikely to participate in multilateral economic agreements, such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) initiated by the Biden administration and supported by Japan. The takeover of U.S. Steel by Nippon Steel remains unresolved. Trump opposes the idea, proposing instead an “investment” that would amount to the Japanese company taking a minority stake in the U.S. company. But Nippon Steel’s management insists on its original intention.

Despite its many problems, the Ishiba government is taking a conciliatory approach to the Trump administration. Unlike China, Canada, the EU, and others, Japan is not announcing retaliatory tariffs in response to possible U.S. restrictions. To obtain exemptions for its companies and avoid further tariffs, Japan is prepared to increase imports of energy resources from the U.S., particularly liquefied natural gas (LNG). Ishiba also announced an increase in Japanese investment in the U.S. worth $1 trillion. This could include the construction of LNG infrastructure in Alaska and the development of artificial intelligence in the U.S. through the Stargate project, a joint venture between Japanese Soft Bank, Oracle, and Open AI.

Security

A statement following the Trump-Ishiba meeting reaffirmed the pillars of the alliance, including U.S. security guarantees to Japan, which applies also to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, claimed both by Japan and China. It also reaffirmed Japan’s commitment to developing its defence capabilities and taking primary responsibility for its own security by 2027. Unlike the Biden-era statements, the document made no reference to the rules-based international order and the war in Ukraine. It was limited to a statement about defending the status quo in the region and the need to counter threats from China. The U.S. and Japan expressed their opposition to Chinese attempts to change the situation in the South and East China Seas and the Taiwan Strait whether by force or coercion, including economic. They intend to continue their existing regional security cooperation with Australia, the Philippines, India, and South Korea. The most problematic cooperation may be with the latter should there be an escalation of historical disputes between Japan and South Korea following possible early presidential elections in that country.

The Trump administration may ask Japan to pay more of the cost of stationing the around 55,000 U.S. troops on its territory. Under the current five-year agreement (2022-2027), Japan pays about $2 billion annually for this, which is about 75% of the cost of stationing the U.S. troops. Statements by Elbridge Colby, nominee for undersecretary of defence in the Trump administration, suggest that the U.S. may also press Japan to increase its defence spending to 3% of GDP. It stood at 1.6% of GDP in 2024 and is set to rise to 2% by 2027. To persuade the U.S. ally to change, Trump will downplay the importance of the alliance and question the legitimacy of security guarantees to Japan.

Japan’s concerns may be elevated by the Trump administration’s moves to improve relations with Russia and its decision to suspend military aid to Ukraine. This contrasts with Japan’s position as a G7 member providing political, humanitarian, and economic support and non-lethal arms supplies to Ukraine (the value of Japanese aid since the full-scale invasion has been $12 billion). A possible return of the U.S. to negotiations with North Korea could also be problematic for Japan, especially if it leads to the abandonment of efforts to denuclearise the North, which is a priority for Japan.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Japan remains a key ally of the U.S. in its strategy to contain China. It intends to develop military capabilities and become more involved in regional security. This may manifest itself in further allied coordination on regional tensions, including in the Taiwan Strait. Details of such cooperation could be worked out at the “2+2” meeting announced by Trump and Ishiba involving the heads of the foreign and defence ministries of both countries.

Ishiba’s meeting with Trump was a success for Japan, as it received confirmation of U.S. security guarantees and so far has avoided tariffs (it is seeking an exemption from the steel and aluminium tariffs). In order to maintain favour with the Trump administration, which is necessary given the importance of the U.S. to Japan’s security and economy, the Japanese government will avoid becoming involved in issues that could raise U.S. concerns. An example of this attitude was Japan’s decision not to sign a statement in support of the International Criminal Court in response to U.S. sanctions on it and Japan’s reluctance to comment on the dispute between Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

As a beneficiary of the rules-based international order, Japan will seek to preserve it. To this end, Japan’s aid agencies may partially fill the gaps left by the U.S. withholding of development assistance, including in Ukraine. Japan will also deepen cooperation with EU and NATO partners, including Poland. This is evidenced by the Action Plan for the Implementation of the Strategic Partnership for 2025-2029, signed on 28 February during the visit of Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski to Tokyo. In addition to economic issues, Polish-Japanese cooperation in the security dimension, such as joint military exercises (for example, paratroopers), combating cyber and hybrid threats, and the political dimension, such as emphasising the support for Ukraine and respect for international law, will gain in importance.

_Easy-Resize.com.jpg)