Now is the Time to Strengthen Polish-Indian Relations

India’s rise as a global power has been confirmed in recent years. While the U.S., the EU, and its Western European Member States have taken steps to strengthen cooperation with India, Polish-Indian relations have not advanced much. This year, when the countries celebrate the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between them, could be a good opportunity to intensify cooperation and political dialogue at the highest level. To be successful, Polish policy towards India will require treating it as a major power and a key global partner, along with preparing an attractive offer of cooperation and committing more resources to bilateral relations.

ADNAN ABIDI / Reuters / Forum

ADNAN ABIDI / Reuters / Forum

The G20 presidency and the crowning leaders’ summit in New Delhi in September 2023 were diplomatic successes for India and confirmed its growing international role.[1] The Indian economy is growing dynamically—as of 2022, it is already the fifth largest in the world, and according to the IMF, GDP growth in 2023 was expected to be 6.3%, surpassing China’s growth (5%). Before 2028, India could become the third-largest economy, behind only the U.S. and China. The successful Chandraayan-3 mission, which landed a probe on the moon last August, also confirmed India’s position as a space and technology power.

India’s growing status is accompanied by a trend of closer engagement with the West, which has not suffered despite the country’s neutral stance towards Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.[2] In recent years, India has strengthened cooperation with the U.S. in many areas, be they political, economic, technological, or security. It has become a key partner for the United States in its strategy to balance China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific.[3] Under Narendra Modi, the most pro-European prime minister in history, the Indian government has strengthened its strategic partnership with the European Union and elevated relations with more EU countries to that level (Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark and Greece). In January 2024, Czechia became the first country in Central Europe to establish a strategic partnership with India.

Meanwhile, Polish-Indian relations have not changed significantly over the past decade. The countries have failed to raise the profile of bilateral relations, and differences over approaches to the war in Ukraine have further complicated cooperation. The low intensity of political contacts has been accompanied by limited progress in economic and cultural cooperation.

A Lost Decade?

Polish-Indian relations can be described as correct and friendly, but low intensity and of little importance to both sides. This is indicated by the political dialogue held in recent years, which has been irregular and at a low level.

The last top-level visit to India was made by Donald Tusk in his first premiership in September 2010. A visit to India by the Polish president, which the Polish side has been seeking since at least 2014, has not yet materialised.

The Indian authorities have shown even less commitment. Despite Prime Minister Modi’s increased interest in Europe, Poland was overlooked during his numerous visits to the continent. The last Indian prime minister to travel to Poland was 45 years ago, namely Morarji Desai in June 1979.

Polish foreign ministers have rarely visited India (Radosław Sikorski in 2011 and 2014, Zbigniew Rau in 2022). In recent years, there has been only one visit (the first in 32 years) by India’s foreign minister to Poland—S. Jaishankar came to Warsaw in August 2019. More frequent meetings of deputy ministers, visits by deputy prime ministers, and by Indian Vice President Hamid Ansari in 2016 were of symbolic value and generated neither political change nor public interest in bilateral relations.

Minister Jaishankar’s visit to Poland in 2019, when he conveyed an invitation to the Polish president to visit New Delhi, offered a chance to revive political cooperation. These plans were put on hold by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. The launch of full-scale Russian aggression against Ukraine in February 2022, on the other hand, revealed serious political differences between India and Poland and fostered distrust of closer cooperation. Although it did not cause tensions at the official level, Polish diplomats admitted that India’s position in a situation that “from our point of view seems obvious, poses a challenge to Polish foreign policy”.[4]

Contacts through multilateral forums, whether subregional (e.g., within the Visegrad Group or the Three Seas Initiative), regional (in the EU and ASEM), or global (e.g., UN), have not been utilised to intensify the bilateral dialogue. Poland has not been involved in shaping EU relations with India. It did not use the favourable circumstance of Poles holding important positions in EU institutions to strengthen its position vis-à-vis India; notably, there was Tusk, who was president of the European Council in 2014-2019, and Tomasz Kozłowski, the EU ambassador to India, who also coordinates the work of all Member States, in 2015-2019. Despite this, Poland did not play a role in the formation of EU India policy and was unable to benefit from the intensification of EU-India cooperation that began with a summit of the two in Brussels in March 2016.

At the same time, the last decade witnessed several important decisions that have prepared the ground for closer cooperation in the future.[5] These include, in particular, the establishment of the Polish Institute in New Delhi in 2012 and the opening of a foreign trade office of the Polish Investment and Trade Agency (PAIH) in Mumbai in 2018. An important step was the launch by LOT of direct flights between Warsaw and New Delhi in September 2019 (suspended in March 2020 due to COVID-19 and resumed in March 2022) and Warsaw-Mumbai in May 2022. This has also made Poland a more attractive place for Indians to study, work, and travel. The number of Indian students at Polish universities has increased almost tenfold, from 263 in the 2010/2011 academic year to 2,449 in 2021/2022,[6] and the number of Indian citizens legally living in Poland has increased from just over 1,300 in 2010 to more than 18,000 in December 2023.[7]

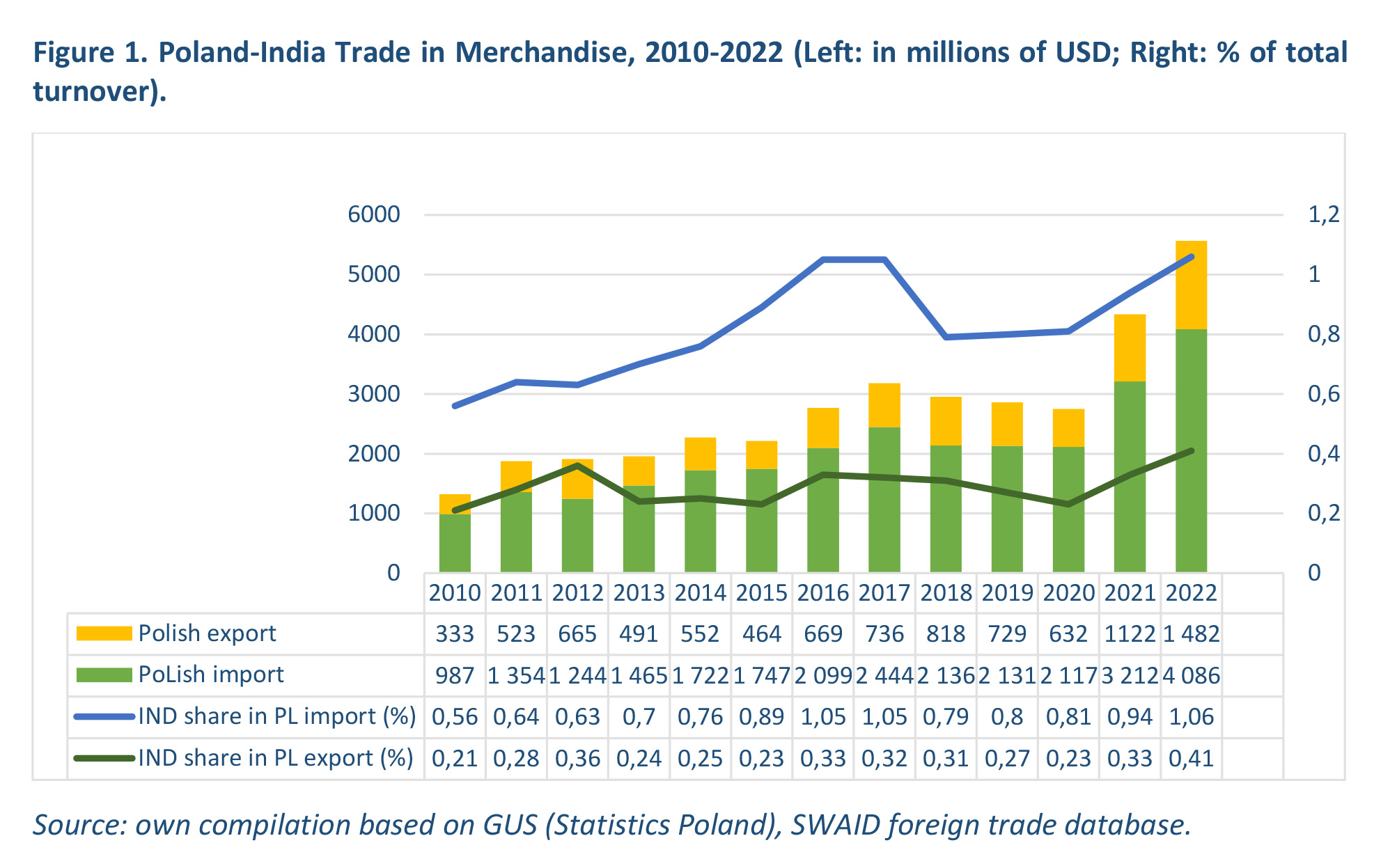

Despite weak political cooperation, economic relations are better developed. Between 2010 and 2022, the value of trade in goods increased nearly fivefold, from $1.32 billion to $5.56 billion.[8] The largest increase was in 2022 as a result of the rebound after the pandemic. However, the increase in trade was mainly the result of rising Polish imports from India. This affects the widening trade deficit in India’s favour, from $650 million in 2010 to $2.6 billion in 2022.

Despite the increase in the value of trade, the mutual importance of the two countries as economic partners has increased only slightly and remains below its potential. For Poland, India is only the 36th market for goods and accounts for 0.41% of exports. It is also the 24th import partner at just 1.07% of imports. However, the importance of investment cooperation is growing. Indian companies are particularly active in Poland, investing in a range of sectors, from IT and services, to biotechnology, to factories (e.g., electronics and packaging).[9]

Three Main Challenges

In the case of Poland, three primary factors can be identified as having a hampering effect on the development of cooperation with India: underestimation of India’s growing international role; lack of an attractive cooperation offer; and, underinvestment in the relationship.

The key problem is the prevailing outdated perception of the political world map in which India as a partner occupies a distant place. It is often still seen as a poor and backwards, developing country. Other mental associations present in Poland are of India as an “exotic and mystical” country, “the world’s largest democracy”, and “like-minded” partner. As a result, Poland has underestimated the growth of India’s power in the international arena and its importance to the West. This has resulted in a lack of understanding of India’s stature and treating it as an equal actor at best rather than a new major power whose attention should be sought. Unlike in the U.S. and Western Europe, in Poland the outdated perceptions of India result in little interest in the country in media, as well as among the political and business elites.

The lack of understanding of India’s changing position is related, on the one hand, to the Eurocentric approach and vision of the world prevalent in Poland and, on the other hand, stems from the complex and contradictory nature of contemporary India, for it functions in many dimensions—it is simultaneously an emerging power and a developing country. It has huge aspirations, but even greater needs. Hence, it is a mistake to adopt the approach that prevails in relations with industrialised countries from Asia, such as Japan or South Korea of treating India as a source of investment and technology. Rather, India expects to be recognised as a world power while it is helped to overcome development challenges.

Traditionally, speeches by foreign ministers on the assumptions and directions of Poland’s foreign policy have not devoted much space to India, and the Foreign Policy Strategy 2017-2022 completely ignored it. Only in the foreign minister’s exposé of 2023 did a top official speak longer about India, but still without indicating specific goals for relations with the country.[10] Further, underestimation of India’s importance is evidenced by the vacancy in the post of Poland’s ambassador to New Delhi since March 2023, that is, during India’s presidency of the G20 when the Indian capital became the diplomatic centre of international affairs.

The failure to understand India’s role and potential has resulted in two negative effects. First, it has made it difficult to prepare an attractive cooperation offer for it. Second, the additional financial, personnel, and political resources necessary to improve Poland’s visibility and strengthen engagement with such a large and diverse country have not been allocated.

Repeated proposals by Polish diplomats and experts since at least 2010 to elevate relations to a “strategic partnership”[11] were regularly rejected by their Indian partners, who pointed to the lack of “content” in relations at this level and as at a “premature” stage of cooperation.[12] Indian experts stressed that, as a first step, it is necessary to “intensify daily cooperation at the basic level” to prepare the ground for a strategic partnership.[13] They argued that in the face of growing interest in India and constraints on diplomatic resources, the Indian prime minister is engaging in a relationship from which he can expect concrete benefits that respond to his country’s challenges in the economic or security spheres.

Meanwhile, in the 21st century, with the restructuring of the Polish defence industry, defence cooperation, traditionally a strategic area of Polish-Indian relations, has lost importance. Cooperation in mining or energy, promoted over the years, has not yielded significant results. Poland, unlike Western European countries, has not made a new offer to support Prime Minister Modi’s modernisation programmes or flagship initiatives implemented since 2014.[14] Also, unlike smaller countries in Central Europe, such as Hungary, Poland has not decided to propose a special scholarship programme or a joint technology fund that could interest the Indian side and develop people-to-people cooperation.

Preparing an offer for India is not an easy task, which is largely due to objective constraints. Poland does not have the strategic resources that India values and seeks, such as energy resources, nuclear fuel, rare earth metals, advanced weaponry, or green technologies. Indeed, Poland and India are often competitors, for example in attracting foreign investment or improving their positions in global value chains.

The offer also is further limited by the resources available for diplomatic cooperation with India. The Polish embassy in New Delhi must contend with a country the size of a continent and with a population of more than 1.4 billion. It has only a dozen employees, far fewer than Poland’s staff in China. The embassy building in the prestigious part of New Delhi stands partly empty today. Personnel and financial constraints have also prevented the Polish Institute and the PAIH office from being more active, which could have provided better promotion of knowledge about Poland and Polish products, thus facilitating the entry of Polish businesses to the Indian market. Export support programmes (e.g., GoIndia) were long underinvested in and eventually abandoned. Austerity thwarted plans to establish additional consulates in various parts of India and forced reliance on visa outsourcing. There was a lack of resources to support diplomacy and business through tied loans, small development assistance grants or an expanded scholarship programme. Relationships lacking increased resources and political will could not develop.

The Shape of a Possible Offer

To strengthen cooperation with India, Poland should above all prepare an attractive offer that could include a proposal to intensify cooperation in many areas—political, security, economic, and people-to-people.

The first step to strengthening bilateral relations should be the intensification of political dialogue, including the realisation of long-postponed top-level visits. The fact that 2024 marks the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between India and Poland provides a convenient opportunity to organise such meetings. The possible visit of the Polish president to India in 2024 should pave the way for the visit of the Indian prime minister to Poland in the following months. It should also be an opportunity to present ambitious plans for cooperation and the adoption of concrete initiatives and agreements to indicate a willingness to elevate bilateral relations to the level of a strategic partnership.

To show itself as an important partner, Poland should skilfully employ regional and global instruments. Its presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2025 is important in this regard, especially since the negotiations of the EU-India free trade agreement may then be in a decisive phase. It may also be helpful to take advantage of Poland’s chairmanship of the Visegrad Group from July 2024 to the end of June 2025, as well as other regional projects in Central Europe that strengthen Poland’s position as a leader in this part of the EU. At the global level, part of the political offer could be unequivocal support for India’s aspirations for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, emphasising condemnation of terrorism in all forms, or joining India-led multilateral initiatives such as the International Solar Alliance (ISA) or the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI). India will also watch the evolution of Poland’s and the EU’s overall policy towards China with great attention. In addition, it expects to benefit from the diversification of production processes of EU companies, implemented as part of the derisking strategy for European business from the EU’s dependence on Chinese supplies. It would also be politically important for India to facilitate legal migration by signing the Migrant and Mobility Partnership Agreement. Poland can improve on concessions for opening its own market to Indian workers and take advantage of the rapidly growing Indian diaspora.

Creating an attractive offer in economic terms may be an easier task. India’s comprehensive modernisation means that there is enormous potential for cooperation. The starting point should be to identify the strengths of Polish companies in the context of India’s needs.

The country is counting on foreign support, especially in sectors such as the green transformation, infrastructure development and connectivity, environmental protection, defence, and digitalization. India’s recent strategic partnerships indicate that the country is strengthening relations with individual partners around one key theme (Water Strategic Partnership with the Netherlands, Energy Transition Strategic Partnership with Italy, Strategic Partnership for Innovation with Czechia, and others), leading to specialisation of cooperation. Poland’s offer should therefore focus on a single, guiding area. Past cooperation indicates that this area could be, for example, information technology, education and training, agri-food processing, or the defence sector. Such a “Skills Development Partnership” could include an offer of scholarships for specialised studies in Poland, investment in education in India, and a joint fund for research and development of modern technologies.

Cooperation with India should also be as broad as possible and include building knowledge and awareness of the new India in Polish society. It is worth increasing the involvement of the Sejm, especially the bilateral parliamentary Friendship Group, renewing contacts with counterparts in the Indian parliament.

It also is important to increase access to regular information from India, which will contribute to a better understanding of the country in Polish society, while greater awareness and more intensive political contacts may induce more Polish businesses to engage in the huge Indian market. The private sector’s willingness to invest in the relationship would encourage a more active diplomatic, economic, and cultural presence.

All this would require not only strengthening the Polish embassy personally and financially but also rethinking the way Poland’s diplomatic representation in this part of the world. It is worth recalling that the Polish embassy in New Delhi represents Poland in a total of seven countries in the region, inhabited by nearly 2 billion people, and thousands of kilometres apart. Poland also has a consulate general in Mumbai and honorary consuls in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. In a minimalist version, it would be helpful to open an embassy in Dhaka (Bangladesh has a population of more than 160 million) and at least one additional consulate in southern India. It would also be worthwhile to have an embassy in Islamabad to take over matters related to Afghanistan in the current circumstances (after the withdrawal of international troops and the Taliban takeover).

A significant increase in the budget of the diplomatic post for public and cultural diplomacy, as well as the budget of the Polish Institute in New Delhi, would expand the possibility of promotional activities and cooperation between expert, journalistic, artistic, or student communities. Definitely, such tools as sending Indian journalists and experts on study visits to Poland should be used more often. This will increase knowledge of Poland in India, which is at a minimal level.[15] It will also foster the creation of Poland-friendly opinion elites. It is also in Poland’s interest to increase knowledge of India among the Polish public, which would be served by sending a permanent correspondent of Polish public media to India.

Conclusions and Recommendations

India’s rise to prominence is one of the primary causes and, at the same time, the result of changes in the international system. The country is emerging as one of the centres of the multipolar world order and one of the engines driving the global economy. The strategic importance and economic opportunities offered by India are prompting a number of Western partners, such as the U.S., the EU, and its Member States, to intensify cooperation with India. Poland should not overlook this historic shift or neglect its relationship with an important international actor in the 21st century.

The last decade in Polish-Indian relations has been lost. While Polish-Indian relations were not gaining sufficient importance, other European countries built much closer political and economic relations with India. In addition to India’s traditional partners in Europe (Germany, France), other EU members (Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Greece), including those from Central Europe (Czechia), have formed strategic partnerships with the country and are strengthening cooperation with it in many dimensions.

The future of these relations and a new opening in relations with India depend, in the first place, on Poland’s strategic decision to define the importance and goals of relations with the country.

The success of the new strategy will depend on a change in thinking about India and a decision to treat it as one of Poland’s most important partners and a global power with a major influence on the world economy and security.

Such a change can only be successful if it comes from the highest levels of government in Poland, given the need to involve various government ministries and institutions—as well as a large budget—in preparing an attractive and mutually beneficial offer of cooperation. Falling in 2024, the 70th anniversary of the establishment of Polish-Indian diplomatic relations presents an opportunity to open a new phase of strategic bilateral relations. Poland can also use the upcoming presidency of the Council of the European Union to strengthen its position, making cooperation with India one of its priorities. Taking advantage of this opportunity, however, requires a combination of political will, preparation of an attractive offer and the allocation of adequate resources for its implementation. Revitalising relations with India could prove to be a useful and non-controversial area of cooperation between the Polish president and government. It could also become an important element of a more ambitious and global Polish foreign policy.

[1] P. Kugiel, D. Wnukowski, “G20 after the New Delhi Summit: India, Developing Countries Claim Success,” PISM Bulletin, No. 132 (2251), 15 September 2023, www.pism.pl.

[2] P. Kugiel, “India’s Ambivalent Stance on Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” PISM Spotlight, No. 35/2022, 3 March 2022, www.pism.pl.

[3] P. Kugiel, “India in the American Vision of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” PISM Bulletin, No. 52 (1123), 6 April 2018, www.pism.pl.

[4] Sejm RP, “Deputy Foreign Minister Wojciech Gerwel’s speech at the conference: Lessons from Russian aggression against Ukraine for Polish foreign policy. Part I: Indo-Pacific and Soft Power,” 21 June 2023.

[5] See more: P. Kugiel, “Polityka Polski wobec Indii od 2004 r.” [“Poland’s Policy Towards India since 2004”], Rocznik Polskiej Polityki Zagranicznej 2019 [Yearbook of Polish Foreign Policy 2019], PISM, Warsaw 2021, pp. 262–273.

[6] Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS), “Szkoły Wyższe i ich finanse w 2010 r.” [“Universities and their finances in 2010”], 2011; “Szkolnictwo wyższe i jego finanse w 2021 r.” [“Universities and their finances in 2021”], 2022.

[7] Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców [Foreigners’ Office], https://migracje.gov.pl.

[8] GUS, “SWAID foreign trade database.”

[9] Indian companies already present in Poland include those in the IT sector, for example: Genpact, Infosys, KPIT-Info systems, HCL, Tata Consultancy Services, Wipro, Zensar Technologies. Companies in other sectors include: UFLEX, Essel Propack, VVF, Berger Paints India, Escorts, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Lambda Therapeutics Research, Lumel SA, and Tata Global Beverages. According to the Indian embassy in Poland, Indian investments are worth $3 billion and IT companies alone have created 10,000 jobs; for more, see: Embassy of India in Warsaw, “India-Poland Relations,” November 2022, www.indianembassywarsaw.gov.in.

[10] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Minister of Foreign Affairs on the principles and objectives of Poland’s foreign policy in 2023,” Warsaw, 13 April 2023, www.gov.pl/web/dyplomacja.

[11] P. Kugiel, “Poland-India: Potential for a Strategic Partnership,” PISM Strategic File, No. 21, May 2012, www.pism.pl.

[12] PISM, “India and Poland: Vistas For Future Partnership. A report from the 3rd Roundtable of the Polish Institute of International Affairs and the Indian Council of World Affairs,” July 2012, p. 5.

[13] For more, see: V. Sakhuja, D.K. Upadhyay, P. Kugiel (eds.), India-Poland Relations in the 21st Century: Vistas for Future Cooperation, KW Publishers, New Delhi, 2014.

[14] See: P. Kugiel, “Indie w procesie reform: szanse dla Polski” [“Modernisation of India: Opportunities for Poland”], PISM Report, February 2018, www.pism.pl.

[15] P. Kugiel, “What Does India Think About Poland?” PISM Policy Paper, No. 15 (63), June 2013, www.pism.pl.

(1).jpg)