India's Voters Give Narendra Modi a Third Term

The parliamentary elections in India, which ended on 1 June , were won by the coalition headed by the Indian People’s Party (BJP). Although its leader Narendra Modi will be sworn in as prime minister on 9 June for the third time in a row, his mandate is weaker than after the 2019 elections, and India will face a less stable coalition government. This means greater difficulties than in the previous term in introducing serious reforms and possibly a less active role for India in international politics.

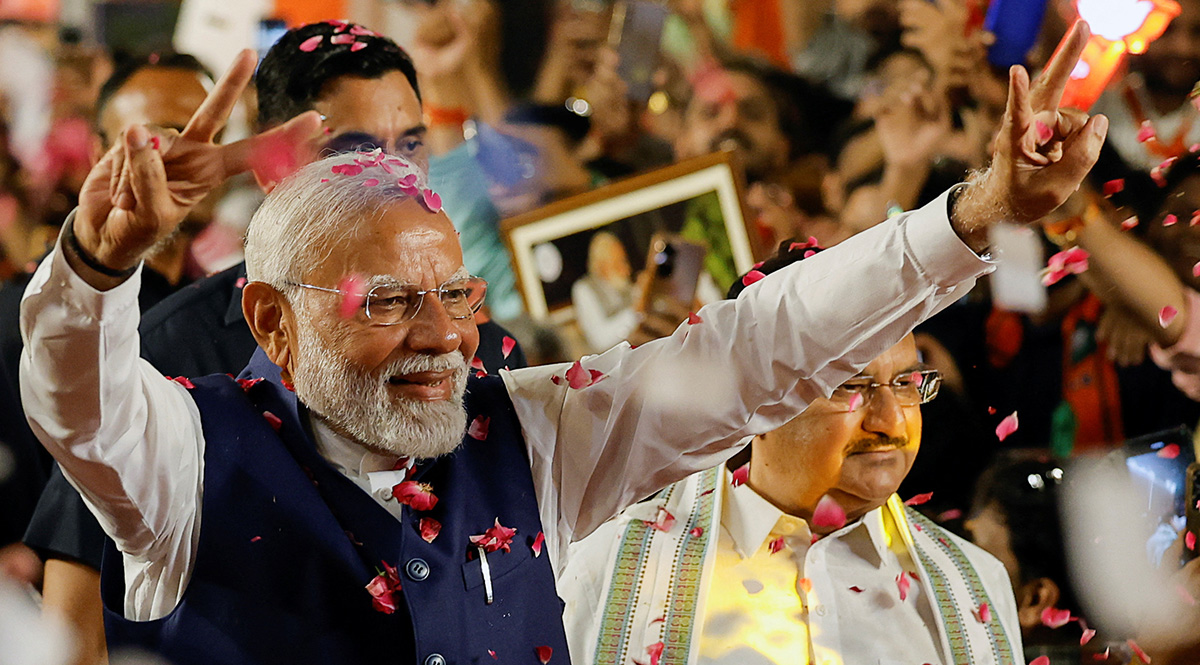

Adnan Abidi / Reuters / Forum

Adnan Abidi / Reuters / Forum

What were the election results?

The Indian general elections were held in seven phases between 19 April and 1 June, with the results announced on 4 June. Of the 969 million eligible to cast a ballot, 642 million voted, making the turnout 66.3%. The ruling party, the BJP, won the most seats—240—in the 543-seat parliament, while the coalition formed by it and allied parties, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), won a total of 293 seats. This is much worse than in 2019 when the BJP won 303 seats, and the entire NDA 353, and it was also below the goals set by the BJP for 400 seats for the NDA, and lower than the exit poll forecast on 1 June. The opposition I.N.D.I.A bloc obtained 233 seats, including 99 for the Indian National Congress (INC), significantly improving its standing from five years ago when it won 54 seats. Despite the weaker results, the BJP and its partners have enough seats in parliament (272 required) to form a government headed by Modi for a third time in a row. This makes Modi the first Indian politician to record such an achievement since 1962.

What caused the decline in support for the BJP?

The BJP campaigned on slogans of a “Modi guarantee” of the continuation of rapid economic growth, strengthening India’s international position, and emphasising the country’s Hindu identity. Despite this, the party lost support in the largest states of Uttar Pradesh (it won 33 seats compared to 62 in the 2019 elections), Maharashtra (from 23 to 9), and West Bengal (from 18 to 12), which resulted in its worse result on a national scale. This was due to growing anti-incumbency sentiment after 10 years of BJP rule (the party had previously also won the 2014 elections) and disappointment with the lack of improvement in the individual life situation of many voters. This applies especially to young people, among whom unemployment reaches 20%, farmers, whose protests in recent months have been ignored by the government, and poorer people who have not benefited from the country’s rapid economic growth. The use of religious rhetoric did not mobilise enough Hindus, but it increased the fears of the Muslim minority (constituting 15% of India’s population), who overwhelmingly voted for I.N.D.I.A. The BJP was harmed not only by the policies of recent years but also by the rhetoric used during the campaign, which increased the religious and ideological polarisation of society. The opposition, which made defending the Indian constitution and democracy and improving the fate of the poorest and minorities one of its main campaign slogans, mobilised voters in key states, and the common bloc prevented individual parties from stealing votes from each other.

What does the election result mean for India’s internal situation?

The BJP’s weaker result than five years ago means a return to coalition governments in India. It strengthens the opposition to Prime Minister Modi within his own BJP formation and the socio-ideological base in the form of the nationalist organisation National Volunteer Corps (RSS). It also increases the role of coalition partners, including regional leaders such as Nitish Kumar, prime minister of the state government in Bihar (his Janata Dal party won 12 seats), or Chandra Babu Naidu, prime minister of the state government in Andhra Pradesh (his Telugu Desam Party won 16 seats). This exposes the future government to the risk of smaller parties withdrawing support and imposing their agenda. Hence, the coalition government may be less stable and less willing to undertake difficult but necessary economic reforms (e.g., agricultural reforms, labour law), which may slow down the modernisation of the country. The lack of a majority necessary to reform the constitution also eliminates the risk of changing the political system and the secular and pluralistic character of India. The good result for the INC will increase the monitoring role of the opposition in parliament, which will block changes that could limit democratic freedoms and marginalise minorities. This averts the risk of India sliding towards authoritarian rule and a Hindu majoritarian state.

What is the international significance of the elections?

The elections confirmed the vitality and efficiency of democracy in India, sending a positive signal to the world, while the quality of democracy on a global scale is regularly deteriorating and authoritarian regimes are strengthening. Modi’s return as prime minister, even with a weaker mandate and stripped of the aura of an invincible strongman, makes him one of the longest-serving leaders of the G20 member states and strengthens India’s position in international affairs as vibrant democracy. At the same time, the warning sent by the voters may encourage the new government to focus more on internal economic challenges, which can reduce its activity in the international arena. One should expect a continuation of the main directions and goals in India’s foreign policy, that is, maintaining strategic autonomy and good relations with all powers, striving to strengthen its major power status, and aiming to become the third-largest economy in the world before the next elections in 2029. The new coalition government will strive to represent the interests of the Global South and cooperate with the West in reforming international institutions. The tough attitude towards China and friendly relations with Russia will continue.

What are the prospects for cooperation with the EU and the United States?

The election result should reduce criticism of the state of Indian democracy in Western media and limit the negative impact of tensions over democratic standards in relations with the EU and the U.S. India, which must quickly respond to the development aspirations of its citizens (including in terms of job creation, income growth, quality of infrastructure), will strive even harder for Western investments, technologies, and opening of markets. This may increase the readiness of the Indian authorities to improve the operating conditions of foreign companies, which will facilitate intensified talks on free trade and investment agreements, including with the EU or the United Kingdom. Despite maintaining a neutral position towards the war in Ukraine, India’s rapprochement with the U.S. and Europe will continue in matters of security and defence (e.g., replacing Russian weapons in the Indian military with those supplied by Western partners), connectivity (the project of the Europe-Middle East-India economic corridor, IMEC), and the energy transformation. The end of the electoral period in India, and soon also in the European Union, opens the way to the organisation of an EU-India summit after a break of several years (the last one took place in 2021), during which a new multi-annual cooperation plan may be adopted. It also means a chance for Poland to intensify cooperation with the government of Prime Minister Modi, who has not visited Poland during his frequent visits to Europe.