The Revolution in Bangladesh Raises the Prospect of Renewed Democracy

On 5 August, a social revolution forced Bangladesh’s long-serving Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to step down and leave the country. The massive anti-government protests were caused by a combination of the authoritarian rule and increasingly difficult post-pandemic economic situation. A transitional government led by Nobel laureate Mohammad Yunus will be tasked with stabilising the country and preparing for free and fair parliamentary elections. It is in the West’s interest to strengthen democracy in Bangladesh. Poland can use this moment of democratic transition to intensify bilateral cooperation.

(1).png) Mohammad Ponir Hossain / Reuters / Forum

Mohammad Ponir Hossain / Reuters / Forum

Reasons for the Revolution

Prime Minister Hasina, leader of the People’s League (Awami League, AL) has ruled Bangladesh since winning the 2008 elections. By providing political stability and security, she created a good environment for rapid economic growth, exceeding 6% of GDP per annum between 2008 and 2023. During this time, nominal GDP per inhabitant quadrupled, from $600 in 2008 to $2,529 in 2023, and Bangladesh was expected to graduate from one of the least-developed to among the low-income countries in 2026. However, the COVID-19 pandemic slowed the country’s pace of development and the rebound afterwards resulted in higher inflation (to 7% in 2023), increased cost of living, and rising unemployment among the young population (15.7% of people under 24 years of age were unemployed in 2023, compared to 5.1% in the total population).

Poor economic prospects for the young population (half of the 174 million residents is under the age of 26) compounded the frustration from life under increasingly authoritarian rule. For years, human rights organisations have pointed to growing restrictions on freedom of expression and criticism of the authorities, extrajudicial killings, “disappearances”, and torture of political opponents, activists, and NGO members. In 2011, the provision in the constitution that a transitional government had to be established to conduct free and fair elections was removed. The authorities then asserted their influence over how the vote was prepared and exercised. As a result, all elections in recent years have been accused of manipulation and rigging, and the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) boycotted the 2014 and 2024 elections. A number of opposition leaders, including BNP chief Khalida Zia, have been jailed. Although the last elections in 2024 were decisively won by the AL (222 out of 300 seats) and it managed to quell post-election protests, the low voter turnout (40% compared to 80% in 2018) indicated growing public frustration.

The outbreak of anti-government protests was triggered by a Supreme Court decision on 5 June this year reinstating quotas suspended by the AL government in 2018 reserving public jobs for particular social groups, including 30% for descendants of the heroes of Bangladesh’s 1971 independence war. This mass protests that started on 1 July began with students who, faced with a shortage of attractive jobs in the private sector, saw further restrictions on access to public positions as another step towards state capture by AL supporters. However, it was only the attempted brutal crackdown of the peaceful protests and the deaths of demonstrators (around 450 in total) that escalated and changed the nature of the protests from economic to political, resulting in the call for Hasina to step down. Faced with the announcement of a “march on Dhaka” on 4 August and the risk of further bloodshed, the army refused to protect the prime minister but allowed for her departure for India on 5 August and subsequent resignation. As early as 8 August, the military handed over power to Mohammad Yunus as head of the transitional government (formally serving as Chief Advisor to the government).

Challenges for the Transitional Government

The appointment of Yunus, winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize and Bangladesh’s most high-profile citizen in the world, was the army’s nod to the demands of the student protesters and a promise that democratic standards would be restored. As a social activist and promoter of micro-financing, Yunus has for years called for an end to the debilitating conflict between the two main parties and an overhaul of the country’s political and economic system. He invited leaders of the student movement, former activists and government officials, and human rights defenders to join his government. The authorities released detained demonstrators and political prisoners from prison.

The primary task for the transitional authorities was to restore the rule of law, rebuild confidence in the state, and hold those responsible for the bloodshed to account. The resignation of the Hasina government was followed by a period of lawlessness—there were acts of revenge against supporters of the previous regime, attacks on places of worship and members of religious minorities, especially Hindus. The legalisation of Islamic parties and the release from prison of their leaders, some of whom were accused of terrorist activities, raise the risk of wider Islamic extremism. The weekslong protests and state of emergency have also curtailed economic activity, which could add to the country’s economic problems. However, the Yunus government’s most important goal is to reform key institutions, including the electoral commission, judiciary, and police, and perhaps even amend the constitution to prepare for free and democratic elections.

The interim authorities will run the country until the vote, but it has not been specified how long this may last. According to the repealed provisions of the constitution, such a mechanism was supposed to operate for up to 90 days, but in practice it has sometimes lasted more than a year (e.g., in 2007-08). The opposition BNP, which is most likely to win, and religious parties such as the Jamiat-e-Islami are interested in holding elections quickly. However, Yunus may want to extend the transition period to prepare the election and give the student movement more time to form its own party. It is not yet certain whether AL will be allowed to stand in the elections or how its supporters will react in case of defeat. Unnecessarily prolonging the transition period could, however, lead to renewed tensions and violence.

International Significance

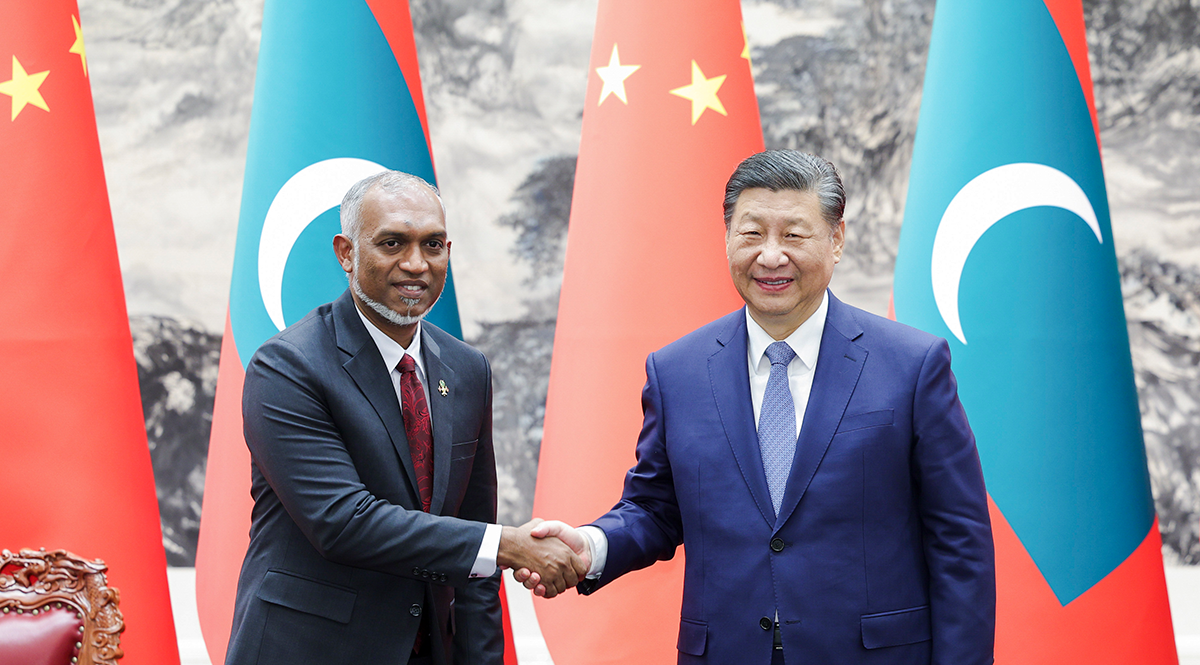

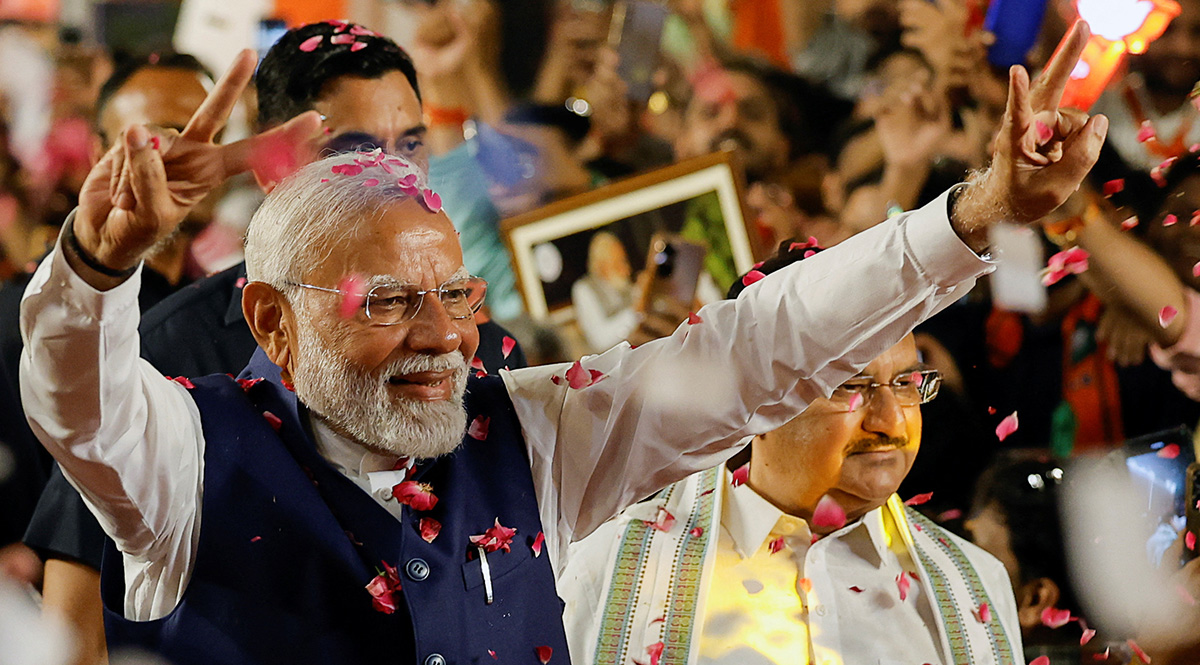

In the short term, the events in Bangladesh are most detrimental to India, which has lost its closest partner in the region. The strong support for Sheikh Hasina showed over the years and sheltering her will put a strain on India-Bangladesh relations. China, which has become Bangladesh’s largest trading partner in recent years, could benefit. Prime Minister Hasina visited Beijing as recently as 9 July this year, where she signed 21 agreements. Bangladesh can also expand security cooperation with China in the Indo-Pacific, giving it greater access to ports and military installations. However, the transitional government’s pro-democracy stance will make it seek rapprochement with the West rather than with China.

The U.S. and the EU, which had an increasingly tense relationship with Hasina’s government, have welcomed her downfall and assure Bangladesh of their support for a democratic transition. The EU, which receives almost half of Bangladesh’s exports, has a particular role to play. The prolongation of trade preferences by the EU (EBA), made easier in the face of receding human rights concerns, would be an important support for the Bangladeshi economy. The EU and the U.S. can also facilitate the transition by, among other things, helping to renegotiate Bangladesh’s foreign debt repayments and providing technical assistance to reform democratic institutions, increase media independence and develop civil society.

Conclusions. Bangladesh, once presented by international institutions as a model for fighting poverty, also has the chance to become a model for fighting authoritarianism and rebuilding democracy. The success of this process will depend on the restraint of the victors, the political talent of Yunus, the economic situation, the support of other democracies, and, ultimately, the calculations of the army as it oversees the whole process. The progressive attitude of Yunus, who enjoys the trust of the protesters and credibility abroad, gives hope that Bangladesh can successfully strengthen its democratic system and build the foundations of a more just and free society. However, it is worth remembering that similar popular revolutions against dictatorial rule in Arab countries ultimately brought neither democracy nor development there. The direction of foreign policy will be decided by the government that emerges after the elections, but at present it is difficult to predict its composition.

The West should comprehensively support the political and economic transition process in Bangladesh. This will be important not only to curb Chinese influence, stabilise the Indo-Pacific, and reduce the international terrorist threat but also to strengthen democracy worldwide. Supporting the interim government’s effort to hold fair elections without unnecessarily protracting the transition period should be a priority. The deployment of an EU election observation mission will be an important element in enhancing the credibility of the vote and its results. Poland, which has increasingly strong economic relations with Bangladesh (e.g., through investments by Polish companies), can use this period to strengthen political relations and offer support in the transition. The reopening of the Polish embassy in Dhaka, closed in 2005, would be helpful in this regard.