The European Union and Mercosur Conclude Talks on Their Partnership Agreement

On 6 December, in Montevideo, the president of the European Commission (EC) and the leaders of four Mercosur members—Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay—announced the conclusion of negotiations on the EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement. Several years of disputes over the trade part of the document, negotiated in June 2019, preceded the decision. The strong opposition in France, the Netherlands, and Poland, among others, to the new version of the agreement—mainly to the scope of agri-food access to the EU market—did not prevent the finalisation of talks but could pose a significant obstacle to the ratification of the agreement in the EU.

.png) Martin Varela Umpierrez / Reuters / Forum

Martin Varela Umpierrez / Reuters / Forum

The decision announced on 6 December means that the EU and Mercosur have reached a political agreement on concluding talks on their Association Agreement held intermittently since 2000. The document has three parts: trade, political dialogue, and sectoral cooperation (migration, digital economy, and human rights, among others), and visibly, it has been renamed to the “EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement”. If adopted, it will create one of the largest free-trade areas in the world, comprising more than 750 million people. The accord is expected to facilitate trade in goods and the development of investment, including by removing most tariff and non-tariff barriers and opening up access to services and government procurement markets. The parties point to the high political significance of the agreement as an essential basis for closer EU cooperation with Mercosur and other Latin American partners. Finalising talks still this year also aimed at sending a strong signal against protectionist tendencies in the world, especially given the fear that the incoming U.S. administration of Donald Trump will exacerbate them.

The Path to the Conclusion of Negotiations

The EU and Mercosur had already announced the end of the talks after consenting to the trade part in June 2019 (the other two parts were accepted a year later). However, the growing discrepancies between the parties made it impossible to proceed with ratification. The main reason was the complaints of some environmental NGOs and EU countries (especially France) that the commitments to sustainable development were insufficient. The EC proposed an additional agreement on this issue, but for Mercosur countries, European protectionism was behind these demands. The introduction of the European Green Deal strategy in 2020 by the EU further complicated the situation because it included increased environmental demands on the Union’s partners. The EU instrument to ban the import of products from areas of illegal deforestation, in particular, was met with a firm rejection by Mercosur. Nonetheless, the countries of the latter bloc have used disagreements to negotiate additional concessions to arrangements agreed upon in 2019. Brazil, for example, won exceptions in the EU’s access to its procurement market.

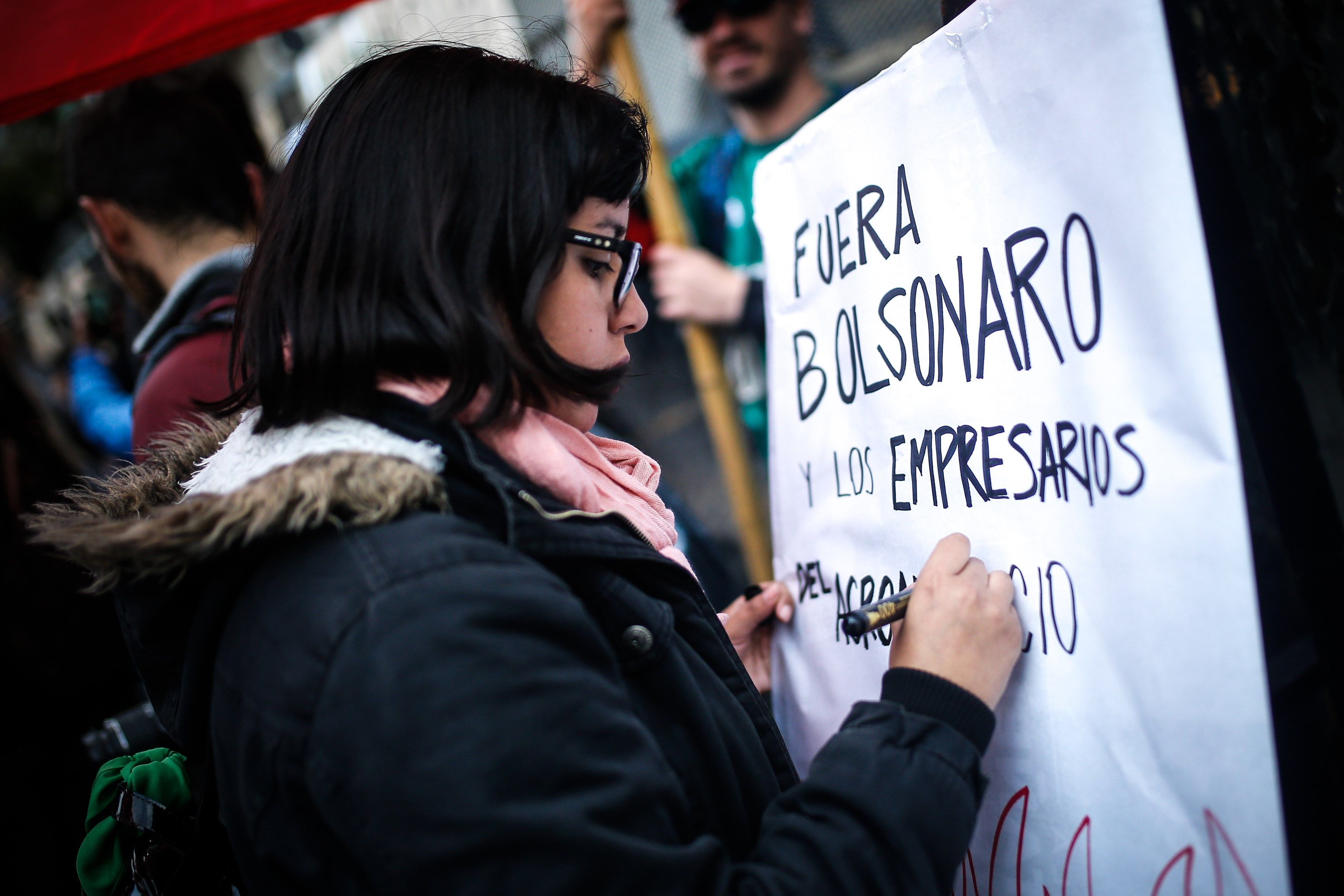

While Mercosur governments have become supportive of the modifications in the agreement, France expressed the loudest opposition to the document’s new version. President, Emmanuel Marcon engaged personally to prevent the conclusion of the talks. For example, he unsuccessfully called for an entirely new agreement during his March visit to Brazil. Last month, the French authorities extensively sought allies for that bid. Countries with similarly large agricultural sectors, Austria, the Netherlands, and Poland, among others, joined France in opposing the deal’s provisions related to the liberalisation of the EU market for food from Mercosur. The EC did not succumb to this pressure and, together with four South American partners, insisted that the agreement was balanced and addressed the concerns raised. The EU’s decision to postpone the entry into force of the EU’s deforestation instrument by one year (30 December 2024 was the previous date) also played a role in convincing the four Mercosur countries to finalise the agreement.

Notably, very little transparency marked the EU-Mercosur Partnership Agreement’s negotiation process and the details of the arrangements. The fragments of the deal negotiated in June 2019 were released successively over several years especially under long-standing pressure from various NGOs. These experiences apparently weighed on the EU’s decision to release the preliminary version of the newly negotiated text as early as 10 December. The document contains several additional commitments on the issue of sustainable development, as evidenced by the indication of the Paris Climate Agreement as the essential element for both blocs. The parties also agreed on strengthened mechanisms against excessive inflows of goods due to market liberalisation and on dispute settlement, as well as on arrangements to facilitate the development of stable supply chains (including critical raw materials for the green transition). They also introduced a review clause to allow amendments—the first such opportunity will be three years after the document’s entry into force.

Prospects for Ratification

In the following months, the agreement will undergo legal verification, which is required to prepare the final text, which will be translated into both blocs' official languages. Once this process is completed, the document will be ready for the formal signature, triggering the ratification process. In Mercosur, this decision will be taken by the four national parliaments. Bolivia, although formally a member of the bloc since July, is undergoing the process of implementing Mercosur norms and is not party to the agreement with the EU.

In the Union, the EC intends to proceed with the trade part separately, which means that a qualified-majority in the Council of the EU and a simple majority in the European Parliament will be required for its adoption. The approval could be hindered in the Council by opposition from France and other countries with strong agri-food sectors, including the Netherlands, Ireland, and Poland. These countries argue that their farmers could be seriously affected by increased imports of cheaper products, including meat, from Mercosur. They also say that agricultural production in the South American bloc is subject to lower food-protection standards and does not meet sustainability principles.

Equally important, however, is the political context. In France, Macron, whose position has weakened over the past year, clearly feared that accepting the agreement would be politically too costly, as it would further antagonise the electorate linked to the agri-food sector. The negative attitude of French or Polish farmers towards the Mercosur agreement is part of their broader rejection of what they consider the excessive requirements imposed by the Green Deal. In Poland, this negative posture also had to do with the adverse experience of increased agricultural imports from Ukraine following Russia’s full-scale invasion of that country. If the attempt to block the agreement in the Council fails, the trade pillar will enter into force provisionally. The other parts will be subject to ratification in the individual EU countries.

While the four Mercosur governments agree on the need to implement the deal, it is uncertain whether this position will translate into support in the national parliaments. In the Argentine Congress, for example, President Javier Milei’s political grouping is in a minority. Similarly, President Lula da Silva’s government in Brazil relies on a broad coalition in Congress, built through various concessions and privileges.

Conclusions

It is unclear when or how long it will take for the final version of the agreement to be ready. Maybe, the parts that in 2019 that passed legal revision and are retained in the new version will no longer need to be re-checked. The smooth completion of these stages could allow the agreement to be formally signed, for example, at the EU and Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) summit in Bogota, planned for the second half of 2025. The ratification process could start in 2026 at the earliest.

The adoption of the EU-Mercosur agreement in the Union will depend primarily on whether the main opponents of the agreement manage to form a blocking minority in the Council. This requires a coalition of at least four Member States with a combined share of at least 35% of the EU population. France, the Netherlands, and Poland could make such an attempt, but convincing Italy is considered crucial to its success.

Poland, which starts its six-month presidency of the Council of the EU on 1 January, is likely to face debates on the Mercosur agreement and, simultaneously, the EC’s potential efforts to convince opponents of the document to support the accord. The Commission may offer some compensatory or protective solutions to alleviate the concerns of the farmers. It will be in Poland’s interest to engage in such discussions. Campaigns against the agreement as the final text is being prepared will be another challenge. The Polish EU presidency may face mounting protests by the agricultural sector and campaigns of NGOs, which argue that the EU-Mercosur accord poses a threat to climate action (for example, by fuelling deforestation for new crops), among other negative outcomes.